Choosing fish foods can be very confusing, there are many products on the market all with various claims. The majority of fish diets are formulated based on the nutrition for food fishes, these diets have an aim to have a high growth rate while minimizing costs, efficiency would be the best term. The aim of the ornamental aquarist is far from that, we want a long lived healthy fish with good coloration. The nutritional composition requirements are differ between the two aims (Vucko et al., 2017). This has resulted in many diets not catering for the aim of the fishkeeper and no where is this more obvious then diets aimed at plecos, Loricariids.

- Catering for Algivores/detritivores.

- Catering for Carnivores.

- Other niches and specialization.

- Will they eat it?

- Premade diets and their ingredients

- The hidden issue with premade diets

- Products sold for plecos

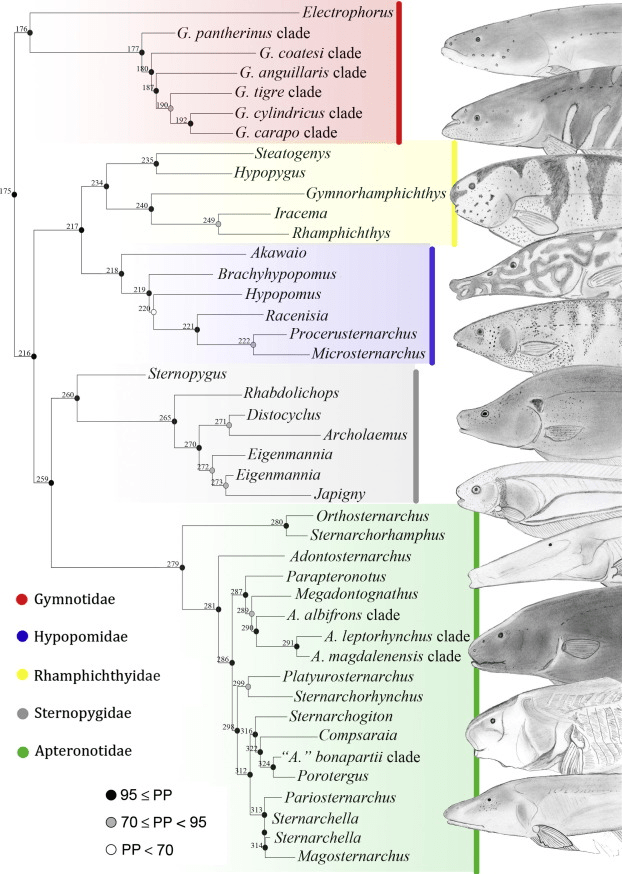

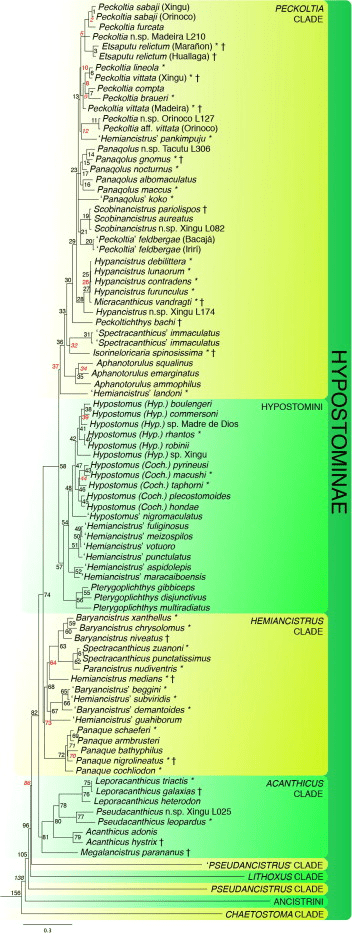

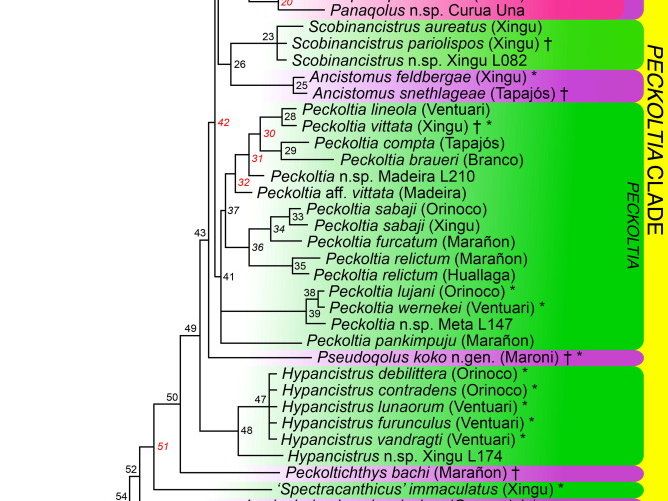

The majority of Loricariids are algivores or detritivores, but there is a diversity of dietary niches (Lujan et al., 2015). Contrastingly many products labelled as pleco or algae wafers/pellets contain little to no algae but higher proportions of fish meal (Vucko et al., 2017). The majority of popular Loricariids are along the lines of algivory or feed on various volumes so this should be a focus for the aquarist. Additionally I have yet to see fish ever recorded in the gut of any Loricariid.

Catering for Algivores/detritivores.

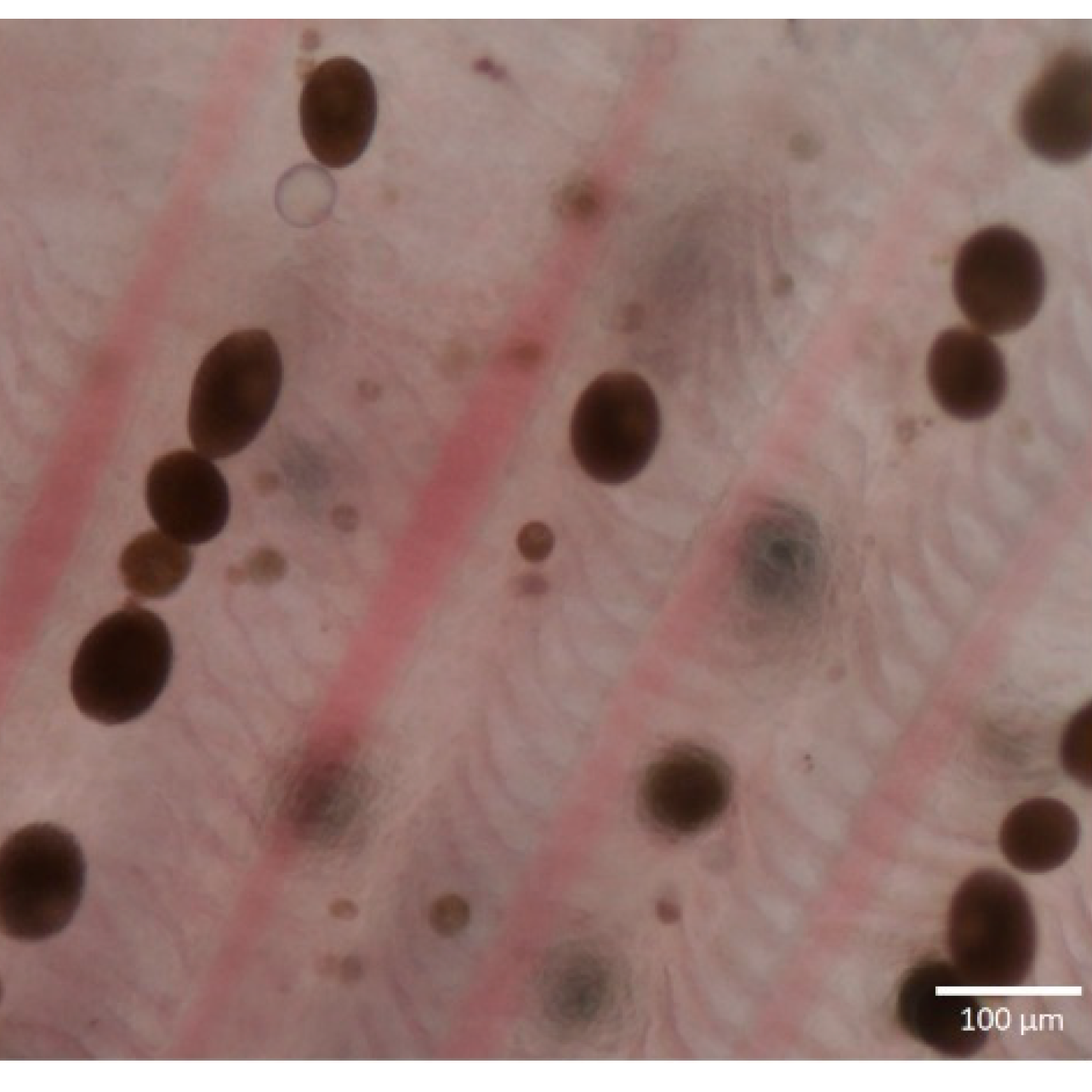

I have written quite a bit about this niche and therefore I recommend reading this article here which covers details into algivory, detritivory and wood eating.

