Banjo catfishes, Aspredinidae are a frequent catfish family that appears within the aquarium hobby although the majority will have seen and kept individuals from a single genus, Bunocephalus. Little seems known about the other Aspredinidae that rarely circulate the hobby.

Taxonomy and Phylogenetics

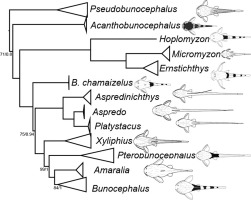

Aspredinidae is comprised of 13 genera and 49 species (Fricke et al., 2024), so it is a relatively small group of catfishes. As above Bunocephalus is the most commonly seen genus although Platystacus cotylephorus, Pterobunocephalus, Pseudobunocephalus and Amaralia are seen in the trade. The majority of these represent the smaller members of the family growing to around a maximum of 6-7cm SL, although Platystacus cotylephorus being the exception growing closer to 30cm SL similar to it’s sister genus, Aspredo (Carvalho et al., 2018; Fig 1). At one point Platystacus cotlyphorus was actually placed in Aspredo and you might see that in museum collections. I am unclear as to whether Aspredo does enter the aquarium trade.

Between these groups there is a clear morphological trend, although identification to species level in some can be particularly tricky.

This group is exclusive to South America but particularly widespread, curiously much of their morphology seems conserved across the group and given the limited species number it infers to me they are quite generalist and adaptable. The adaptability is certainly evident for anyone who has kept Bunocephalus.

Platystacus cotylephorus is one of the most elongate members of the family, it has a large caudal peduncle with an elongate anal fin. This anal fin extending from the anus to close to the caudal fin is rather distinctive but is also found in Aspredo aspredo. In my experience, it seems to help with swimming in the water column and frequent activity, something I also saw in Pterobunocephalus sp. ‘Peru white’ (Fig 2). Unlike Bunocephalus these fishes are a lot more ventrally-dorsally compressed. Their pectoral fin spines are much stronger and more heavily serrated.

These are largely bottom dwelling fishes with inferior mouths, facing downwards and that is largely where they feed. Don’t be mistaken Platystacus will enter the water column occasionally, I find mostly when introduced to a new tank, they seem to exploit the current but unlike a typical fish are not the best at directing themselves. They use their larger pectorals and pelvic fins to glide with the anal fin like a stern to help guide themselves. When moving around the bottom they use that anal fin and eel shape much more. I can imagine in the wild they are much more adapted to leaf litter.

Many species of Aspredinidae display a wide diversity of colouration within species and it doesn’t seem to be due to locality. Platystacus cotylephorus being no exception but generally there are lighter more beige individuals and darker mahogany wood individuals, some have more markings then others.

Strangely there is little literature on the species regardless of it’s fascinating biology.

Etymology

Platys refers to the flat shape at the anterior of the fish and acus refers to the needle like posterior of the fish. Cotylephorus is even more interesting cotyla refers to a cup and phorus to bear. This scientific name is perfect, it describes the shape of the fish, the species epithet meaning bearing cups, these fishes have eggs attached via stalks to the abdomen of the fish (https://etyfish.org/siluriformes10/).

Diet

These are carnivores, pretty clear likely carnivores given their morphology, they do seem to lack oral teeth although I would not be surprised if they had substantial pharyngeal jaws. They respond with a reasonable speed to any of those invertebrate based food items and do not seem fussy.

The main issue with Platystacus cotylephorus and this goes for other Aspredinidae it seems that their abdominal cavity is much more restricted then Bunocephalus or in fact other catfishes. They cannot handle certain food items or high volumes, it seems to cause bloat that can be fatal. This means they really shouldn’t be in a tank where they can gorge themselves to death but also be careful to avoid too much fish meal based diets. I keep mine with Baryancistrus spp. right now which means I can control how much they have while the Baryancistrus have an awful lot of algaes.

So while for carnivorous fish I think there is a whole range they can be fed, for Platystacus cotylephorus I’d step back and think. If that abdomen is extended and the females do produce a lot of eggs, then it is best to reduce feeding for the time being.

Vocalization through stridulating

I’m surprised this isn’t talked about as much in the hobby. Many Aspredinidae or catfishes in general are capable of making sounds, sometimes it’s from the swim bladder but in this case it’s from those pectoral fins. Platystacus cotylephorus seem to make a range of sounds but it’s difficult to know what they are for. If handled and usually before they draw blood there is a higher pitch sound. I have caught a male during water being emptied for a water change making a cracking/clapping like sound, a much lower pitch sound.

Sounds aren’t frequently heard but it does happen.

Shedding skin

I’m not sure how clear it is as to why they do this, it is probably and possibly to a source of irritation. Unlike many other fishes it is not just the slime coat but a thin layer of skins. I find sometimes it seems to be done frequently but all I can say is these fishes are capable of doing it.

Sexing

This is assumed by the dorsal fin, males having dorsal extensions that can develop rapidly while the fish matures. Females have a much more rounded dorsal fin. Other then that I certainly would say there is little other difference unless that female is full of eggs and can have a slight yellow tinge to the abdomen.

Spawning

As far as I know Platystacus cotylephorus has never been spawned in captivity. Females carry the eggs on stalks on their abdomens and individuals have been imported in this state. It is not just Platystacus who does this but many members of Aspredinidae. These stalks don’t just function as attachment but somewhat function as a placenta for the developing embryo’s (Wetzel et al., 1997). I would be curious if there is any correlation between activity levels and this reproductive method between species.

Water Parameters and Habitat

A curious ability of this species is it’s range of habitats, while originating from Brazil they are capable of moving from fresh to brackish and even identified in marine waters. Could this be why they can shed their skin? But it makes them perfectly adaptable. I have been curious in the past that they need these changes to survive but it seems currently that isn’t true and the main reason they seem to fail in captivity is diet.

Photos of these fishes in the wild show them moving across very varied substrates, they do have some capability to dig in the sand and therefore I’d certainly provide that. I so suspect they are adapted to leaf litter although I find it a pain to clean around without trapping a lot of waste.

References

Carvalho, T. P., Arce, M., Reis, R. E., & Sabaj, M. H. (2018). Molecular phylogeny of Banjo catfishes (Ostaryophisi: Siluriformes: Aspredinidae): A continental radiation in South American freshwaters. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution, 127, 459-467.

Fricke, R., Eschmeyer, W. N. & Van der Laan, R. (eds) 2024. ESCHMEYER’S CATALOG OF FISHES: GENERA, SPECIES, REFERENCES. (http://researcharchive.calacademy.org/research/ichthyology/catalog/fishcatmain.asp). Electronic version accessed 06 May 2024.

Wetzel, J., Wourms, J. P., & Friel, J. (1997). Comparative morphology of cotylephores in Platystacus and Solenostomus: modifications of the integument for egg attachment in skin-brooding fishes. Environmental Biology of Fishes, 50, 13-25.