Hypancistrus have long been an issue for hobbyists and taxonomists providing challenges to identify and define what is a species, over time a few have been described but leaving one of the most common species.

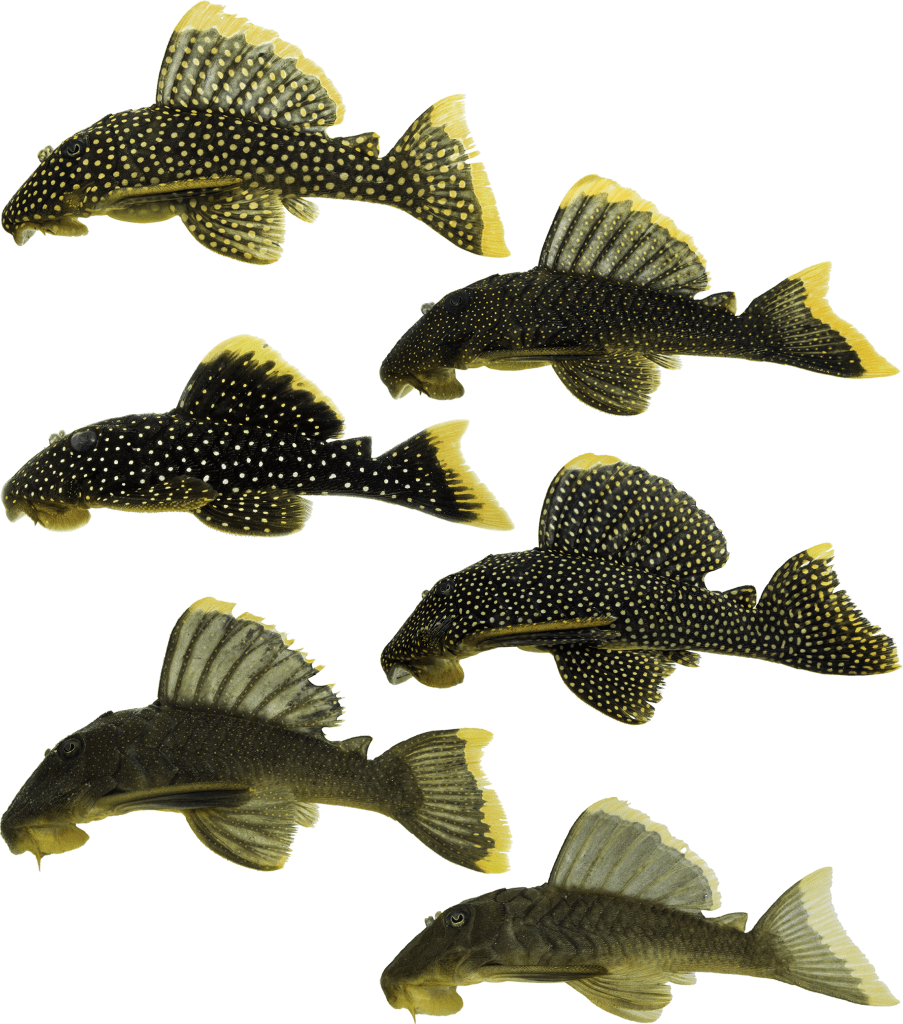

This topic is tricky for scientists regarding how a species is defined and where do you draw a line, even trickier for hobbyists. The Rio Xingu species have been particularly tricky as there are many striped species with only Hypancistrus zebra being particularly distinctive. For the hobbyist the L number system can add to the confusion as while different individuals can be given different L number it doesn’t infer they are different species. Morphology can be tricky to navigate as there are many very diverse species both morphologically and genetically for example Baryancistrus xanthellus (of which does include a green variant, verde that is not B. chrysolomus) or Peckoltia sabaji (Fig 1; Magalhães et al., 2021; Armbruster 2003).

Some of this morphological and genetic diversity can be based on different populations and localities, it is tricky to infer whether there is interbreeding as to when and extent this occurs without detailed analysis for both morphologically and genetically. We also risk drawing lines between populations or individuals of the same species that don’t exist in nature.

