Many fishes display lumps, spots and bumps which can happen due to a range of pathological conditions whether it being pathogens or other factors. These can easily be confused and if concerned or confused please consult a fish pathologist or trained fish specialist veterinarian. This page is only to help give some clarity

All sources here are from scientific papers and many of the images from these papers for a reliable diagnosis unless otherwise stated for clarity purposes.

Microscopy is required in many cases for a confirmed diagnosis and therefore I recommend their use. Some stores might have one available to be used. In other cases more advanced diagnostic techniques might be required and provided by a pathologist via a veterinarian.

Diseases featured:

- White spot/ich (Ichthyophthirius multifiliis)

- Velvet (Oodinium, Piscinoodinium and other dinospores) and related taxa

- Dermocystidium

- Worm cysts

- Tumors

- Viral papilloma and herpes viruses

- Unknown growths

White spot/ich (Ichthyophthirius multifiliis)

Protozoan ciliate pathogen which can cause large mortalities in later stages.

Occurrence: Seems to be very common and in my opinion largely occurs when fish are sufficiently stressed.

Diagnostics: White spots on the body of the fish, can also be accompanied by shedding of the slime coat. The spots can be varied in size and number. This ciliate additionally targets the gills where it causes the most stress on the fish (Yang et al., 2023; Mallik et al., 2013). This spotted appearance is commonly confused with Epistylis which if symptomatic (of which mostly it is not) appears more as a plaque so will not appear in this article (ESHA video; Ksepka et al., 2021; Valladao et al., 2015; Wang et al., 2017, Wu et al., 2021). Both pathogens can appear with Aeoromonas bacteria that additionally causes hemorrhaging (Kumar et al., 2022).

Microscopic image:

Treatment: The most frequent treatments provided in the aquarium hobby is malachite green with either formalin, formaldehyde or copper. Obviously copper is often a concern for those with invertebrates in the aquarium. Salt the old age treatment can work and as a study ABDULLAH-AL MAMUN et al. (2021) infers it depends on time of treatment. There seems to be a multitude of papers narrowing down the best treatment and to me this infers maybe there is no real answer, there might be increasing immunity of the ciliate or just this species is so diverse. Generally it’s assumed the best method is to avoid introducing any fish showing symptoms or on the same system with those who do. Copper sulphate additionally has been shown to treat white spot (Schlenk et al., 1998). In a later 2008 study formalin did not have any effect on the ciliate whereas copper treated it within 14 days (Rowland et al., 2008) which is around two rounds of treatment by most bottles. I therefore just looking at these three studies would not recommend formalin and maybe therefor formaldehyde for treatment and instead focus on copper and maybe salt needs further examination.

Velvet (Oodinium, Piscinoodinium and other dinospores) and related taxa

One of the most unusual parasites of fishes being an algae known as dinoflagellates.

Occurrence: Reasonably common, I can’t comment on cause. It seems Oodinium seems to be less common then Piscinoodinium.

Diagnostics: Different from white spot, being algaes they tend to have some coloration to them. Usually appears as small golden spots across the body, the fish are often lethargic. Mortality is not particularly rapid (Levy et al., 2007). It is not always obvious beyond hemorrhaging (Sudhagar et al., 2022).

Microscopic image: Not entirely required and diverse, although can make it easier to compare.

Treatment: Treatment rarely seems discussed. As these are photosynthetic I agree with many aquarists that keeping the lights off for even two weeks will not harm the fish and even if it minorly effects the algae that’s better then nothing. The aquarium hobby largely jumps to copper based treatments along with malachite green mixed in with methylene blue, it doesn’t seem the most resistant pathogen and I wonder additionally if a fishes immune system handles some of it. Copper is suggested to work (Lieke et al., 2020). There seems to be no research on methylene blue other then being an anti-protozoan compound. Similarly with malachite green, no treatments even salt have any strong background to their effectiveness. The other issue is these compounds can effect the microbes within the aquarium (Yang et al., 2021). All I can say is I had success with the NT labs anti-parasite treatment containing copper sulphate and formaldehyde along with switching the lights off.

