With a whole section designated to Loricariidae, I haven’t actually done a beginners guide to the group. This website largely isn’t designed for beginners but Loricariid’s are some of the most misunderstood group of fishes.

- What is a Pleco or Whiptail Catfish?

- What is the L number system?

- Introduction

- The size of plecos

- What should I feed my pleco?

- Do pleco’s need wood?

- What parameters do pleco’s need?

- What decor do plecos require?

- Tankmates

- Recommended websites

- References:

What is a Pleco or Whiptail Catfish?

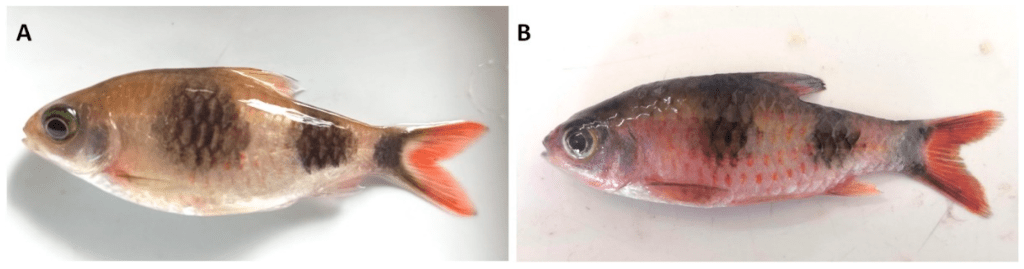

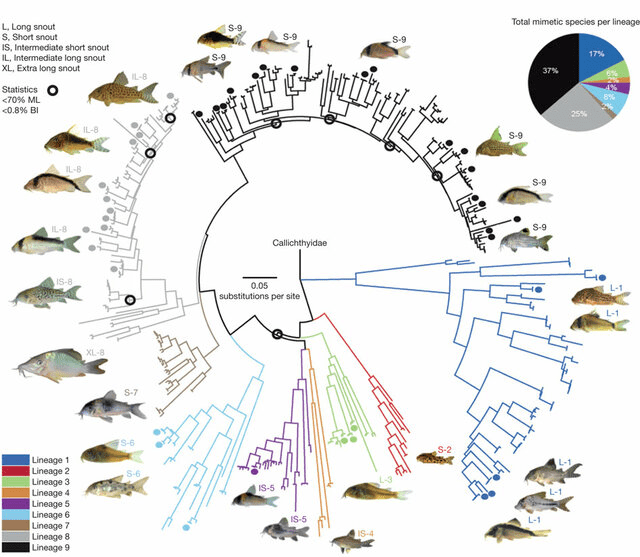

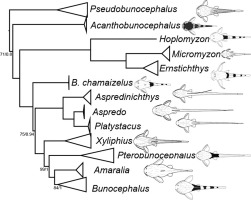

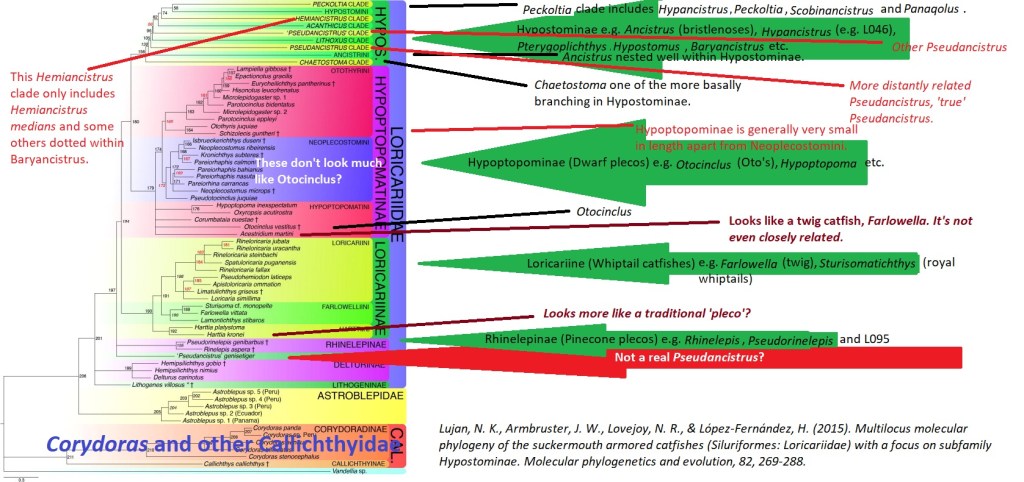

These two common names have no certain definitions, the majority of their use is a pick and mix that varies between the user. It is even more confusing that some loaches are referred to as pleco’s. All common names are equally as valid as each other. I find it easier to refer to the whole of Loricariidae as plecos, why? Figure 1 explains this situation. By excluding the subfamily Loricariinae (whiptail catfishes), you exclude Loricariichthys of which Plecostomus was synonymized with. If you exclude Hypoptopominae (Otocinclus and relatives) then Neoplecostomini and Neoplecostomus are excluded. Ancistrus, commonly known as bristlenose’s places right in the middle of Hypostominae, traditional plecos but Ancistrus also includes the medusa pleco, Ancistrus ranunculus. Then outside of all of these groups is Rhinelepinae, so that includes the pineapple pleco’s, and on it’s own Pseudancistrus genisetiger, so none of those are plecos then?

What would solve the common name issue? Simply not using them. Sadly with Loricariids you can’t avoid scientific names as many species do lack common names or share them.

What is the L number system?