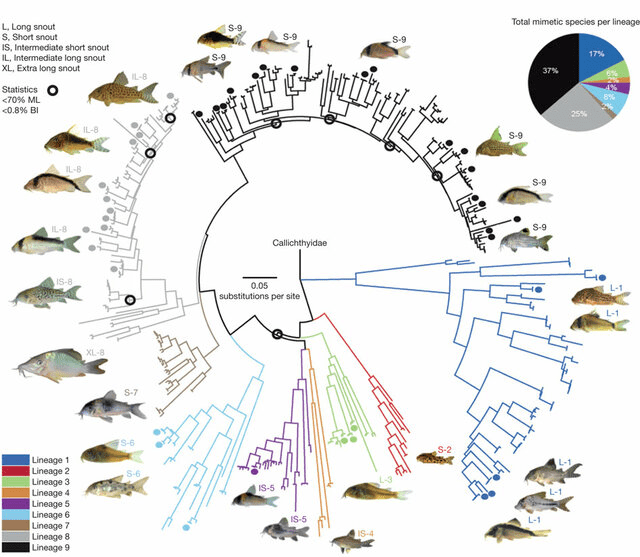

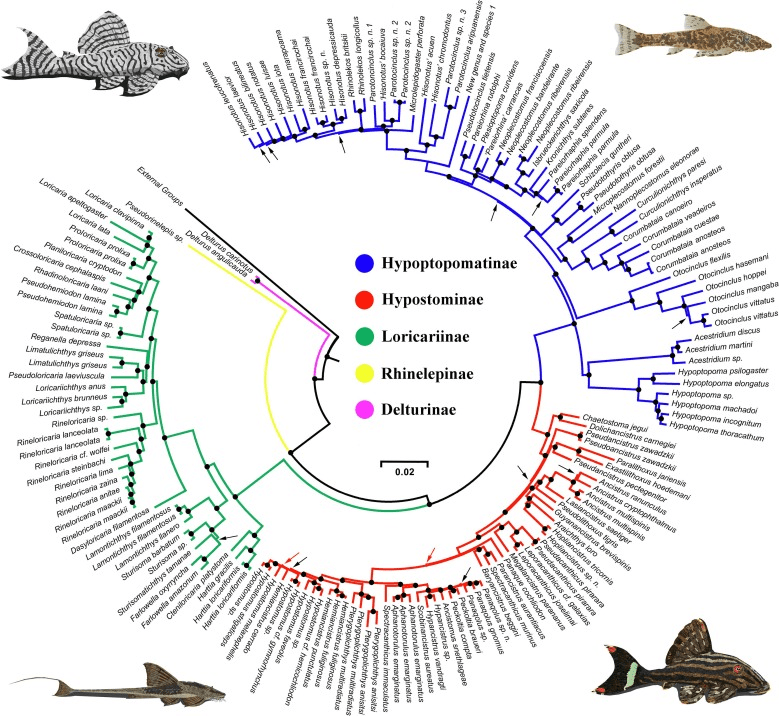

Commonly understood is the importance of species as a biological unit and in some manner it is, but this is no one overarching definition for a species, it’s much more complex then that. As said earlier species can be both morphologically and genetically diverse or not at all, it varies so much and on where the line is drawn. The common misconception is that genetics solves any issues with defining a species but when you create these trees to plot species different genes, regions or even whether you use mitochondrial or nuclear DNA can infer different groupings. But this reliance on species being the important factor that matters for many aquarists ignores much of this and can lead to splitting species into unrealistic groupings. Realistically like the killifish and Poecilidae sides of the hobby, we need to recognize populations are as valuable as species, even if they cross or not. Populations might have unique genetics or morphology, doesn’t make them different species but we should really think through how we breed our fishes and what individuals we choose. If fishes come from different suppliers maybe double checking locality, maybe considering if certain captive bred fishes are useful for maintaining a population.

So in summary just because some species might look different it doesn’t mean they are but doesn’t mean they aren’t distinct populations that shouldn’t be valued.

The Two New Species of Hypancistrus

Description for Hypancistrus seideli and H. yudja:

Sousa LM, Sousa EB, Oliveira RR, Sabaj MH, Zuanon J, Rapp Py-Daniel L. (2025). Two new species of Hypancistrus (Siluriformes: Loricariidae) from the rio Xingu, Amazon, Brazil. Neotropical Ichthyology. 23(1). https://doi.org/10.1590/1982-0224-2024-0080

These exciting descriptions help us understand the Loricariids we keep in the aquariums better and more accurately describe them. Hopefully it leads to further studies of Hypancistrus.