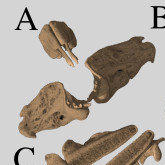

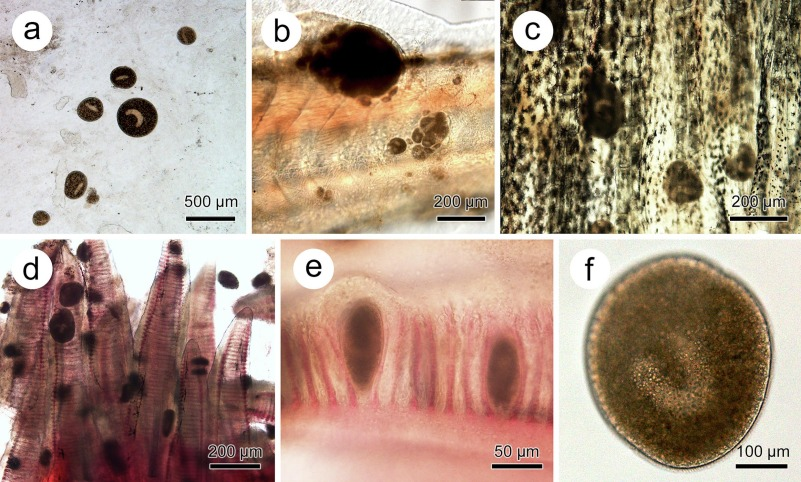

Dermocystidium

The strangest in appearance of pathogens, much like a worm but far from that, their taxonomic placement is unclear but they don’t move.

Occurrence: Reasonably frequent with a diversity of fishes soon after obtaining.

Diagnostics: Worm like in a variety of forms and size, can be encapsulated by pectoral fins or around the body. Some might appear singularly other fishes might have a lot more. These do not move like nematodes but are extremely diverse (Fujimoto, et al., 2018; Persson et al., 2022).

Microscope image: Not required.

Treatment: It is largely agreed in the aquarium trade which I agree that these protozoans as unsightly as they are do disappear with time and handled by the fishes own immune system.