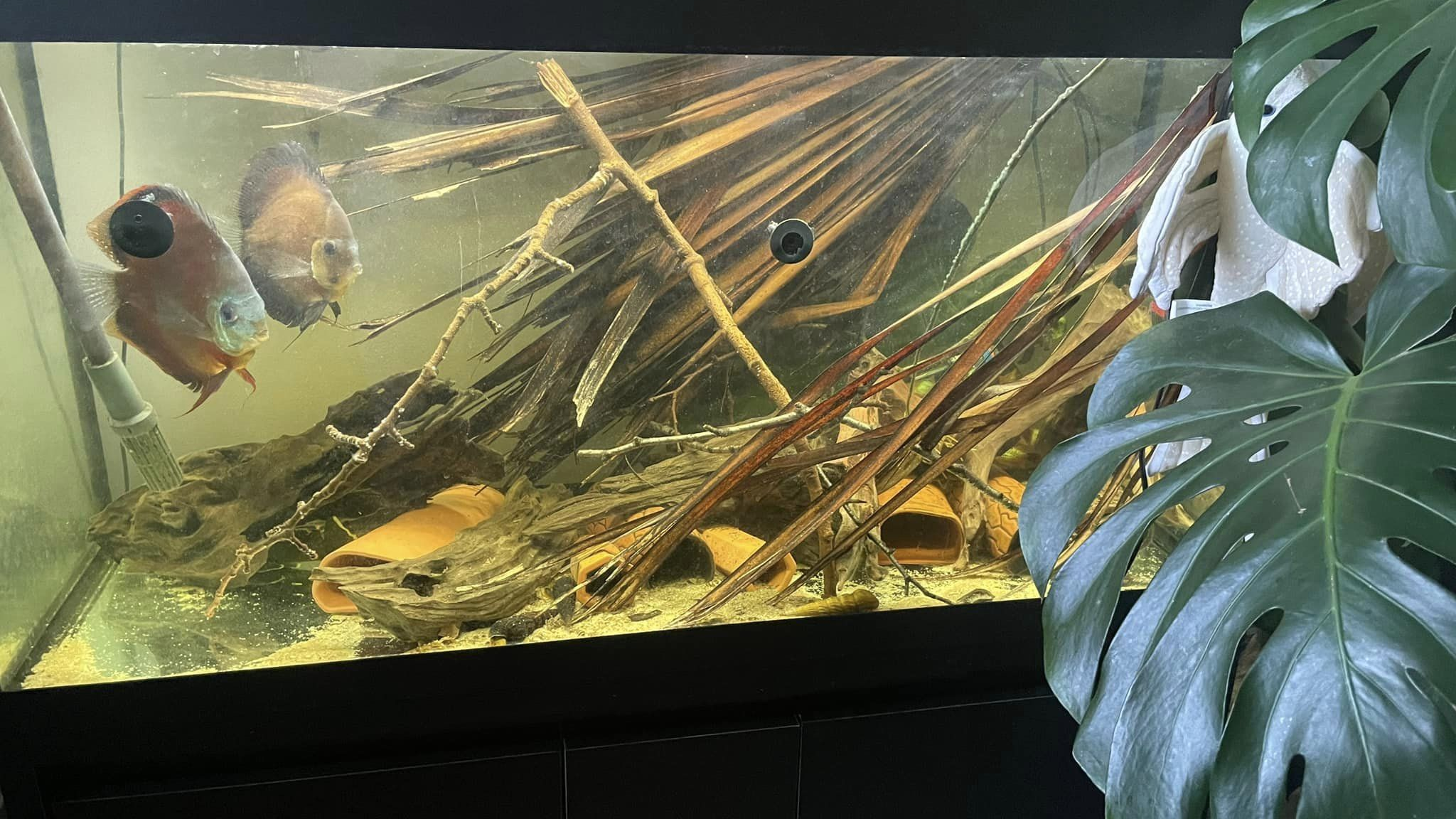

These fishes are the most difficult to cater for giving there isn’t quite the selection of algaes available in any diet. Some of them can be difficult for the fish to take to so hence I find Repashy soilent green good and can then be bulked out with even more algae’s.

