There are few fishes that really catch the eye as much as the order of true knifefishes, Gymnotiformes. Sometimes confused with some Asian and African species from the group Notopteridae which is within the family Osteoglossiformes, also within that group is the arowana. Gymnotiformes are restricted to South America with the closest relatives being Siluriforme (catfishes) and the tetras (Characiformes) both groups who have a much wider distribution.

Gymnotiforme contains 6 families, 36 genera and 272 species (Fricke et al., 2024). Of these species only one is a frequent import, Apternotus albifrons with the common name black ghost knifefish. Other species do appear in the trade but much less frequently otherwise this article would be more specific.

Morphology

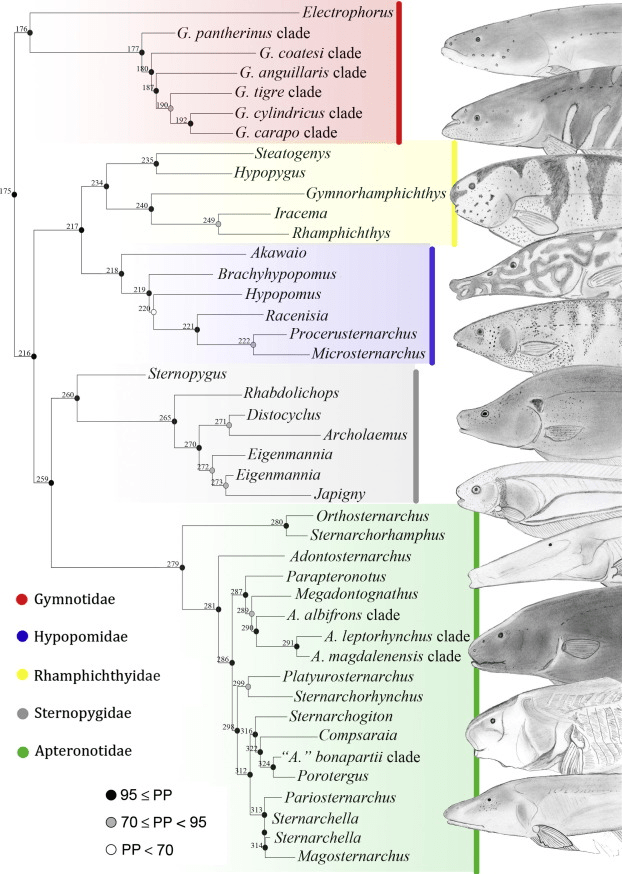

The order is generally identified by an eel (anguilliform) shaped body, a large anal fin that extends across the majority of the fishes abdomen, no dorsal/adipose/pelvic fins and; a caudal fin might be present but reduced (Tagliacollo et al., 2016).

The largest Gymnotiformes are in the genus Electrophorus, electric eels of which comprises 4 species, with evidence of individuals reaching over 120cm TL (de Santana et al., 2019). While the smallest might be Hypopygus minissimus at 6.4cm SL (de Santana & Crampton, 2011).

The largest amount of diversity of this family would be in the head shape, there are many with shorter heads and extremely gape limited, others with elongated jaws, some with wide jaws and quite a few with a long snout like mouth. This likely reflects their diet, while all are carnivores there is a wide range of different prey various genera will specialize in (Albert & Crampton, 2005; Ford et al., 2022).

Colouration is extremely variable although they lack any vivid colours the markings differ based likely on the environment. My personal favorite’s for colouration are the various striped members of the genus Gymnotus.

The complexity of dietary specialization

As mentioned earlier Gymnotiformes display a wide diversity of jaw and mouth shapes, some are likely more generalists and others much more specialized. A large number of genus that occur on the rare occasion tend to be these specialists.

Gymnotiformes are all carnivores and many invertivores/insectivores (Gonçalves-Silva et al., 2022; Giora et al., 2014). Some feed on particularly small food items for their relative body size. Lundberg & Mago-Leccia (1986) displayed many species feeding exclusively on plankton regardless of their body size of 8-14cm SL in some of these species. This planktivorous diet is found in many of these long nosed and gape limited species (Giora et al., 2014; Lundberg & Mago-Leccia, 1986). These species simply cannot feed on larger food items and seems to display preferences additionally on the food item. I can only recommend for these trying many different frozen and live foods in a tank with nothing that can compete but even if feeding they can be a challenge and I do not recommend. Feeding these species takes time and requires space for culturing live food, they are probably best species only.