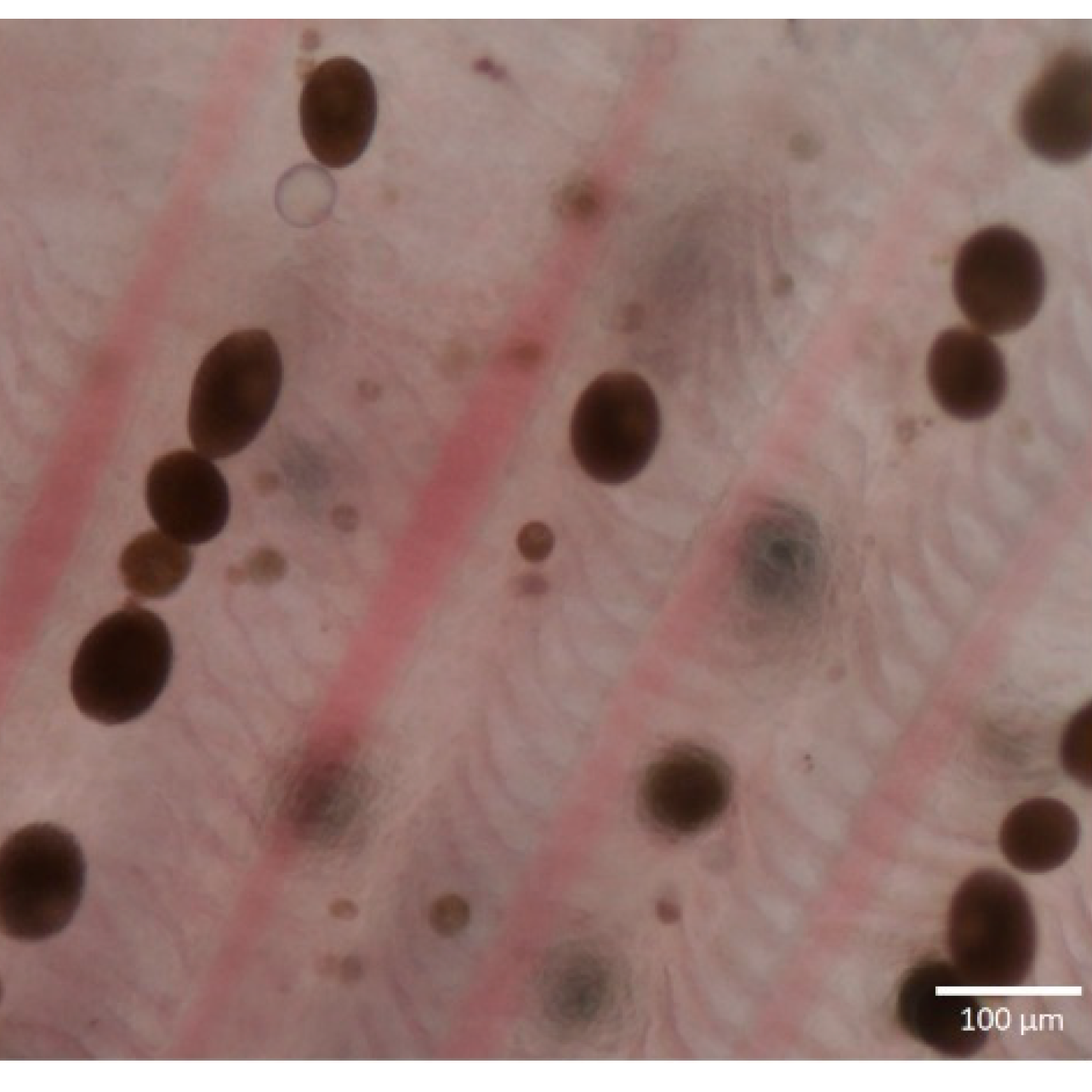

Worm cysts

Not really possible to obtain much scientific research on the topic with the time I have free. But it does happen and seems frequent with wild imports.

Occurrence: Not common at all, seems to arrive with import.

Diagnostics: Looks much like white spot but larger cysts. Stubborn and white spot treatments do not work regardless of the fish showing no lethargy or poor health.

Microscope image: Usually distinctively different from white spot velvet by size and shape.

Treatment: As suggested by the name, wormers tend to work. I cannot remember which I used but likely first praziquantel, levamisole and flubendazole might work as well.

Tumors

If a tumor occurs certainly this is a situation where veterinarians are recommended.

Occurrences: There are many caused within fishes, sometimes it is genetic causes such as in the dragon scale of Betta splendens, viral causes (Coffee et al., 2013) or dietary (Žák et al., 2022). On a quick scan of the literature papilloma viruses are not associated with tumors.

Diagnosis: These can be large growths, they can be vascularized supplied by blood vessels. Unlike viral growths on my observations tend to be rounder and do not appear in many numbers.

Microscopy: Not required.

Treatment: Discuss with a specialist fish veterinarian.

