While my fascination is largely with Loricariids, rasping species are interesting. Unlike the majority of fishes who are limited in what they can eat by the size of their mouth rasping fishes are not and yet ecologically seem very misunderstood. It’s also no lie that I have a soft spot for loaches and have kept quite the diversity of different species.

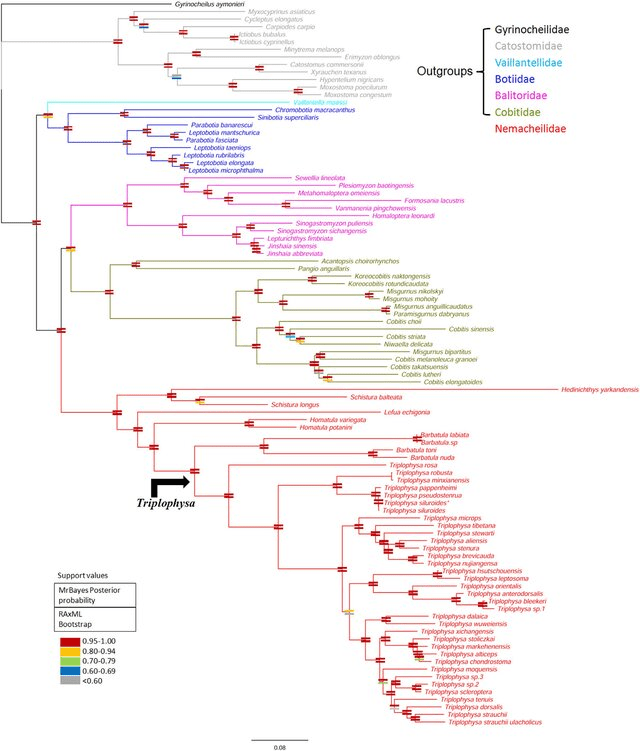

Balitoridae are those dorsio-ventrally flattened loaches from the group Cypriniformes, often referred to the superfamily Cobitoidea. So while Balitoridae are commonly confused with pleco’s, Loricariids they are actually more closely related to carp, barbs and minnows.

There are many genera we keep under this group in the trade, the most common being Sewellia lineaolata but otherwise followed by a variety of species from the genera Pseudogastromyzon and Gastromyzon. Occasionally other genera appear but as by catch many other Sewellia come into the trade such as SEW001 and S. breviventralis. If you want a rare fish and can do some research, it’s not difficult to find something rare or unusual in this group.

Not all have this extreme suction cup-like morphology, some are much more elongate.

The Habitats

As the name suggests these fishes seem to be highly riverine, rocks and high velocity water. There is little to no botanicals, wood and certainly no plants but this clear water (Randall et al., 2023) is where algae can thrive where plants cannot compete. These fishes thrive in a habitat more similar to some Ancistrus, Chaetostoma or Astroblepus would in South America.