Catering for Carnivores.

I am not really discussing carnivores so much in this article as there are many diets that cater for them and in recent years with the focus into invertebrates it is only improving. Still, many diets are very high in fish meals, something Loricariids do not consume and nutritionally these do not compare. Not just can fish meals be different nutritionally, the nutrients can be difficult to access (Žák et al., 2022).

There is a little diversity of carnivory within Loricariidae but we don’t entirely know to what extent. I have written this article for mollusc specialists and although diverse in diets this for dwell in and around the substrate.

The great thing for carnivores is the diversity of frozen foods we have available within the hobby and even fishmongers. Although keep aware for the enzyme thiaminase (in mussels and some fishes) and limit the frequency these are fed to your fishes.

Other niches and specialization.

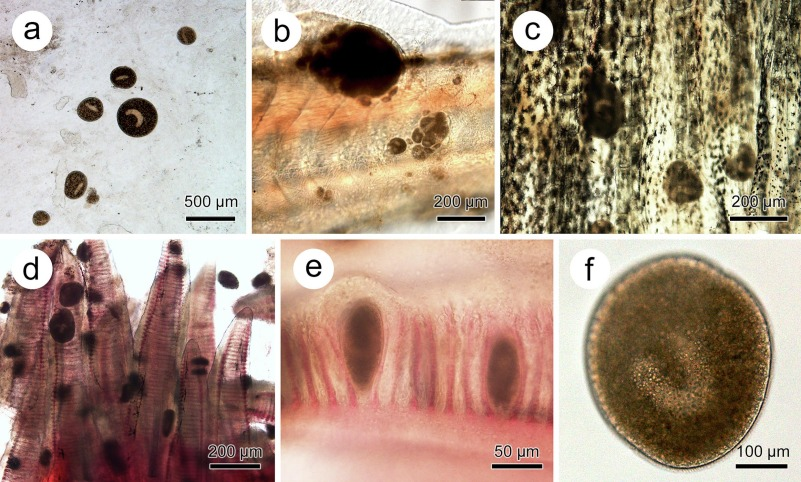

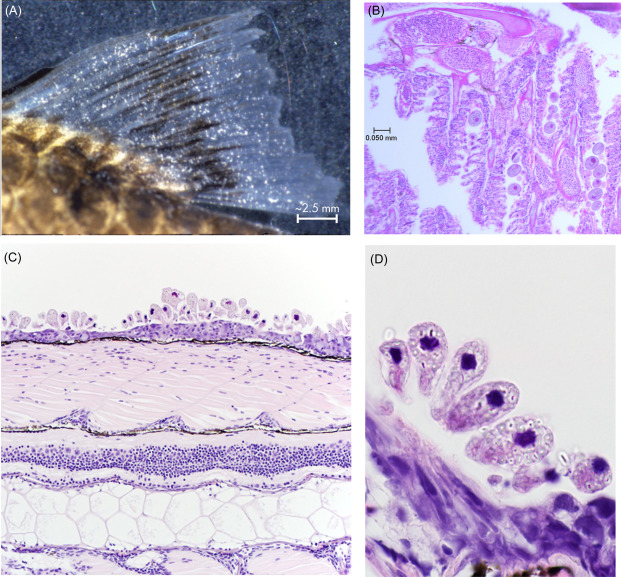

Fungi hyphae are found in the diets of Panaque, Panaqolus and the Hypostomus cochliodon group and are likely digested, mushrooms or mycoproteins would be the closest to replicating this (Lujan et al., 2011). Sadly most diets don’t contain these. It would be interesting to feed wood that has many of these but usually by the point they have obvious hyphae they are almost entirely broken down.