The L number system is actually quite simple, it is a hobby made system originating from the German Magazine, DATZ. It simply designates an L number to a variant or species. It is commonly stated that undescribed species are given L numbers, this is partially true but there are many species who were described decades or over 100 years before given their L number such as the sailfin/common/leopard pleco, Pterygoplichthys gibbiceps who was described by Kner in 1854.

I am not entirely convinced the L number system is easy to use, the order of the numbers doesn’t infer anything regarding the fishes care or lineages. Multiple species can share an L number e.g. Baryancistrus demantoides and Hemiancistrus subvirdis are both L200 also known as green phantoms. Hemiancistrus subvirdis is likely the same species as L128 although that is a topic for another day. One species can have multiple L numbers, which don’t always describe populations or all of the morphological variation of the species e.g. Baryancistrus xanthellus has 4 L numbers.

To top it off there are fake L numbers, L600 for example described Pseudacanthicus leopardus who already has the L numbers, L114 and L427. The L number system is only up to around 530 species so far. The letters added to L numbers aren’t a part of the L number system and increase confusion. Sometimes species are given by the hobby the L number of an entirely different species such as L144 which doesn’t even exist in the hobby and hasn’t done for decades or L056 for Parancistrus aurantiacus when actually that L number refers to an undescribed brown Pseudancistrus.

There is additionally the LDA number system which does overlap slightly but isn’t so expansive.

Introduction

Loricariidae, pleco’s are the largest family within the order of fishes known as Siluriforme also known as catfishes or welse, representing 1050 currently described species (Fricke et al., 2024). This group is exclusive to South and Central American freshwaters although has invasive populations in many continents.