Balitoridae Diets

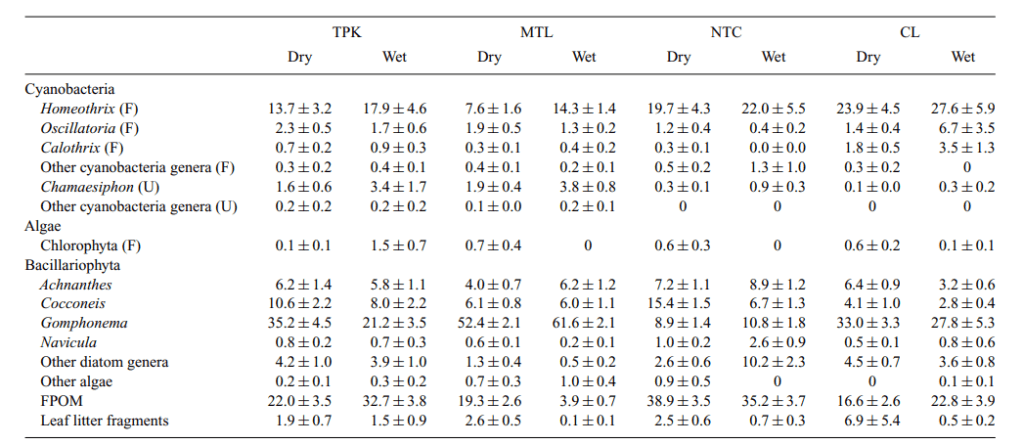

Balitoridae no doubt shows likely a wide range of diets, there doesn’t seem to be the research on them. While few studies exist of these fishes diets the evidence suggests the genus Pseudogastromyzon feeds largely on algaes, both cyanobacteria and traditional Chlorophytic algaes (Fig 1; Yang & Dudgeon, 2010).

Although a later study inferred Pseudogastromyzon myersi feeds on 60-100% of their diet is algaes, with a lot of diversity. In comparison another genus with a similar body morphology, Liniparhomaloptera while feeding on largely algae’s displayed a diet of largely 6-20% invertebrates (Mantel et al., 2004). This is also displayed in Homaloptera sp. which feeds on around 13-14% insects, although the majority of their diet is detritus (Fuadi et al., 2016). As discussed before detritus is a vague classification and could realistically mean anything, it is most likely ‘bacteria’ over waste. A large amount of invertebrates consumed by Homaloptera is ostracods and aquatic larvae, it seems that they feed on minimal algae’s (Nithirojpakdee et al., 2014).

The most unusual thing seems to be this is the only study on the diet of Balitoridae, the majority of studies as with other groups has focused in their phylogenetics and taxonomy (Yang, 2008).

The Dietary Morphology

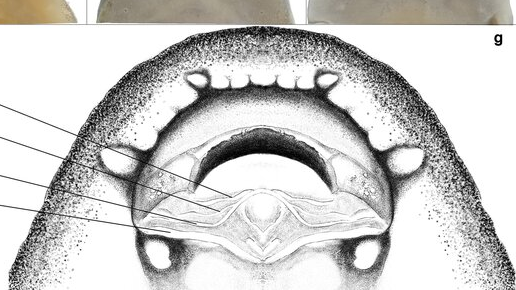

Surprisingly here we have a really good comparison of morphology just externally, compare Gastromyzon, Sewellia etc. with Liniparhomaloptera and immediately their head is much wider. We can some what assume a wider head correlates with a wider jaw and wider jaws, more numerous teeth correlates with a more algivorous diet (Lujan & Armbruster et al., 2012). If we look at the ventral morphology of these fishes one has much wider jaws then the other, Pseudogastromyzon has comparatively wider jaws and general head size then Liniparhomaloptera but is still wider then Homaloptera. The two former species, similar to Sewellia display jaws more similar to Loricariids, plate like jaws with numerous teeth.

There is some obvious jaw diversity in Balitoridae, the mouth of Gastromyzon is much wider then the curved mouth of Sewellia (Willis et al., 2019). I can assume that Gastromyzon is much more similar to Pseudogastromyzon ecologically and regarding diet although they are not closely related (Shao et al., 2020). There is no doubt either species probably feeds on a large amount of algae and other microbial films, but without any ecological records we can only assume.

The shape of the jaw isn’t just about taking up the food but can also be related to being able to extract that food item, while wide, those curved jaws could infer a niche involving extracting microbes from the cracks in rocks and between rocks. Although these cracks, fishers etc. are unlikely to have as many of these microbial films compared to where invertebrates might find refuge. There could be a rugosity aspect as if that habitat has rocks that are naturally bumpy it makes sense to have those more curved jaws then a long jaw which could be unable to access some of these films. A bit like a hoover, you have one part for large flat areas and another to deal with areas that aren’t so flat.

Unlike Loricariids I do not feel looking at their jaws they quite share the exact same niche as they seem to lack the same morphology. Perhaps this is exclusive to siluriformes and there are rasping catfishes in Africa and Asia.