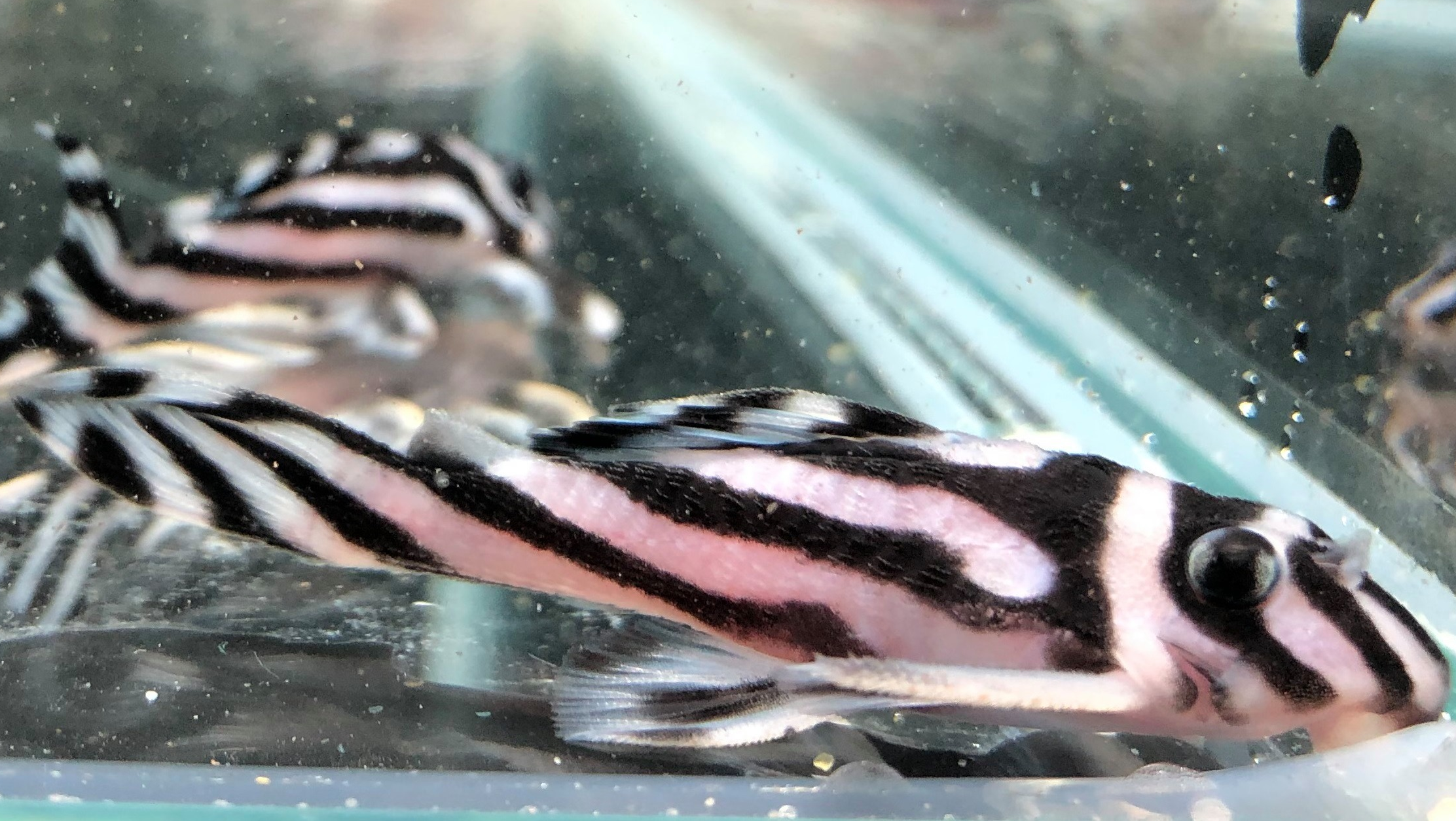

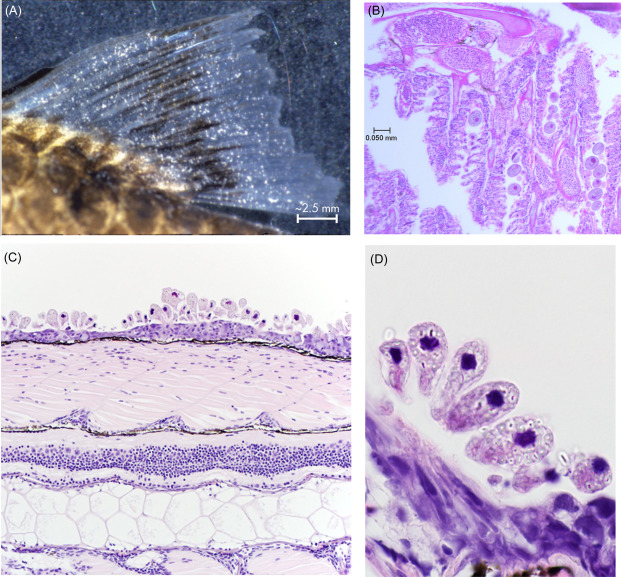

Viral papilloma and herpes viruses

These are commonly mistaken for lymphocystis and can be very complex growths. Technically Papilloma refers to epithelial groups but can display similarly to herpes viruses. In the aquarium trade it doesn’t seem clear which we are handling and regardless treatment is the same. A wide range of herpes viruses are associated with fishes from KHV, carp pox (Davison et al., 2013) and channel catfish herpesvirus (Davison et al., 1992).

Occurrence: Seems reasonably common right now. This virus I can assume once contracted is not removed from the fishes body but are suppressed by the immune system. Koi Herpes Virus (KHV) is fatal and while not wildly common any suspected occurrence might require contacting environmental authorities.

