Cichlids, cichlidae are no doubt the classic model group for the study of evolution, they display a wide diversity of morphology in both the America’s and Africa (Arbour & López‐Fernández, 2024; Santos et al., 2023). There are 1727 species in the group cichlidae making this family currently the largest family of fishes. (Fricke et al., 2024). Cichlids both sides of the Atlantic are popular in the aquarium hobby, partially due to their diversity (no doubt colouration) but also their comparatively heightened aggression compared to other clades. No doubt aggression is where many people empathize with with these fishes.

What do cichlids specialize in?

Not unexpected, many species lack a complete understanding of their diet to say what they are actually feeding on. This is a vast topic given the number of species, there are algivores (algae specialists) such as reported in Tropheus (Wagner et al., 2009) to piscivory in peacock bass, Cichla (Aguiar‐Santos et al., 2018). No doubt given I said that Tropheus are reported algivores means I can’t find any solid evidence that they are, this is certainly a topic that needs the right wording and ambiguity included where it might be unsure.

Morphology

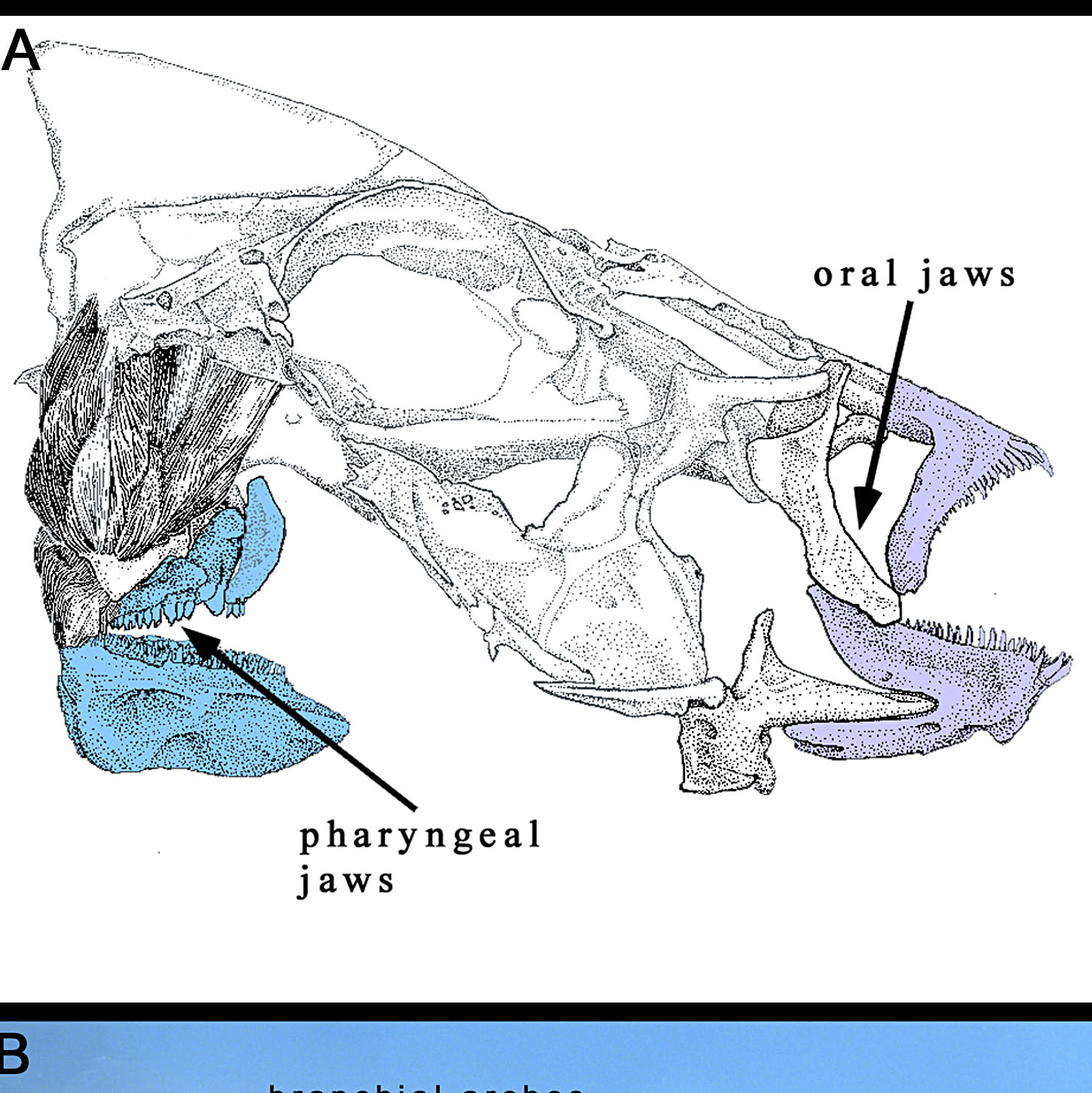

Much of the research into cichlid morphological disparity has long focused on the jaws. Cichlids like many fishes have two pairs of jaws. The oral jaws evolved for prey capture, the pharyngeal jaws evolved for prey processing (Fraser et al., 2009). To some extent the lips might also provide a purpose in some fishes in some fishes to move a surface to extract food further as seen in other fishes (Krings et al., 2023; Cohen et al., 2023).