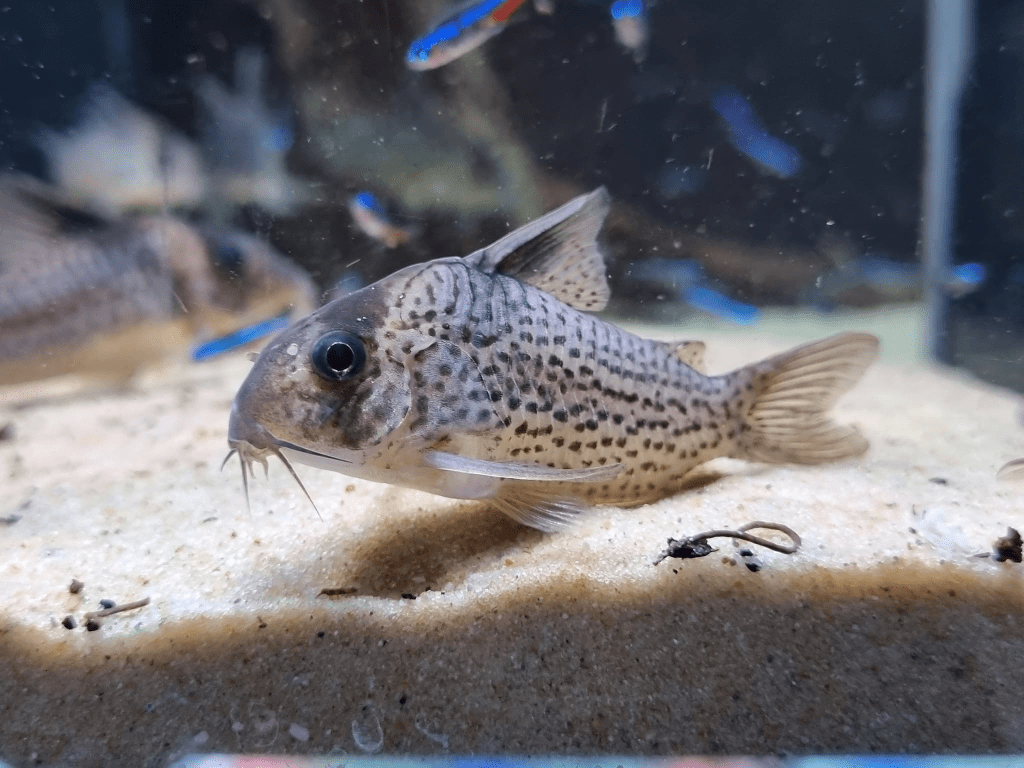

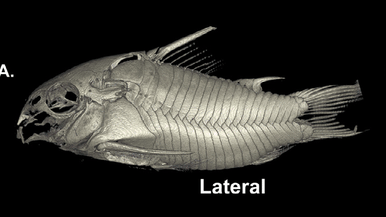

The family is identified by a downwards (ventrally) facing oral disc shaped mouth, in some species this is more of a suction cup whereas others they cannot attach to surfaces well or at all. This trait isn’t exclusive to Loricariids but it is not quite the same in other groups. Further more, Loricariids are defined by having a body covered in bony scutes, more scientifically known as dermal plating, not scales as catfishes lack scales.