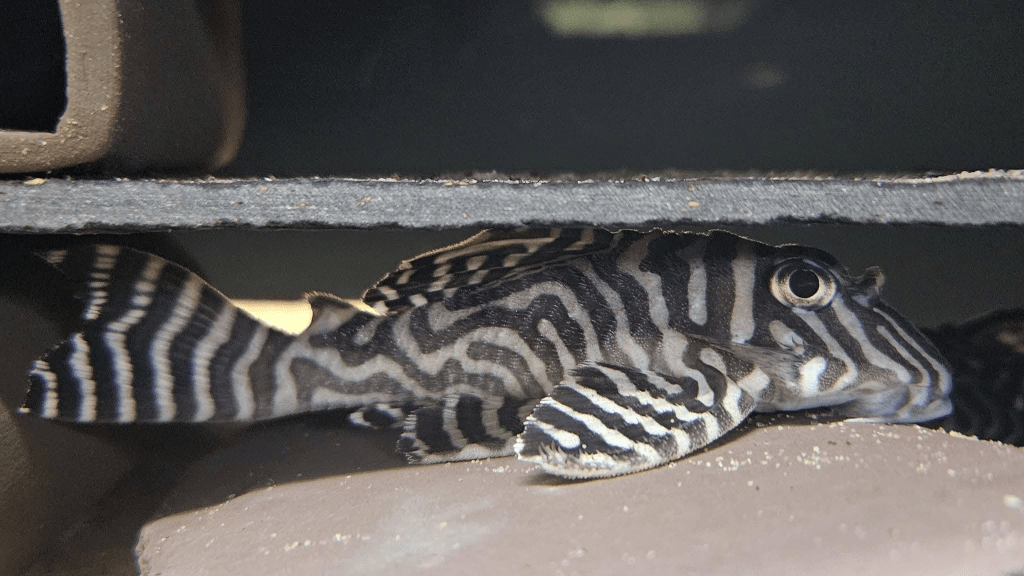

Hypancistrus seideli Sousa, Sousa, Oliveira, Sabaji, Zuanon & Rapp Py-Daniel 2025.

This species includes the L numbers: L333, L066, L236, L287, L399, L400.

This species includes the common names: King tiger pleco, maze zebra pleco.