There are genera that do work within captivity although very few. Apternotus albifrons and A. leptorhynchus the brown and black ghost knifefish, not to be confused with a Notopteridae the brown knifefish, Xenomystus nigri from Africa. These have larger mouths that extend so can even feed on tetra but due to their adult size of 30cm SL (Mucha et al., 2021) but in the aquarium some suggest 50cm. This makes them a bit of an undertaking, so the social X. nigri might be a better choice at about 11-15cm SL (Golubtsov & Darkov, 2008). X. nigri has a more extreme arched back, solid grey/black/brown colouring and the anal fin connects directly to the caudal fin. Gymnotus is the other appropriate genus to the aquarium, it is variable in size from around 15cm for Gymnotus javari to 60cm for Gymnotus carapo (Craig et al., 2019). The mouth of Gymnotus doesn’t open as wide as Apternotus and is generally a more shy fish, so would need much less competition. Gymnotus does provide a problem as while there is such a range in size the species provide issues for the fishkeeper in identifying, often small differences. G. carapo vs G. javari is at least easier, the former has the most vivid colouring with distinct black and white wide stripes maybe with spots but I think is slightly more arched in the back.

Feeding these two genera then if they can be fed on fry foods is the best for the range of vitamins, minerals and general nutrition. Otherwise Gymnotus can be a little more specialized requiring freeze dried, frozen or live foods but are at least generalists. For Gymnotus a range of frozen and freeze dried foods is a must but on top look around for different live foods appropriate for their mouth size, I feed my G. javari earthworms in terms of live foods to avoid those I cannot culture.

This is not typically a genus for the majority of tanks but they are illusive fishes regardless so take the real pet rock fish enthusiast. Gymnotus and two of the Apternotus would be the best choice for the majority of people.

Habitat and setup

Gymnotiforme’s are illusive fishes, they will spend most of their time hiding whether it be in caves or some species will bury themselves in the sand (Escamilla-Pinilla et al., 2019). Therefore a wide diversity of different hiding spaces are a must for these fishes, while some might suggest glass caves given these fishes have eyes they can detect light and dark and would feel safer in a dark area.

There is quite the diversity in habitats but the majority of specialists are maybe more riparian/marginal species. Many of these smaller specialists species would enjoy a habitat with many botanicals or plants (Crampton, 2016) but this might not be possible due to trapping food although if lucky it could encourage smaller invertebrates like ostracods. While others exploit deep channels of water (Evans et al., 2019) therefore without these botanicals or leaf litter but large wood/and or rocks would be present. These found in areas of high botanicals it would be worth considering that they inhabit areas of very low pH and conductivity (Bichuette & Trajano, 2015). Of the larger more adaptable species inhabit a wider range of habitats, Gymnotus is shown to prefer a rocky habitat although can be found at surprisingly high pH (7.6-7.8) and conductivities of (170-190 uScm-1) according to Richer-de-Forges et al. (2009) .

Sociality

As with many fishes there are social Gymnotiformes and those less so. Many are social although as a curiosity Apternotus females are shown to be social whereas the males are ill-tolerant of other individuals (Henninger et al., 2020; Dunlap & Larkins‐Ford, 2003). Similarly Gymnotus javari are suggested to be social whereas the majority of the genus doesn’t tolerate other individuals (Westby & Box 1970; https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OMRu_YUBE34). The more specialist species seem to be so much more social and even then many fishes seem to learn to feed from each other.

Identification

Outside of the two groups I recommend most the issue has to be identification and I have given clues how to identify a few. There is a lot more diversity and this makes this group tricky. It is certainly a taxa delving into the scientific literature outside of Apternotus where the black and brown ghost knives are obvious. So this does mean Gymnotus is a little risky with obtaining a species that can grow much larger.

Conclusion

To write a whole article about Gymnotiformes without mentioning their amazing electrical abilities, well that doesn’t entirely concern us as fishkeepers with the exception of Electrophorus, the electric eel of which needs an article of it’s own. These are also likely very intelligent fishes who would benefit from a tank that has a variety of decor and landscapes.

References:

Albert, J. S., & Crampton, W. G. (2005). Diversity and phylogeny of Neotropical electric fishes (Gymnotiformes). In Electroreception (pp. 360-409). New York, NY: Springer New York.

Bichuette, M. E., & Trajano, E. (2015). Population density and habitat of an endangered cave fish Eigenmannia vicentespelaea Triques, 1996 (Ostariophysi: Gymnotiformes) from a karst area in central Brazil. Neotropical Ichthyology, 13, 113-122.

Craig, J. M., Kim, L. Y., Tagliacollo, V. A., & Albert, J. S. (2019). Phylogenetic revision of Gymnotidae (Teleostei: Gymnotiformes), with descriptions of six subgenera. PLoS One, 14(11), e0224599.