Similar to Loricariids (Krings et al., 2023) it’s is likely not just about the skeletal anatomy that infers diet. The soft tissues at the mouth could play a role as displayed in Chen et al. (2023), there are many ridges on the mouth of the Pseudogastromyzon included these might play a role in sticking to surfaces in their high velocity environment but perhaps when feeding aid in the removal of algaes from a surface.

What should you feed hillstream loaches?

Regardless of the diversity of Balitoridae diets, the majority of their diet is still either detritus and/or algae’s. So I’d build up from that then maybe including a small range of frozen foods for them to forage for.

A brand like Repashy soilent green would be ideal, it is largely algaes with some invertebrates. Alternatively if you can find the algae based New Life Spectrum, AlgaeMax but a product under the same name is higher in fish meals. In the Bag Tropical Fishkeeping UK’s pleco pops would also be great.

It is really tricky to find diets that contain a reasonable volume of algae’s, even if they are listed as algae wafers. Vegetables and cereals do not make up nutritionally for algaes either. At the end of the day if you can’t get these diets then these fishes are not tricky to feed and making your own gel diet is possible, I will maybe write an article about that in future.

References:

Chen, J., Chen, Y., Tang, W., Lei, H., Yang, J., & Song, X. (2023). Resolving phylogenetic relationships and taxonomic revision in the Pseudogastromyzon (Cypriniformes, Gastromyzonidae) genus: molecular and morphological evidence for a new genus, Labigastromyzon. Integrative Zoology.

Fuadi, Z., Naira, K. B., & Hasri, I. 2016. HABITS EATING FISH OF ILI (Homaloptera Sp.) PESTAK RIVER DISTRICT IN CENTRAL ACEH INDONESIA.

Krings, W., Konn-Vetterlein, D., Hausdorf, B., & Gorb, S. N. (2023). Holding in the stream: convergent evolution of suckermouth structures in Loricariidae (Siluriformes). Frontiers in Zoology, 20(1), 37.

Lujan, N. K., & Armbruster, J. W. (2012). Morphological and functional diversity of the mandible in suckermouth armored catfishes (Siluriformes: Loricariidae). Journal of Morphology, 273(1), 24-39.

Mantel, S. K., Salas, M., & Dudgeon, D. (2004). Foodweb structure in a tropical Asian forest stream. Journal of the North American Benthological Society, 23(4), 728-755.

Nithirojpakdee, P., Beamish, F. W. H., & Boonphakdee, T. (2014). Diet diversity among five co-existing fish species in a tropical river: integration of dietary and stable isotope data. Limnology, 15, 99-107.

Randall, Z. S., Somarriba, G. A., Tongnunui, S., & Page, L. M. (2023). Review of the spotted lizard loaches, Pseudohomaloptera (Cypriniformes: Balitoridae) with a re‐description of Pseudohomaloptera sexmaculata and description of a new species from Sumatra. Journal of Fish Biology, 102(1), 225-240.

Shao, L., Lin, Y., Kuang, T., & Zhou, L. (2020). Characterization of the complete mitochondrial genome of Balitora ludongensis (Teleost: Balitoridae) and its phylogenetic analysis. Mitochondrial DNA Part B, 5(3), 2308-2309.

Wang, Y., Shen, Y., Feng, C., Zhao, K., Song, Z., Zhang, Y., … & He, S. (2016). Mitogenomic perspectives on the origin of Tibetan loaches and their adaptation to high altitude. Scientific reports, 6(1), 29690.

Willis, J., Burt de Perera, T., Newport, C., Poncelet, G., Sturrock, C. J., & Thomas, A. (2019). The structure and function of the sucker systems of hill stream loaches. bioRxiv, 851592.

Yang, Y. (2008). The ecology of a herbivorous fish (Pseudogastromyzon myersi: balitoridae) and its influence on benthic algal dynamics in four HongKong streams. HKU Theses Online (HKUTO).

Yang, G. Y., & Dudgeon, D. (2010). Dietary variation and food selection by an algivorous loach (Pseudogastromyzon myersi: Balitoridae) in Hong Kong streams. Marine and Freshwater Research, 61(1), 49-56.