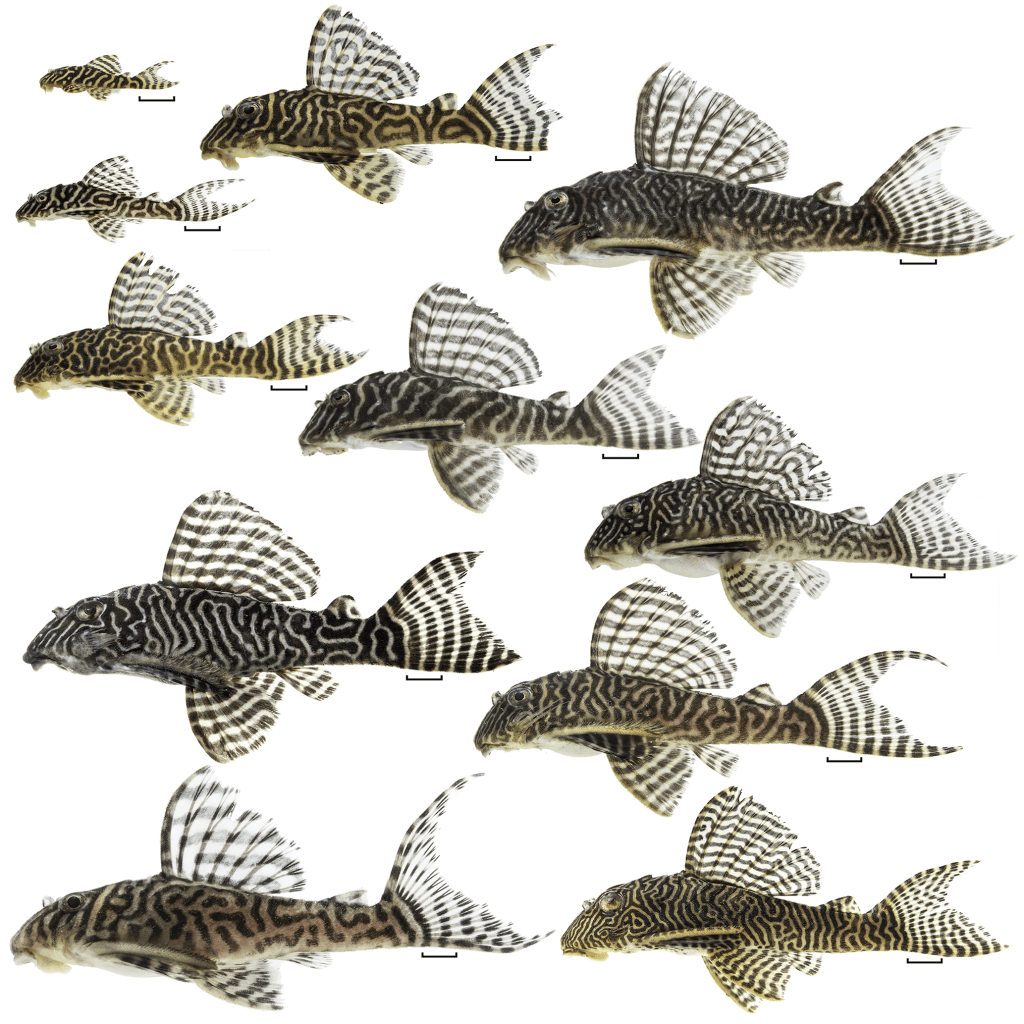

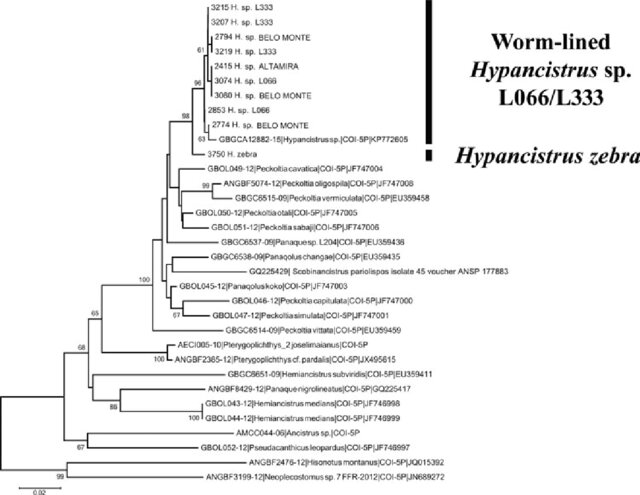

Diagnosed by alternating dark and pale vermiculation’s from currently described species although recognised as extremely varied (Sousa et al., 2025). Hypancistrus seideli covers a wide range of the Hypancistrus diversity in the Rio Xingu and some of the most popular species in the aquarium trade. Although morphologically diverse (Fig 2) there it seems to not have the same amount of molecular diversity so further inferring at least L066 and L333 regardless are the same species. Phylogenetically there also seems to be an issue to designate them as different species given L066 and Belo Monte seem to be paraphyletic (Cardoso et al., 2016). Although using sequences from a public database does rely on correct identification of those sequencing the samples (Fig 3).

Etymology: Hypancistrus seideli is named after the well known and respected aquarist Ingo Seidel who has contributed a lot to the knowledge of Hypancistrus (Sousa et al., 2025).

Habitat: While the paper doesn’t go into detail that isn’t well known it describes their environment as rocky with strong currents (Sousa et al., 2025).

Hypancistrus seideli ‘L066 King Tiger’ Image originated from: Olivia and Dad’s Fish Room https://www.facebook.com/profile.php?id=100063396450007

Hypancistrus yudja Sousa, Sousa, Oliveira, Sabaji, Zuanon & Rapp Py-Daniel 2025.

This species includes the L numbers: L174.

This species includes the common names: Ozelot pleco.

Diagnosed by large brown splotches and saddles on a tanned background (Sousa et al., 2025).

Etymology: Named after the Yudjá people of the Volta Grande, Rio Xingu, Brazil who are located in the same area as these fishes and described as equally threatened by the Belo Monte dam (Sousa et al., 2025).

Habitat: Located specifically from deep but rocky waters but remains hidden in crevices for large amounts of time (Sousa et al., 2025).

References:

Armbruster, J. W. (2003). Peckoltia sabaji, a new species from the Guyana Shield (Siluriformes: Loricariidae). Zootaxa, 344(1), 1-12.

Cardoso, A. L., Carvalho, H. L. S., Benathar, T. C. M., Serrao, S. M. G., Nagamachi, C. Y., Pieczarka, J. C., … & Noronha, R. C. R. (2016). Integrated cytogenetic and mitochondrial DNA analyses indicate that two different phenotypes of Hypancistrus (L066 and L333) belong to the same species. Zebrafish, 13(3), 209-216.

Magalhães, K. X., da Silva, R. D. F., Sawakuchi, A. O., Gonçalves, A. P., Gomes, G. F. E., Muriel-Cunha, J., … & de Sousa, L. M. (2021). Phylogeography of Baryancistrus xanthellus (Siluriformes: Loricariidae), a rheophilic catfish endemic to the Xingu River basin in eastern Amazonia. Plos one, 16(8), e0256677.