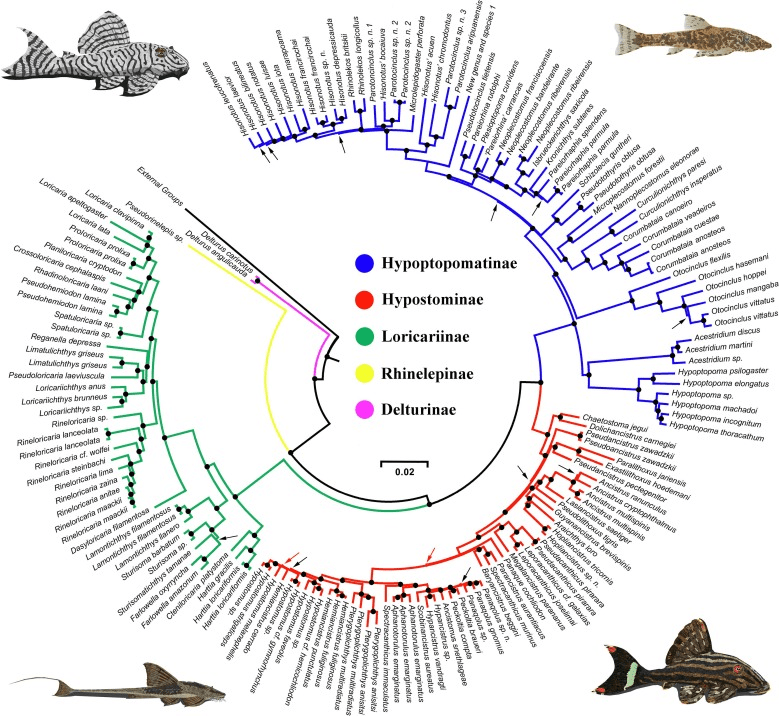

Diagnosis: These are round or very tuberous numerous growths, much more like warts while symptomatic but asymptomatic individuals and time might not display any symptoms (Tarján et al., 2022; Rahmati-Holasoo et al., 2015). Very understudied when it comes to aquarium fishes so whether we are dealing with a herpes or traditional papilloma virus is difficult to say. Rahmati-Holasoo et al. (2015) infers that most viral growths we are seeing in Loricariids is caused by a Papillomavirus, although a previous study by Hedrick et al., (1996) in carp inferred similar growths and concluded due to a herpes virus.

Treatment: Time, these viruses cannot be cured only prevention of introduction. Very few are fatal. These viruses are generally specific to closely related fishes so transfer should not be an issue.