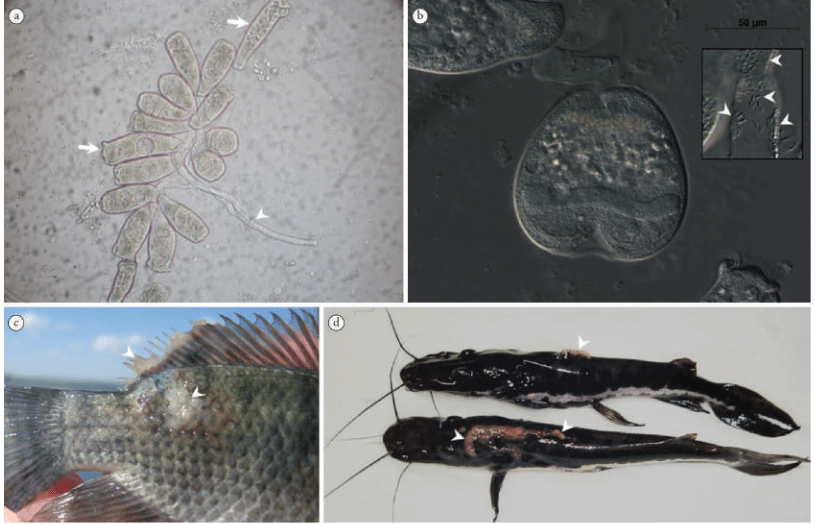

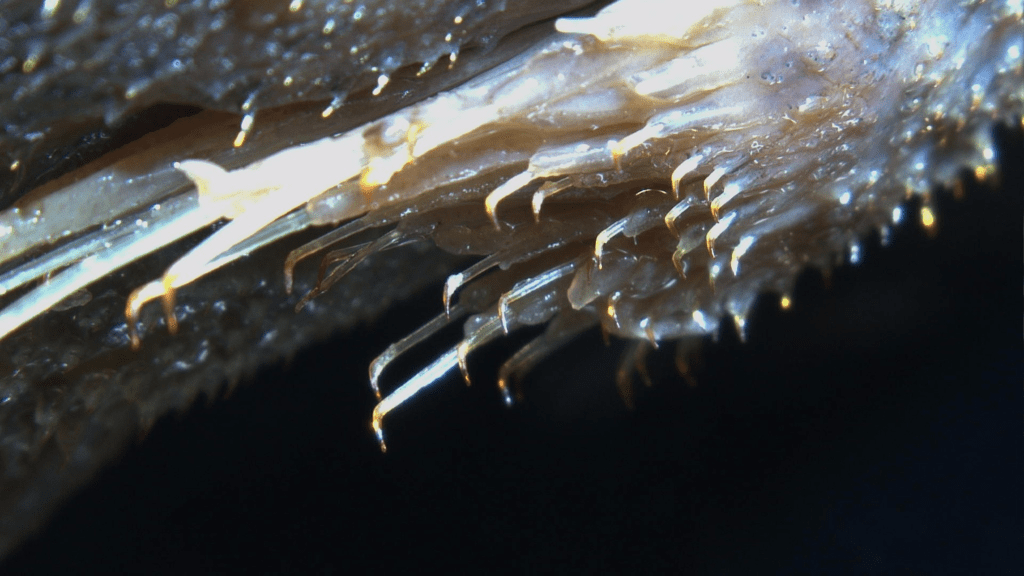

Not does Loricariidae just have dermal plating but they have spines known as odontodes, external teeth (Fig 2). Sometimes these are sexually dimorphic but not always, they can also be shed seasonally.

Loricariids realistically are one of the most morphologically diverse clades of fishes.

This diversity means that as a group, Loricariids are really difficult if impossible to generalize, research is paramount for this group.

The size of plecos

As one of the most diverse groups of fishes their size varies vastly, 0.2-0.8cm in Parotocinclus halbothi (Lehmann et al., 2014) to 100cm SL possibly in Acanthicus adonis. There is a wide diversity of sizes within many groups so there is no shortage of smaller and larger species. At the end of the article I will recommend reliable websites, there is frequent misleading information about the adult size of many species.

It is important to recognize reliable websites will use standard length, from the head to the base of the caudal/tail fin. That caudal/tail fin will be excluded as these can vary in length. I mention this as many people will not consider this measurement and forget their fish grows much bigger then they would originally consider. This is explained in detail in this article.

What should I feed my pleco?

This topic has the majority of misconceptions about Loricariids, the majority are algivores or detritivores (Lujan et al., 2012) but a wide range of diets are utilized. I have written a range of articles on a wide variety of diets across the family: Hypancistrus (zebra, king tigers, queen arabesque, snowball pleco, L236 etc.), Panaque and Panaqolus (royal pleco’s, flash pleco and the clown pleco’s), substrate dwelling Loricariinae (Pseudohemiodon, Planiloricaria etc.), Baryancistrus (gold nugget pleco, mango/magnum pleco, snowball pleco), mollusc specialists (Scobinancistrus, goldie/sunshine pleco, vampire pleco, galaxy pleco, Leporacanthicus), Chaetostoma (Rubbernoses and one of the bulldog plecos) and finally algivores/detritivores.

There are a few myths regarding Loricariid diets I will summerise:

- Pleco’s are largely carnivores, there are plenty of papers discussing their diets and while I wont cite them all Lujan et al. (2015) summerises it well.

- Pleco’s become carnivorous with age, there isn’t any studies regarding change in diet as the fishes age. Unlike most fishes, the majority of Loricariids break down their food before it enters their mouth, so the size of the fish doesn’t limit their food item, so not gape limited. This means unlike many other fishes their food item doesn’t need to change with size.