These two pairs of jaws can be diverse in shape and structure but the teeth further vary between individuals and species.

Cichlids display a very traditional head shape that reflects most other fishes. The oral jaw is often gape limited and evolved to reach forwards to remove or capture a prey item. Realistically no cichlids lack this.

Earlier I mentioned Tropheus being algivores yet it doesn’t seem there is any solid evidence that they exclusively are but we can look at the fishes morphology. They are extremely similar to a fish we know likely consumes a lot of bacteria, algae and similar microbes, discus, Symphysodon (Crampton, 2008). These fishes are not related and this similar morphology is likely due to convergent evolution. Both display a shorter blunter head with strong lips, similar to silver dollars and pacu, Serrasalmidae who some force to break apart at that ‘herbivorous matter’ (Cohen et al., 2023), but they do take it to a more extreme level given they are feeding on plant and fruit matter not algaes and bacteria. Tropheus display some densely packed oral teeth (Richardson-Coy, 2017). This differential oral, mouth morphology could really be due to the differences in what is required to feed on different algaes and in fact, Tropheus are confirmed to specialize in diatoms (Richardson-Coy, 2017), diatoms cling to a surface so much more then the more loose algae/biofilm based diet of Symphysodon (Crampton, 2008) so the more numerous teeth would be more effective. Tropheus oral teeth remind me much more of the jaws of Baryancistrus and similar Loricariids who are scraping algaes of rocks. These teeth might be much more useful for feeding on those Discus, Symphysodon display reduced pharyngeal jaws (Burress, 2016) as this diet might not require the same level of processing as plant matter (hence Serrasalmidae have large robust oral teeth). It seems unclear as to the morphology At the end of the day algivores are diverse, no more needs said but just look at the diversity of algivores in Loricariidae, the queens of algivory/detritivory.

In comparison to Tropheus and Symphysodon would be those that specialize in fishes, Cichla as mentioned before has that large and explosive jaw to reach and consume fish. Fishes are a comparatively more difficult food item to obtain then anything herbivorous so quickly grabbing food much more ahead is beneficial.

The position of jaws is a big clue as to what fishes feed on, terminal mouth’s point forward inferring feeding in front of the fish and is usually associated with carnivory. An inferior mouth points downwards so feeding from the bottom, benthic usually associated with invertebrates and herbivory. Superior mouth’s point upwards and therefore specialize in feeding from the surface. We can clearly see while not extreme Tropheus particularly has an inferior mouth whereas Cichla, being a piscivore is terminal.

While these jaw shapes I mention cover the more traditional cichlids we cannot forget the earth eaters, those fishes who find their food in the substrate, shifting and moving around the sand or silt. While this is generally associated with many Geophagini such as Geophagus, Satanoperca but this clade does include species who are limited in this ability to move substrate e.g. Apistogramma, Mikrogeophagus. Distantly related to these other South American genera is Retroculus, another ‘earth-eater’ (Lopez-Fernandez et al., 2012). The substrate feeding trophic niche seems mostly associated with South American cichlids but it is found in the Rift Valley, although much of this behaviour might be more about breeding sites. Interestingly, it seems these substrate interacting cichlids are more then often mouth-brooders. Substrate digging seems much common in many more Rift Valley clades we keep.

The interesting thing some what I can infer from Burress (2016) is that while jaw shapes might be similar tooth shapes seem divergent between neotropical (fishes from the America’s) and old world (Africa, Asia etc.) regardless of a shared niche. This seems to move away from convergent evolution and multiple solutions to the same problem, the same problem as I noticed being a similar diet.

Liem’s Paradox

This is the biggest part of the cichlid story. To put simply Liem’s paradox is the fact that while fishes might display specialist diets and morphology, they still are capable of generalization. This theory is based on the behaviour and morphology of Rift Valley cichlids (Liem, 1980). This I can assume is some factor limiting morphology for further specialization in morphology, and we see these extreme specializations in other clades e.g. Loricariidae, Gymnotiformes and Moryridae. This plays out in the wild where algivores, Lepidophages (scale specialists) and other niches are shown to feed on fishes when given the chance (Golcher-Benavides & Wagner, 2019). Perhaps there is a nutritional reason, but just because a fish will eat something it doesn’t mean they eat it frequently or it is good for them. This plays out in our aquariums, discus Symphysodon will eat smaller tetra yet they are detritivores and Rift Valley algivorous cichlids (Hata et al., 2014).

