While the majority of Loricariids are algivores/detritivores (Lujan et al., 2012), there is a number of those who are carnivorous and even less likely specialise in molluscs.

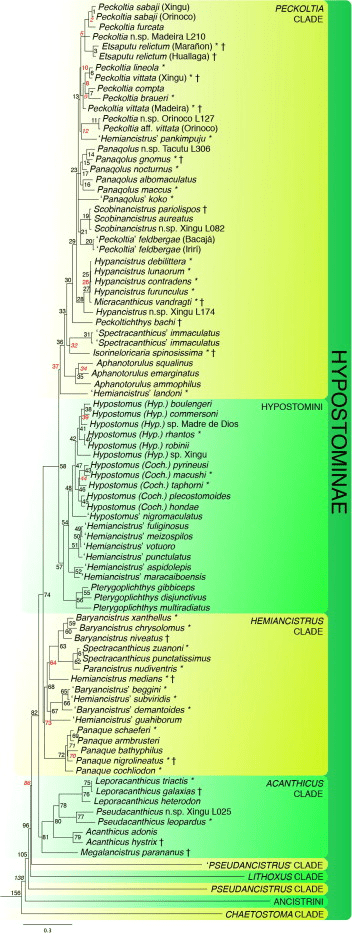

Scobinancistrus and Leporacanthicus are both genera in the subfamily Hypostominae of the Siluriforme (catfish) family, Loricariidae. Scobinancistrus is nested within the Peckoltia group while Leporacanthicus places within the Acanthicus group (Fig 2). As a result these two species are not closely related at all, making the molluscivorous dietary niche convergent.

Both genera are reasonably small in size, Leporacanthicus contains four described species: L. galaxias (Galaxy/vampire pleco/L007/L240), L. joselimai (Sultan pleco/L264), L. heterodon (Golden vampire pleco) and L. triactus (Three becon pleco/L091); Scobinancistrus contains three described species: S. auratus (Sunshine pleco/L014), S. pariolispos (Golden cloud pleco/L133) and S. raonii (L082). There are multiple undescribed species or variant’s in both genera. Species descriptions are included in the reference list.

Neither of these genera are particularly small in size particularly Scobinancistrus where both S. pariolispos, S. auratus and the undescribed species grow to 30cm SL, S. raonii being an exception at 22cm SL (Chaves et al., 2023). On the other hand Leporacanthicus while the Acanthicus group represents the largest species is generally around 24cm SL (Collins et al., 2015) with the exception of Leporacanthicus joselimai at around 15cm SL (Isbrücker & Nijssen, 1989). So these are not the smallest of fishes but generally the scientific literature includes much smaller sizes then some of the images of fishes obtained from the wild.

When we look at habitats for this clade it is generally always rocky with little to no macrophyte plants, these fishes enjoy a good current (Chaves et al., 2023; Isbrücker & Nijssen, 1989; https://amazonas.dk/index.php/articles/brasilien-rio-xingu). This is partially a clue to why their morphology is the way it is. Particularly those Rio Xingu species e.g. Scobinancistrus auratus, S. raonii and Leporacanthicus heterodon will not experience temperatures below 28c (Rofrigues-Filho et al., 2015).

While juveniles are not noted to be a particular issue unlike the majority of the Acanthicus clade both can be particularly territorial with age. I have a clear memory of a Leporacanthicus breeder explaining how a pair couldn’t be housed with other Loricariids due to the level of aggression. In a larger aquarium with plenty of caves and decor to break up the tank could work but this has to be taken into consideration for the future.

Dietary niche

Both of these genera have very specialist jaws, they are particularly agile to move around or into a food item as displayed in figure 3. This mobility of the soft oral suction cup-like mouth is to more of an extreme then other carnivores; Pseudacanthicus who is much more general as a carnivore.

Leporacanthicus goes a little more further with a particularly large, fleshy with many particularly large unculi.

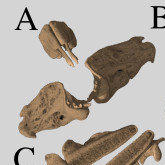

If anything talks about diets so much, it is the skeletal anatomy and the jaws (Fig 5). These two genera have very robust jaws but other Loricariids particularly Hypostominae have this, what separates Scobinancistrus and Leporacanthicus is the area around the tooth cup. It is extremely elongate downwards, protruding but unlike other Loricariids it is also very limited for teeth (Fig 5).

The teeth are very few and sparse, which correlates with carnivory (Lujan et al., 2012). These teeth being strong, maybe due to colouration maybe mineralised and, more then anything long.

Their diet

These fish are adapted for reaching into something so……..molluscs……..

The interesting thing about diets is for quite a lot of species we don’t entirely know what they eat. Gut analysis is still the most common method of analysing animal diets but that only shows a snapshot of what is in their gut at that time but ignores seasonal variance or digestion. Hence Panaque being a particular curiosity, few organisms can digest wood were studied further but others it’s not looked further. Often with fishes only a small number of individuals are used which can limit it further. When thinking functionally half of diet is what they eat the rest is where they eat, like it’s fine to eat invertebrates, many animals do but to extract it from an object is another, you can’t compare their morphology.

