Eels constantly cause fascination within aquarists but many true eels, Anguilliformes are simply too large for the majority of aquarists. A much smaller but fascinating alternative comes from Cypriniformes, a relatively medium sized genus known as Pangio. I’ve previously owned Pangio for many years and they are one fish I would definitely keep again.

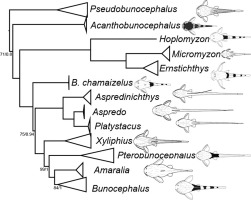

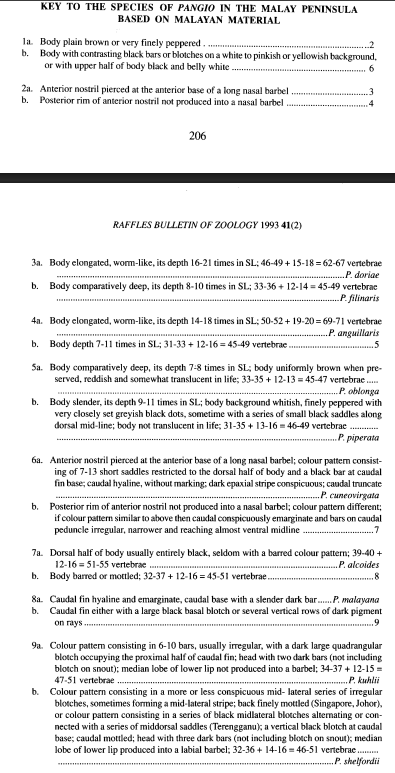

Pangio contains around 32 species (Bohlen et al., 2011), exclusive to South East Asia. They are clearly small anguilliform (the eel shape, not the taxa) but borderline very similar to the larger loach relative, Misgurnus anguillicaudatus (weather loach). For the aquarist the taxonomy can prove confusing with revisions that are not always well known such as the synonymy of Pangio semicincta and Pangio kuhlii (Kottelat, M & Lim, 1993) but is frequently debated seemingly with little explanation as to why (Eschmeyer, 2025). Molecular phylogenetics hasn’t seemed to have solved the confusion, or it’s suggested that the two species are the same (Bohlen et al., 2011). Another problem is Pangio myersi is nested within the two (Bohlen et al., 2011) although easily diagnosed for aquarists by thick barring from dorsal to abdomen (Kottelat, M & Lim, 1993).

There doesn’t seem to be immediately much morphological diversity in this genus, there is a diversity of patterning. While many will attempt diagnosing species by colouration, this has been called into question with solid marked individuals being identified as those with stripes (Bohlen et al., 2011). Like all loaches they contain small scales that to some can make them seem scaleless.

My interest is largely in morphology and like many there seems to be no anatomical studies. The majority focuses in the taxonomic records and this makes it really difficult to understand the morphology that might have ecological importance and also husbandry. We can clearly see a inferior (ventrally facing) mouth so they feed below and given the barbels it seems a common trait with those rooting in the substrate given they are not mobile.

In the aquarium hobby we keep very few species but a diversity is starting to be imported and not just as bycatch. You can expect to find of the distinctively patterned species Pangio semicincta/kuhlii, P. myersi and P. shelfordii. The smallest species that is now being imported in reasonable numbers is Pangio cuneovergata. There are a few solid coloured species and these are likely Pangio oblonga and P. anguillaris, potentially also P. malayana who is shown to have solid individuals.

How to Identify your Pangio?

This is a tricky topic but there are multiple sources that holds clues.

As described previously there are some hints you can get from experiencing the species in captivity but there is a lot of cross referencing, where you can linking to a locality and exploration of images that could be of use. I find Bohlen et al. (2011; Fig 1) possibly the most useful of the papers for identification of species even if images are limited. One must also remember where you might have imported from one country it doesn’t mean that is where it is caught.

Habitat

There is little ecological details on these fishes. Habitat likely differs per species. Largely found in blackwater although potentially also highly turbid waters with variable or seasonal currents (Bohlen et al., 2011). Yet in the literature very little else is recorded.