Crampton, W. G., De Santana, C. D., Waddell, J. C., & Lovejoy, N. R. (2016). Phylogenetic systematics, biogeography, and ecology of the electric fish genus Brachyhypopomus (Ostariophysi: Gymnotiformes). PLoS One, 11(10), e0161680.

de Santana, C. D., & Crampton, W. G. (2011). Phylogenetic interrelationships, taxonomy, and reductive evolution in the Neotropical electric fish genus Hypopygus (Teleostei, Ostariophysi, Gymnotiformes). Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, 163(4), 1096-1156.

de Santana, C. D., Crampton, W. G., Dillman, C. B., Frederico, R. G., Sabaj, M. H., Covain, R., … & Wosiacki, W. B. (2019). Unexpected species diversity in electric eels with a description of the strongest living bioelectricity generator. Nature communications, 10(1), 1-10.

Dunlap, K. D., & Larkins‐Ford, J. (2003). Production of aggressive electrocommunication signals to progressively realistic social stimuli in male Apteronotus leptorhynchus. Ethology, 109(3), 243-258.

Escamilla-Pinilla, C., Mojica, J. I., & Molina, J. (2019). Spatial and temporal distribution of Gymnorhamphichthys rondoni (Gymnotiformes: Rhamphichthyidae) in a long-term study of an Amazonian terra firme stream, Leticia-Colombia. Neotropical Ichthyology, 17, e190006.

Evans, K. M., Kim, L. Y., Schubert, B. A., & Albert, J. S. (2019). Ecomorphology of neotropical electric fishes: an integrative approach to testing the relationships between form, function, and trophic ecology. Integrative Organismal Biology, 1(1), obz015.

Ford, K. L., Bernt, M. J., Summers, A. P., & Albert, J. S. (2022). Mosaic evolution of craniofacial morphologies in ghost electric fishes (Gymnotiformes: Apteronotidae). Ichthyology & Herpetology, 110(2), 315-326.

Fricke, R., Eschmeyer, W. N. & Van der Laan, R. 2024. ESCHMEYER’S CATALOG OF FISHES: GENERA, SPECIES, REFERENCES. (http://researcharchive.calacademy.org/research/ichthyology/catalog/fishcatmain.asp).

Giora, J., Tarasconi, H. M., & Fialho, C. B. (2014). Reproduction and feeding of the electric fish Brachyhypopomus gauderio (Gymnotiformes: Hypopomidae) and the discussion of a life history pattern for gymnotiforms from high latitudes. PloS one, 9(9), e106515.

Golubtsov, A. S., & Darkov, A. A. (2008). A review of fish diversity in the main drainage systems of Ethiopia based on the data obtained by 2008. In Ecological and faunistic studies in Ethiopia, Proceedings of jubilee meeting “Joint Ethio-Russian Biological Expedition (Vol. 20, pp. 69-102). Moscow: KMK Scientific Press.

Gonçalves-Silva, M., Luduvice, J. S., Gomes, M. V. T., Rosa, D. C., & Brito, M. F. (2022). Influence of ontogenetic stages and seasonality on the diet of the longtail knifefish Sternopygus macrurus (Gymnotiformes, Sternopygidae) in a large Neotropical river. Studies on Neotropical Fauna and Environment, 57(1), 11-17.

Henninger, J., Krahe, R., Sinz, F., & Benda, J. (2020). Tracking activity patterns of a multispecies community of gymnotiform weakly electric fish in their neotropical habitat without tagging. Journal of Experimental Biology, 223(3), jeb206342.

Lundberg, J. G., & Mago-Leccia, F. (1986). A review of Rhabdolichops (Gymnotiformes, Sternopygidae), a genus of South American freshwater fishes, with descriptions of four new species. Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia, 53-85.

Mucha, S., Chapman, L. J., & Krahe, R. (2021). The weakly electric fish, Apteronotus albifrons, actively avoids experimentally induced hypoxia. Journal of Comparative Physiology A, 207(3), 369-379.

Richer-de-Forges, M. M., Crampton, W. G., & Albert, J. S. (2009). A new species of Gymnotus (Gymnotiformes, Gymnotidae) from Uruguay: description of a model species in neurophysiological research. Copeia, 2009(3), 538-544.

Tagliacollo, V. A., Bernt, M. J., Craig, J. M., Oliveira, C., & Albert, J. S. (2016). Model-based total evidence phylogeny of Neotropical electric knifefishes (Teleostei, Gymnotiformes). Molecular phylogenetics and evolution, 95, 20-33.

Westby, G. M., & Box, H. O. (1970). Prediction of dominance in social groups of the electric fish, Gymnotus carapo. Psychonomic Science, 21(3), 181-183.