The suggestion of these fishes feeding on molluscs is not old (Black & Armbruster 2022), other groups e.g. fishes are confirmed to feed on molluscs but morphologically nothing similar. Morphology doesn’t mean molluscs are not their diet as molluscs can be in difficult to reach areas.

The description of Scobinancistrus raonii was the most detailed of their diets inferring the use of invertebrates, algaes and porferia (I know an invertebrate; Chaves et al., 2023). Porferia is not a rare mention in the scientific literature as a Loricariid diet as featuring in the diet of Megalancistrus aculeatus but based on dietary analysis (Delariva & Agostinho, 2001). Sponges are a discussion that would need analysing further, Professor Donovan P. German, a scientist specialising in fishes diets discusses that previous fishes that specialise in sponges do so similar to Panaque, they break down the sponges in search of things they can digest. So I will illude suggestions they can digest sponges, either way not a viable diet in captivity as sponges take so long to grow.

Personal experience only hold up so much ground but I have experienced both take particular interest in molluscs and extracting them from their shells, unlike other taxa they cannot crush those shells. Their jaws and teeth even just suggest how they cannot crush, look at your own teeth, your crushing teeth are rounder and shorter.

We don’t really know if they do eat molluscs, the bodies of molluscs wont appear on gut analysis as easily processed. I don’t know yet enough about isotope analysis to test other methods. But if they show the interest it’s something to explore.

The other avenue is these long jaws and teeth are for extracting things from the cracks and crevices in wood.

Either way though we don’t have the captive diets to really cater carnivory that well yet so no harm in the snails but look at a diet that is based on invertebrates. They show an interest in molluscs so those without the trapdoor would be amazing.

In Loricariidae there is the new frontier in diets, places to explore and understand. We do not know yet so worth looking further. We are miles from the answer in what they really digest and eat.

References:

Black, C. R., & Armbruster, J. W. (2022). Chew on this: Oral jaw shape is not correlated with diet type in loricariid catfishes. Plos one, 17(11), e0277102.

Collins, R. A., Ribeiro, E. D., Machado, V. N., Hrbek, T., & Farias, I. P. (2015). A preliminary inventory of the catfishes of the lower Rio Nhamundá, Brazil (Ostariophysi, Siluriformes). Biodiversity Data Journal, (3).

Delariva, R. L., & Agostinho, A. A. (2001). Relationship between morphology and diets of six neotropical loricariids. Journal of Fish Biology, 58(3), 832-847.

Lujan, N. K., Armbruster, J. W., Lovejoy, N. R., & López-Fernández, H. (2015). Multilocus molecular phylogeny of the suckermouth armored catfishes (Siluriformes: Loricariidae) with a focus on subfamily Hypostominae. Molecular phylogenetics and evolution, 82, 269-288.

Lujan, N. K., Winemiller, K. O., & Armbruster, J. W. (2012). Trophic diversity in the evolution and community assembly of loricariid catfishes. BMC Evolutionary Biology, 12(1), 1-13.

Rios-Villamizar, E. A., Piedade, M. T. F., Da Costa, J. G., Adeney, J. M. and Junk, W. J. (2013). Chemistry of different Amazonian water types for river classification: A preliminary review. Water and Society 2013, 178.

Species descriptions:

Burgess, W. E. (1994). Scobinancistrus aureatus, a new species of Loricariid Catfish from the Rio Xingu (Loricariidae: Ancistrinae). TFH Magazine. 43(1):236–42.

Chaves, M. S., Oliveira, R. R., Gonçalves, A. P., Sousa, L. M., & Py-Daniel, L. H. R. (2023). A new species of armored catfish of the genus Scobinancistrus (Loricariidae: Hypostominae) from the Xingu River basin, Brazil. Neotropical Ichthyology, 21, e230038.

Isbrücker I. J. H. and Nijssen H. (1989). Diagnose dreier neuer Harnischwelsgattungen mit fünf neuen Arten aus Brasilien (Pisces, Siluriformes, Loricariidae). DATZ. 42(9):541–47

Isbrucker, I. J., Nijssen, H., & Nico, L. G. (1992). Leporacanthicus triactis, a new loricariid fish from upper Orinoco River tributaries in Venezuela and Colombia (Pisces, Siluriformes, Loricariidae). Die Aquarien-und Terrarienzeitschrift (DATZ), 46(1), 30-34.

Pingback: Premixed foods for plecos (Loricariids) and other rasping fishes. | The Scientific Fishkeeper

Pingback: What to feed your pleco when they wont eat. | The Scientific Fishkeeper

Pingback: Pleco’s and Whiptail Catfishes, the Beginners Guide to Loricariid catfishes. | The Scientific Fishkeeper