- Pleco’s clean a tank, while the majority are algivores and detritivores (Lujan et al., 2015) there is a wide diversity in niche partitioning (Lujan et al., 2011) and therefore those algivore’s specialize in certain algae’s. These algae’s seem not to be those that are an issue in the aquarium. Given their lifespan and waste production, they could be an expensive solution to high nutrients.

- Pleco’s don’t eat cyanobacteria, they actually don’t just eat those that are pests in the aquarium, in the wild they feed on cyanobacteria (Valencia & Zamudio ,2007).

Always check the ingredients as some diets that claim to contain algae’s might contain anything from none to 5%.

Do pleco’s need wood?

This is discussed in more detail here: Panaque and Panaqolus (royal pleco’s, flash pleco and the clown pleco’s).

In simple NO, they do not need wood. The only species that utilize wood are in the genera Panaque, Panaqolus, Hypostomus cochliodon group, Pseudoqolus and perhaps Lasiancistrus heteracanthicus. These groups all share unique spoon shaped teeth they can gouge into wood and if found among wood, wood is found in their gut (Lujan et al., 2017). No other Loricariid has wood in their gut, I’ve scoured gut records but they simply don’t have the jaws or teeth to gouge into wood. There have been many studies to confirm these fishes do not eat/digest the wood (Watts et al., 2021; German, 2009), instead they are just evolved to feed on biofilms, like other species from where other species cannot access, within wood (Lujan et al., 2011).

What parameters do pleco’s need?

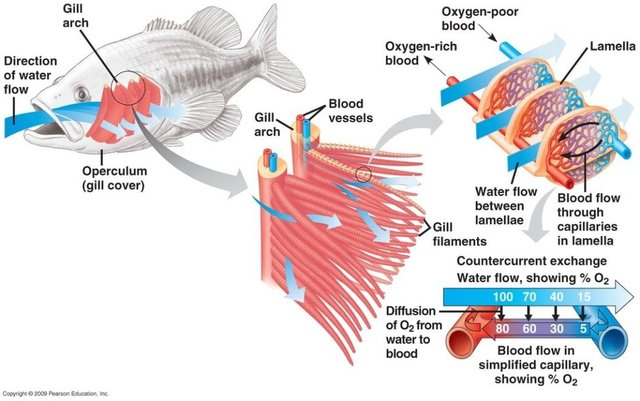

While the general idea is that Loricariids and in general anything South America requires soft, low conductivity and acidic water there is a wide diversity of parameters. Some species are found in lower temperatures while other much higher, 28c or higher (Collins et al., 2015; Urbano‐Bonilla & Ballen et al., 2021). Other misconceptions are that South American habitats have a lot of leaf litter and is black water, this is completely untrue, there are many different habitat types (Bogotá-Gregory et al., 2020). In general the majority of Loricariidae are rheophilic and would benefit from a current within the aquarium although there is some diversity (Krings et al., 2023). In general any current within the aquarium is a lot weaker then any of the weaker streams in their wild range.

Planet Catfish has really accessible information to identify parameters before looking into the scientific literature.

What decor do plecos require?

This is largely the only consistent aspect of Loricariids. If anyone has kept Loricariids they will know how much they like cracks, crevices, hiding spaces, rocks, branches and in general cover. There are many caves and tunnels on the market designed for the preferences of a variety of species. I recommend stacking up wood or rocks in a careful way so nothing falls but this will create many more caves.

Tankmates

This will always be based on experience and understanding of the fishes. It’s important to recognize a few key things about Loricariids.

- Loricariids do not often feed rapidly but even if they do it can take them minutes to an hour to reach food. Fast feeding fishes such as most cichlids, loaches, tetra, livebearers and goldfish particularly in large numbers are a bad idea.

- Their temperature might not overlap.

- They will need a current, some more then others which this means they wont work with fishes like long finned Betta splendens.

- While some Loricariids feed on food items that they wouldn’t naturally it doesn’t mean it is good for them. Bloat can happen in some genera more then others. So I do not recommend keeping other fishes with Loricariids who you plan on feeding anything like beefheart.

