When keeping an aquarium for the first time many are confronted with algaes, they cover the glass, plants, decor or even the water itself. Fishes that feed on algaes, known as algivores are often deployed here, sometimes mistakenly.

This I can only assume stems from the idea of a “clean up crew” and an aquarium ‘ecosystem’. The problem here is it is generalising algivores and misunderstanding this dietary niche in general because more then often we all keep algivores because they don’t fit the aesthetic we might not even know. Freshwater ecosystems are very complex and function cannot realistically be replicated in the aquarium.

Who are the algivores?

Algivores come from almost every branch of “fishes” from Cichlidae (Cichlids; Burress, 2016) to Siluriformes (catfishes). Even within these clades there is a wide amount of variation, in cichlids it’s quite obvious but in plecos, Loricariids there is a small number of carnivores and omnivores (Lujan et al., 2012). The actual mechanism of feeding varies a lot and this no doubt influences what algaes they can eat. Even within these groups there is a lot of variation in what algaes they will feed on (Delariva & Agostinho, 2001).

Both of these statements make sense when you buy algivores and they do not feed on some or all of the algaes that are causing an issue in the aquarium. Cyanobacteria makes the best example here, while many fishes do feed on it in the wild (Valencia & Zamudio; Baldo et al., 2019) it’s very evident they do not feed on the cyanobacteria that pests the aquarium, they are likely very different algaes. In many freshwater ecosystems there will be multiple species who feed on algaes and they could only co-exist if there was some partitioning in what algaes they feed on. Most of these fishes also feed on other microbes such as bacteria, protozoa etc. We even see divergent morphology likely based on what and the proportions of the different algaes and those other they feed on. This is where a common misconception comes, many will state that quite a lot of these fishes aren’t algivores because they aren’t ‘cleaning’ your aquarium.

So there is a lot of understanding the individual fishes to know what algaes they will eat and how much.

Another aspect here is the behaviour of algivores is often forgotten as they become more of a purpose then of a focus. Otocinclus, flying foxes (Epalzeorhynchos spp.) and Siamese algae eaters (Crossocheilus spp.) are shoaling and really do benefit from a minimum of 6 as shown here in the wild: https://www.inaturalist.org/taxa/98678-Crossocheilus-reticulatus/browse_photos. For Otocinclus they are shy when housed in small numbers, they are found in their hundreds in the wild. Epalzeorhynchos and Crossocheilus on the other hand in small numbers can become boisterous to each other and other fishes, there is no better example of this then E. bicolor. While for Otocinclus providing a group is rarely an issue for others it could be very limiting on aquarium size and particularly only to feed on one type of algae.

I can’t help but emphasize these fishes have their own requirements and they can be extremely specialized. Just because they feed on algae it does not mean they do not require a specialised environment based on their natural habitat. This is maybe why I see such a high mortality in certain species.

One thing never to forget is how long a fish might live and if it is only to solve an issue that might last a week or a few months you’ll have the fish years or even decades. Particularly catfishes, Loricariids/plecos, who are exceptionally long lived as often discussed in conversations:

- https://www.planetcatfish.com/forum/viewtopic.php?t=6919#:~:text=I’d%20expect%2010%20years,to%20be%20long%20lived%20fishes.

- https://www.planetcatfish.com/general/general.php?article_id=441

Rehoming for some of these fishes can provide a particular challenge.

So what are the commonly recommended algivores:

Otocinclus spp.

Common name: Dwarf pleco, Oto

Locality: Widespread across South America (GBIF Backbone Taxonomy, 2023; Fricke et al., 2023)

Size: 16.5-43.8mm Standard Length (SL; Shaefer, 1997)

Comments: A small, shoaling (Axenrot & Kullander, 2003) genera found in clear, sandy waters with plenty of vegetation (Reis, 2004). This genus specialises in the finer algaes and other microbes growing on the variety of surfaces (Axenrot & Kullander, 2003). Otocinclus as a name has been used as a common name to refer to many other Hypoptopominae not all that stay that small, some such as Hypoptopoma incognitum at 9.4cm SL (Aquino & Schaefer, 2010). These other Hypoptopominae (The subfamily of Loricariidae that contains Otocinclus) are still just as social and some can be much more challenging to feed and sustain in captivity. I personally find particularly Rhinotocinclus and Nannoptopoma really suffer with the majority of ‘algae’ wafers where there isn’t a high amount of algae’s in the ingredient list. Otocinclus definitely do deal with the algae in an aquarium but not all such as black beard or cyanobacteria, after the algae is gone though they will need a more specialist algae based diet.

Ancistrus sp. ‘Common bristlenose’

Common name: BN, bristlenose pleco.

Locality: Unknown.

Size: 12-20cm SL, very variable.