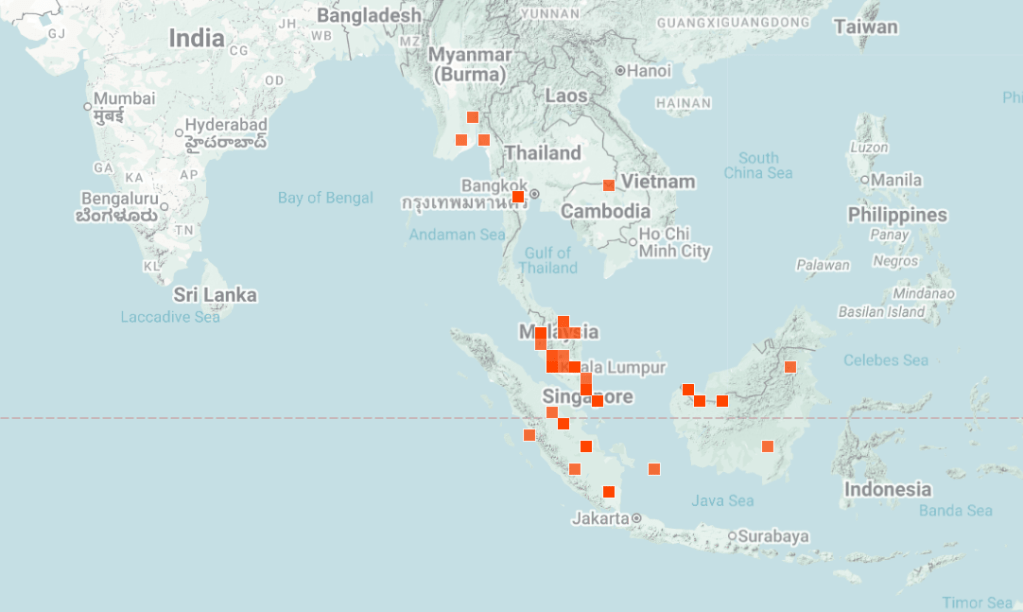

Some assumptions can be made from the locality of these fishes (Fig 2), particularly in reference to temperature, although you will also need to check against elevation and other factors such as is the water body sheltered and therefore cooler. INaturalist (https://www.inaturalist.org/)and GBIF (https://www.gbif.org/) can be useful here although neither make any records of environmental factors. If someone is familiar with these websites then there is other extractions of data that can be done but I am not someone who works with species distributions. Other parameters can be tricky without knowing the geology of the region, some rocks dissolve more readily whereas others allow tannins or just rainwater to drain rapidly through without dissolving minerals.

We also know Pangio almost always seem to breed in tanks with gravel, there are probably exceptions so the substrates must have gravel where they are located with the exception of maybe more elongate species who similar to lamprey bury in silt and sands.

What setup would suit Pangio?

Generally I don’t think the current ideal setup for Pangio needs any adapting, sandy areas and gravel based areas, leaf litter providing many hiding places but also wood or rocks for more solid refuges.

A reasonable current but it wouldn’t have to be that strong so a sponge filter would suffice. I would consider with externals, internals or similar filters whether the fishes could get in, they are notorious for finding their ways into filters so either providing an inlet guard or changing filtration method particularly for those like Pangio cuneovergata. Undergravel filters sound great and somewhat are, the fishes will make their way into them and likely also live below the grids but many do report them spawning well there.

There is no doubt these fishes come from more soft acidic water based on locality and therefore I recommend a pH of around 6-7.5 for various reasons. There is flexibility and these fishes have proven themselves very hardy in captivity. Total Dissolved Solids (TDS) below 200ppm but ideally below that 100ppm range unless your water has potentially skewed values. Temperature is definitely the tricky one without knowing exactly the temperature of their caught locality, I would personally cross reference where they are found with water temperatures of the area and who knows other species in the area might have ecological data. Generally 24-28c seems the most ideal but you could be flexible particularly on that upper end to go higher.

They are often noted as being particularly shy although I’ve found with dimmer and dappled lighting but also frequent exposure they don’t seem to be that shy and show a lot of normal feeding and explorative behaviour. Plenty of cover gives them somewhere to retreat to.

References:

Bohlen, J., Šlechtová, V., Tan, H. H., & Britz, R. (2011). Phylogeny of the southeast Asian freshwater fish genus Pangio (Cypriniformes; Cobitidae). Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution, 61(3), 854-865.

Kottelat, M & Lim, K. K. P. (1993) A review of the eel-loaches of the genus Pangio (Teleostei:Coditidae) from the Malay Peninsula, with descriptions of six new species. Raffles of Zoology, 41(2): 203-249.