Sources for koi and carp pox:

https://cafishvet.com/fish-health-disease/koi-pox-aka-carp-pox

https://marinescience.blog.gov.uk/2015/10/02/koi-herpesvirus-khv-disease-and-fisheries

Unknown growths

There is a wide range of unknown growths in fishes we can only make assumptions, veterinary professionals and vets would be worth consulting. I have seen a number which didn’t conform with any of these.

References:

ABDULLAH-AL MAMUN, M. D., NASREN, S., RATHORE, S. S., & RAHMAN, M. M. (2021). Mass infection of Ichthyophthirius multifiliis in two ornamental fish and their control measures. Annals of Biology, (2), 209-214.

Coffee, L. L., Casey, J. W., & Bowser, P. R. (2013). Pathology of tumors in fish associated with retroviruses: a review. Veterinary Pathology, 50(3), 390-403.

Davison, A. J. (1992). Channel catfish virus: a new type of herpesvirus. Virology, 186(1), 9-14.

Davison, A. J., Kurobe, T., Gatherer, D., Cunningham, C., Korf, I., Fukuda, H., … & Waltzek, T. B. (2013). Comparative genomics of carp herpesviruses. Journal of Virology, 87(5), 2908-2922.

Esmail, M. Y., Astrofsky, K. M., Lawrence, C., & Serluca, F. C. (2015). The biology and management of the zebrafish. In Laboratory animal medicine (pp. 1015-1062). Academic Press.

Fujimoto, R. Y., Couto, M. V. S., Sousa, N. C., Diniz, D. G., Diniz, J. A. P., Madi, R. R., … & Eiras, J. C. (2018). Dermocystidium sp. infection in farmed hybrid fish Colossoma macropomum× Piaractus brachypomus in Brazil. Journal of Fish Diseases, 41(3), 565-568.

Gomes, A. L. S., Costa, J. I. D., Benetton, M. L. F. D. N., Bernardino, G., & Belem-Costa, A. (2018). A fast and practical method for initial diagnosis of Piscinoodinium pillulare outbreaks: piscinootest. Ciência Rural, 48.

Hedrick, R. P., Groff, J. M., Okihiro, M. S., & McDowell, T. S. (1990). Herpesviruses detected in papillomatous skin growths of koi carp (Cyprinus carpio). Journal of Wildlife Diseases, 26(4), 578-581.

Ksepka, S. P., & Bullard, S. A. (2021). Morphology, phylogenetics and pathology of “red sore disease”(coinfection by Epistylis cf. wuhanensis and Aeromonas hydrophila) on sportfishes from reservoirs in the South‐Eastern United States. Journal of Fish Diseases, 44(5), 541-551.

Kumar, V., Das, B. K., Swain, H. S., Chowdhury, H., Roy, S., Bera, A. K., … & Behera, B. K. (2022). Outbreak of Ichthyophthirius multifiliis associated with Aeromonas hydrophila in Pangasianodon hypophthalmus: The role of turmeric oil in enhancing immunity and inducing resistance against co-infection. Frontiers in immunology, 13, 956478.

Levy, M. G., Litaker, R. W., Goldstein, R. J., Dykstra, M. J., Vandersea, M. W., & Noga, E. J. (2007). Piscinoodinium, a fish-ectoparasitic dinoflagellate, is a member of the class Dinophyceae, subclass Gymnodiniphycidae: convergent evolution with Amyloodinium. Journal of Parasitology, 93(5), 1006-1015.

Lieke, T., Meinelt, T., Hoseinifar, S. H., Pan, B., Straus, D. L., & Steinberg, C. E. (2020). Sustainable aquaculture requires environmental‐friendly treatment strategies for fish diseases. Reviews in Aquaculture, 12(2), 943-965.