Comments: This is a domestic species you’ll often see associated with Ancistrus cirrhosus or Ancistrus dolichopterus but it is related to neither of these species. As this species has been bred into many different variants from albino, super red, snow white to green dragon, there is additionally a lot of variation in size. It also makes any husbandry a lot more unpredictable as we neither know what the original species is nor can we really say how domestication has effected them. Unlike a few other Ancistrus this species is territorial and can take on any similarly shaped fishes if they enter their space, unlike many misconceptions this is regardless of sex. These do feed on algae but I can’t say they will deal with any on plants, nor black beard algae, cyanobacteria or most diatoms. Given how long these fishes can live and their size, certainly a consideration for any tank and they still have their own requirements.

Epalzeorhynchos, Crossocheilus and Tariqilabeo

Common name: Sharks, algae eaters and flying foxes.

Locality: East Asia.

Size: 12.46cm SL (Ciccotto et al., 2017) although individuals potentially grow up to 15cm SL in captivity.

Comments: As mentioned above generally social fishes who are boisterous with age in low numbers. They are brilliant in the right situation but temperatures definitely have to be considered for example the fishnet flying fox, Crossocheilus reticulatus who inhabits rapids and much cooler temperatures then generally expected. Certainly underrated fishes where they are almost never kept as the focus of an aquarium. Often noted to feed on black beard algaes but I’m not sure they are that rapid at it.

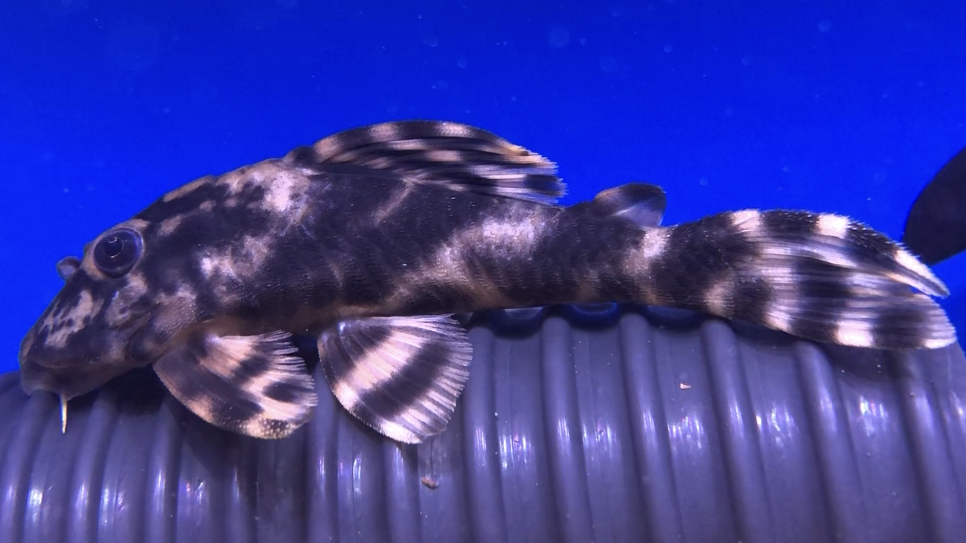

There are soo many fishes recommended and this changes with time such as the hillstream loaches, Gastromyzontidae who inhabit the rocky rapids of Asia but I might ask to look at these fishes in the wild and how specialised they are: https://uk.inaturalist.org/taxa/1032183-Gastromyzontidae/browse_photos

The actual problem, algaes

It is no doubt true that algaes can release toxins, these algaes have not been seen in the freshwater aquarium. Therefore, there is no real harm to algaes themselves excluding blocking filter inlets, outlets and sponges. More then anything algaes are a symptom of a variety of nutrients or conditions, some of them just might be an aquarium stabilising over the years.

Aquariums do have an ecosystem when it comes to microbes and with time the composition of these microbes will change. Aquariums don’t seem to really stabilise for years, obviously this likely wont have any scientific research behind it but if we look at natural ecosystems succession is a well known process. Succession is where the organisms change over time, while species diversity increases over time towards the end it then decreases. There is no same end goal to succession as it varies on so many factors and succession can be halted by certain species or environmental factors.

Of course the best method in the short term is likely really manually removing algae, this will likely effect this succession as removing the microbial populations that are competing with the algaes. Having worked in stores I use a variety of tools (ensure they are used for nothing else):

- Scouring pad: Be careful on acrylic but this is great for most algaes and with a bit of hard work even diatoms.

- Toothbrush: This is for the corners but can even work on decor. It can make a good attempt on blackbeard algae. Do not use too harshly on the corners as can damage and remove silicone.

- Stanley blade: Definitely very sharp so be careful! Used wrong it can scratch glass and acrylic. Once you work out the right angle it’s great for removing any algaes such as diatoms and blackbeard on flat surfaces.

- Filter Floss: Sometimes can be useful to clean large areas of soft algae, it can scratch the glass if catches sand granules but an easy thing to grab.