- Hardness, conductivity etc. We don’t actually know the KH or GH of the water many of these fishes come from, usually we have conductivity and pH records for many waters. Ideally these fishes are ill-suited regardless with Rift Valley cichlids, generally the biggest issue is above, those cichlids feed way too rapidly for any Loricariid.

Recommended websites

References:

Collins, R. A., Ribeiro, E. D., Machado, V. N., Hrbek, T., & Farias, I. P. (2015). A preliminary inventory of the catfishes of the lower Rio Nhamundá, Brazil (Ostariophysi, Siluriformes). Biodiversity Data Journal, (3).

Bogotá-Gregory, J. D., Lima, F. C., Correa, S. B., Silva-Oliveira, C., Jenkins, D. G., Ribeiro, F. R., … & Crampton, W. G. (2020). Biogeochemical water type influences community composition, species richness, and biomass in megadiverse Amazonian fish assemblages. Scientific Reports, 10(1), 15349.

Fricke, R., Eschmeyer, W. N. & Van der Laan, R. 2024. ESCHMEYER’S CATALOG OF FISHES: GENERA, SPECIES, REFERENCES. (http://researcharchive.calacademy.org/research/ichthyology/catalog/fishcatmain.asp). Electronic version accessed 22 July 2024.

German, D. P. (2009). Inside the guts of wood-eating catfishes: can they digest wood?. Journal of Comparative Physiology B, 179, 1011-1023.

Krings, W., Konn-Vetterlein, D., Hausdorf, B., & Gorb, S. N. (2023). Holding in the stream: convergent evolution of suckermouth structures in Loricariidae (Siluriformes). Frontiers in Zoology, 20(1), 37.

Lehmann, P. A., Lazzarotto, H., & Reis, R. E. (2014). Parotocinclus halbothi, a new species of small armored catfish (Loricariidae: Hypoptopomatinae), from the Trombetas and Marowijne River basins, in Brazil and Suriname. Neotropical Ichthyology, 12, 27-33.

Lujan, N. K., Cramer, C. A., Covain, R., Fisch-Muller, S., & López-Fernández, H. (2017). Multilocus molecular phylogeny of the ornamental wood-eating catfishes (Siluriformes, Loricariidae, Panaqolus and Panaque) reveals undescribed diversity and parapatric clades. Molecular phylogenetics and evolution, 109, 321-336.

Lujan, N. K., German, D. P., & Winemiller, K. O. (2011). Do wood‐grazing fishes partition their niche?: morphological and isotopic evidence for trophic segregation in Neotropical Loricariidae. Functional Ecology, 25(6), 1327-1338.

Lujan, N. K., Winemiller, K. O., & Armbruster, J. W. (2012). Trophic diversity in the evolution and community assembly of loricariid catfishes. BMC Evolutionary Biology, 12, 1-13.

Roxo, F. F., Ochoa, L. E., Sabaj, M. H., Lujan, N. K., Covain, R., Silva, G. S., … & Oliveira, C. (2019). Phylogenomic reappraisal of the Neotropical catfish family Loricariidae (Teleostei: Siluriformes) using ultraconserved elements. Molecular phylogenetics and evolution, 135, 148-165.

Urbano‐Bonilla, A., & Ballen, G. A. (2021). A new species of Chaetostoma (Siluriformes: Loricariidae) from the Orinoco basin with comments on Amazonian species of the genus in Colombia. Journal of Fish Biology, 98(4), 1091-1104.

Valencia, César Román, and Héctor Zamudio. 2007. Dieta y reproducción de Lasiancistrus caucanus (Pisces: Loricariidae) en la cuenca del río La Vieja, Alto Cauca, Colombia. Revista del Museo Argentino de Ciencias Naturales nueva serie 9(2): 95-101.

Watts, J. E., McDonald, R. C., & Schreier, H. J. (2021). Wood degradation by Panaque nigrolineatus, a neotropical catfish: diversity and activity of gastrointestinal tract lignocellulolytic and nitrogen fixing communities. In Advances in Botanical Research (Vol. 99, pp. 209-238). Academic Press.