It is well accepted that fishes feed and act very differently in the aquarium to how they would in the wild but it does occur in the fishes natural habitats (Golcher-Benavides & Wagner, 2019). This theory in fishes is largely based on Rift Valley cichlids, it’s quite clear that Tropheus are much more capable of generalism then Symphysodon. This opportunistic generalism would be limited by certain specialist morphology e.g. the body shape of Symphysodon or mouth shape of angelfish (Pterophyllum). The Symphysodon is limited in it’s ability to feed on fishes and invertebrates but the Pterophyllum is limited in it’s ability to eat algae’s.

This might not be so much of a simple topic with so many taxa. With the focus on Africa, there is so much we seem not to know about the South American clades despite their diversity. Regardless many cichlids while specialist do not seem to take it to the extreme, this might be behind their diversity but also why unlike clades like Siluriforme, they are limited in that morphological disparity.

References:

Aguiar‐Santos, J., deHart, P. A., Pouilly, M., Freitas, C. E., & Siqueira‐Souza, F. K. (2018). Trophic ecology of speckled peacock bass Cichla temensis Humboldt 1821 in the middle Negro River, Amazon, Brazil. Ecology of Freshwater Fish, 27(4), 1076-1086.

Arbour, J. H., & López‐Fernández, H. (2014). Adaptive landscape and functional diversity of Neotropical cichlids: implications for the ecology and evolution of Cichlinae (Cichlidae; Cichliformes). Journal of evolutionary biology, 27(11), 2431-2442.

Burress, E. D. (2016). Ecological diversification associated with the pharyngeal jaw diversity of Neotropical cichlid fishes. Journal of Animal Ecology, 85(1), 302-313.

Cohen, K. E., Lucanus, O., Summers, A. P., & Kolmann, M. A. (2023). Lip service: Histological phenotypes correlate with diet and feeding ecology in herbivorous pacus. The Anatomical Record, 306(2), 326-342.

Crampton, W. G. (2008). Ecology and life history of an Amazon floodplain cichlid: the discus fish Symphysodon (Perciformes: Cichlidae). Neotropical Ichthyology, 6, 599-612.

Fraser, G. J., Hulsey, C. D., Bloomquist, R. F., Uyesugi, K., Manley, N. R., & Streelman, J. T. (2009). An ancient gene network is co-opted for teeth on old and new jaws. PLoS biology, 7(2), e1000031.

Fricke, R., Eschmeyer, W. N. & Van der Laan, R. (eds) 2024. ESCHMEYER’S CATALOG OF FISHES: GENERA, SPECIES, REFERENCES. (http://researcharchive.calacademy.org/research/ichthyology/catalog/fishcatmain.asp). Electronic version accessed 04 August 2024.

Golcher-Benavides, J., & Wagner, C. E. (2019). Playing out Liem’s paradox: opportunistic piscivory across Lake Tanganyikan cichlids. The American Naturalist, 194(2), 260-267.

Hata, H., Tanabe, A. S., Yamamoto, S., Toju, H., Kohda, M., & Hori, M. (2014). Diet disparity among sympatric herbivorous cichlids in the same ecomorphs in Lake Tanganyika: amplicon pyrosequences on algal farms and stomach contents. Bmc Biology, 12, 1-14.

Krings, W., Konn-Vetterlein, D., Hausdorf, B., & Gorb, S. N. (2023). Holding in the stream: convergent evolution of suckermouth structures in Loricariidae (Siluriformes). Frontiers in Zoology, 20(1), 37.

Liem, K. F. (1980). Adaptive significance of intra-and interspecific differences in the feeding repertoires of cichlid fishes. American zoologist, 20(1), 295-314.

Lopez-Fernandez, H., Winemiller, K. O., Montana, C., & Honeycutt, R. L. (2012). Diet-morphology correlations in the radiation of South American geophagine cichlids (Perciformes: Cichlidae: Cichlinae). PLoS One, 7(4), e33997.

Richardson-Coy, R. (2017). Feeding Selectivity of an Algivore (Tropheus brichardi) in Lake Tanganyika. PhD Thesis

Santos, M. E., Lopes, J. F., & Kratochwil, C. F. (2023). East African cichlid fishes. EvoDevo, 14(1), 1.

Wagner, C. E., McIntyre, P. B., Buels, K. S., Gilbert, D. M., & Michel, E. (2009). Diet predicts intestine length in Lake Tanganyika’s cichlid fishes. Functional Ecology, 23(6), 1122-1131.