I personally do not recommend any of the magnetic algae cleaners due to the fact they tend to only remove the softest algaes and can easily catch sand, scratching the glass. T

Algaes themselves would deserve their own article but because of the polyphyletic (pick and mix) nature of the term between many very diverse groups of organisms, just because they are photosynthetic they aren’t simple.

I would treat algaes for mature aquariums particularly any sudden change in algaes present as biological indicators of nutrients, often ones we can’t or rarely test for.

The relationship between nutrients and algaes

Algal growth is inherently connected to nutrient composition. Unlike plants algaes can reproduce at a much more rapid rate taking advantage of any nutrients, the amount of algaes is usually connected to higher nitrate (Taziki et al., 2015) and phosphate levels (Fried et al., 2003). This makes sense as while a lot of rivers contain algaes which can contribute to the majority of the trophic interactions from photosynthesis, naturally rivers and lakes are oligotrophic (Lewis et al., 2001). Some of this nutrients we can’t help like nitrates out of the tap but when simply water changes which will benefit the health of the fish, what is the harm of that 30-60 minutes a week? Surely even a hamster, snake etc. takes more time. In another article I will probably discuss how to deal with when the source water is causing issues other then my article on RO.

Some sources of nutrients are easily forgotten, from certain botanicals to certain substrates. If it is the substrate usually it’ll be there from the beginning but adding certain botanicals like palms it’ll appear later on.

Conclusion

Algaes themselves are harmless and I think at some point we need to see them for what they are, maybe more interesting indicators.

References:

Aquino, A. E., & Schaefer, S. A. (2010). Systematics of the genus Hypoptopoma Günther, 1868 (Siluriformes, Loricariidae). Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History, 2010(336), 1-110.

Axenrot, T. E., & Kullander, S. O. (2003). Corydoras diphyes (Siluriformes: Callichthyidae) and Otocinclus mimulus (Siluriformes: Loricariidae), two new species of catfishes from Paraguay, a case of mimetic association. Ichthyological Exploration of Freshwaters, 14(3), 249-272.

Baldo, L., Riera, J. L., Salzburger, W., & Barluenga, M. (2019). Phylogeography and ecological niche shape the cichlid fish gut microbiota in Central American and African Lakes. Frontiers in microbiology, 10, 2372.

Burress, E. D. (2016). Ecological diversification associated with the pharyngeal jaw diversity of Neotropical cichlid fishes. Journal of Animal Ecology, 85(1), 302-313.

Ciccotto, P. J., Pfeiffer, J. M., & Page, L. M. (2017). Revision of the cyprinid genus Crossocheilus (Tribe Labeonini) with description of a new species. Copeia, 105(2), 269-292.

Delariva, R. L., & Agostinho, A. A. (2001). Relationship between morphology and diets of six neotropical loricariids. Journal of Fish Biology, 58(3), 832-847.

Fricke, R., Eschmeyer, W. N. & Van der Laan, R. 2023. ESCHMEYER’S CATALOG OF FISHES: GENERA, SPECIES, REFERENCES. (http://researcharchive.calacademy.org/research/ichthyology/catalog/fishcatmain.asp).

Fried, S., Mackie, B., & Nothwehr, E. (2003). Nitrate and phosphate levels positively affect the growth of algae species found in Perry Pond. Tillers, 4, 21-24.

Lewis Jr, W. M., Hamilton, S. K., Rodríguez, M. A., Saunders III, J. F., & Lasi, M. A. (2001). Foodweb analysis of the Orinoco floodplain based on production estimates and stable isotope data. Journal of the North American Benthological Society, 20(2), 241-254.

Lujan, N. K., Winemiller, K. O., & Armbruster, J. W. (2012). Trophic diversity in the evolution and community assembly of loricariid catfishes. BMC Evolutionary Biology, 12(1), 1-13.

Otocinclus Cope, 1871 in GBIF Secretariat. GBIF Backbone Taxonomy. Checklist dataset https://doi.org/10.15468/39omei accessed via GBIF.org on 2023-10-24.

Reis, R. E. (2004). Otocinclus cocama, a new uniquely colored loricariid catfish from Peru (Teleostei: Siluriformes), with comments on the impact of taxonomic revisions to the discovery of new taxa. Neotropical Ichthyology, 2, 109-115.

Schaefer, S. A. (1997). The Neotropical cascudinhos: systematics and biogeography of the Otocinclus catfishes (Siluriformes: Loricariidae). Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia, 148, 1-120.

Taziki, M., Ahmadzadeh, H., Murry, M. A., & Lyon, S. R. (2015). Nitrate and nitrite removal from wastewater using algae. Current Biotechnology, 4(4), 426-440.

Valencia, C. R., & Zamudio, H. (2007). Dieta y reproducción de Lasiancistrus caucanus (Pisces: Loricariidae) en la cuenca del río La Vieja, Alto Cauca, Colombia. Revista del Museo Argentino de Ciencias Naturales nueva serie, 9(2), 95-101.