Mallik, S. K., Shahi, N., Das, P., Pandey, N. N., Haldar, R. S., Kumar, B. S., & Chandra, S. (2015). Occurrence of Ichthyophthirius multifiliis (White spot) infection in snow trout, Schizothorax richardsonii (Gray) and its treatment trial in control condition. Indian Journal of Animal Research, 49(2), 227-230.

Persson, B. D., Aspán, A., Bass, D., & Axén, C. (2022). A case study of Dermotheca gasterostei (= Dermocystidium gasterostei, Elkan) isolated from three-spined stickleback (Gasterosteus aculeatus) captured in lake Vättern, Sweden. Bulletin of the European Association of Fish Pathologists.

Rahmati-Holasoo, H., Shokrpoor, S., Mousavi, H. E., & Ardeshiri, M. (2015). Concurrence of inverted-papilloma and papilloma in a gold spot pleco (Pterygoplichthys joselimaianus Weber, 1991). Journal of Applied Ichthyology, 31(3), 533-535.

Rowland, S. J., Mifsud, C., Nixon, M., Read, P., & Landos, M. (2008). Use of formalin and copper to control ichthyophthiriosis in the Australian freshwater fish silver perch (Bidyanus bidyanus Mitchell). Aquaculture research, 40(1), 44-54.

Schlenk, D., Gollon, J. L., & Griffin, B. R. (1998). Efficacy of copper sulfate for the treatment of ichthyophthiriasis in channel catfish. Journal of Aquatic Animal Health, 10(4), 390-396.

Sudhagar, A., Sundar Raj, N., Mohandas, S. P., Serin, S., Sibi, K. K., Sanil, N. K., & Raja Swaminathan, T. (2022). Outbreak of Parasitic Dinoflagellate Piscinoodinium sp. Infection in an Endangered Fish from India: Arulius Barb (Dawkinsia arulius). Pathogens, 11(11), 1350.

Tarján, Z. L., Doszpoly, A., Eszterbauer, E., & Benkő, M. (2022). Partial genetic characterisation of a novel alloherpesvirus detected by PCR in a farmed wels catfish (Silurus glanis). Acta Veterinaria Hungarica, 70(4), 321-327.

Valladao, G. M. R., Levy-Pereira, N., Viadanna, P. H. D. O., Gallani, S. U., Farias, T. H. V., & Pilarski, F. (2015). Haematology and histopathology of Nile tilapia parasitised by Epistylis sp., an emerging pathogen in South America. Bulletin of the European Association of Fish Pathologists, 35(1), 14-20.

Yang, C. W., Chang, Y. T., Hsieh, C. Y., & Chang, B. V. (2021). Effects of malachite green on the microbiomes of milkfish culture ponds. Water, 13(4), 411.

Yang, H., Tu, X., Xiao, J., Hu, J., & Gu, Z. (2023). Investigations on white spot disease reveal high genetic diversity of the fish parasite, Ichthyophthirius multifiliis (Fouquet, 1876) in China. Aquaculture, 562, 738804.

Wang, Z., Zhou, T., Guo, Q., & Gu, Z. (2017). Description of a new freshwater ciliate Epistylis wuhanensis n. sp.(Ciliophora, Peritrichia) from China, with a focus on phylogenetic relationships within family Epistylididae. Journal of Eukaryotic Microbiology, 64(3), 394-406.

Wu, T., Li, Y., Zhang, T., Hou, J., Mu, C., Warren, A., & Lu, B. (2021). Morphology and molecular phylogeny of three Epistylis species found in freshwater habitats in China, including the description of E. foissneri n. sp.(Ciliophora, Peritrichia). European Journal of Protistology, 78, 125767.

Žák, J., Roy, K., Dyková, I., Mráz, J., & Reichard, M. (2022). Starter feed for carnivorous species as a practical replacement of bloodworms for a vertebrate model organism in ageing, the turquoise killifish Nothobranchius furzeri. Journal of Fish Biology, 100(4), 894-908.