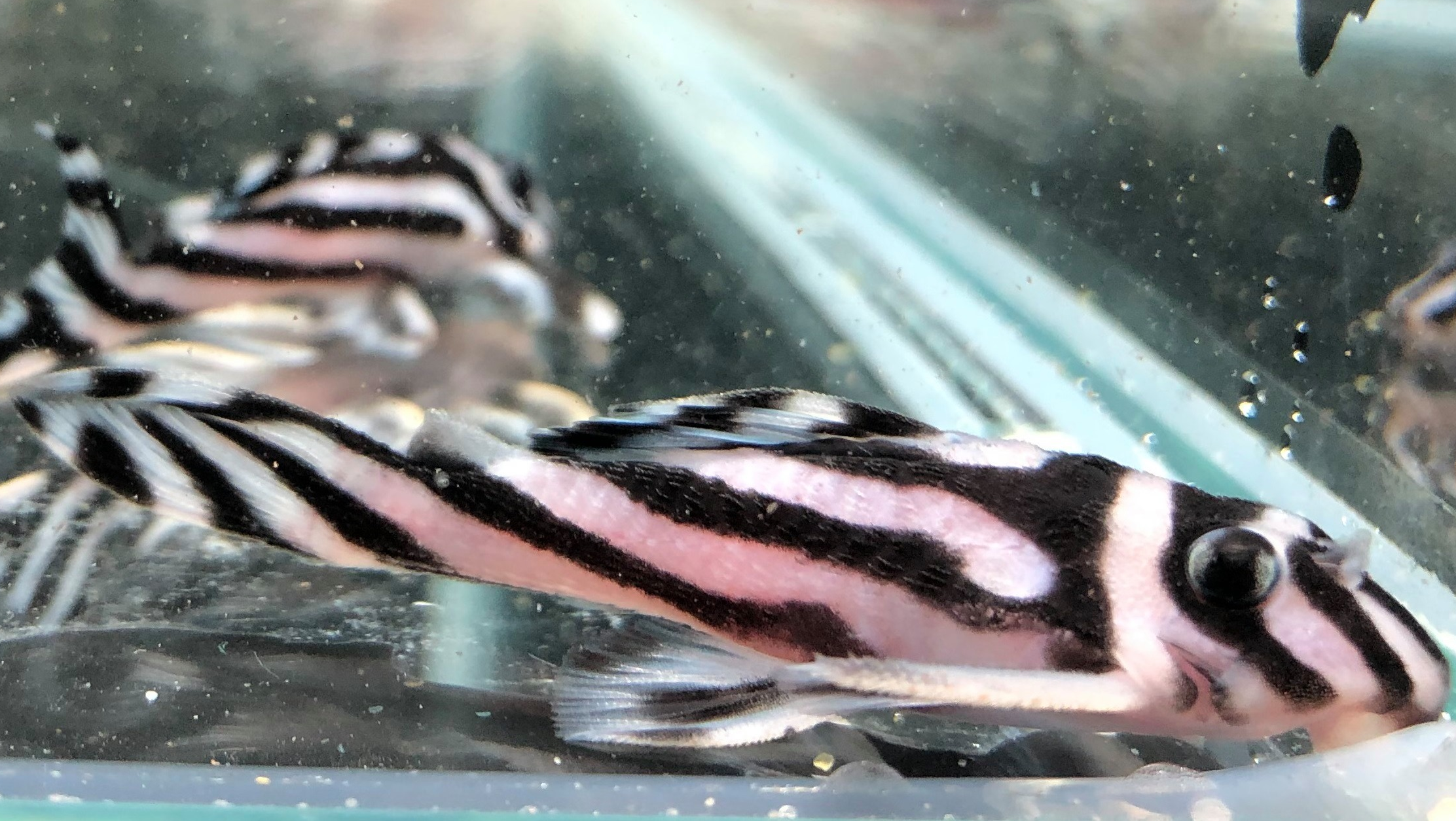

While Hypancistrus are largely algivores, there is evidence a few of them feed on seeds, read about Hypancistrus here. The exception being Hypancistrus vandragti who seems a little more carnivorous in comparison (Lujan & Armbruster, 2011).

Will they eat it?

Something few consider is that just because a diet might be amazing with ingredients they might not eat it. So there are a range of ingredients such as some herbs used entirely to encourage fishes to eat a diet. This has been the issue I’ve found with some that have great ingredients Repashy super green for example.

Premade diets and their ingredients

Premade diets unlike if you were to make anything yourself entirely will have a reasonable range of nutrients. They are best more as a basis to work from for a more well rounded diet.

From these tables it is easy to understand the varying suitability of different diets to different species and genera. The colour coding is only to give an idea as many ingredients have multiple purposes e.g. fish meal can be a binding agent as well as for nutrition.

Ingredients are ordered in quantity so the top of the list contributes the most.

The hidden issue with premade diets

There is a hidden issue, as you look across the table how similar are many of these diets? Many fishkeepers will buy a range of different products in the aim of diversity of nutrition and ingredients. If so many of the ingredients and the orders are similar this means that there is little diversity, the exception would be there the major ingredients are very different.

Products sold for plecos

| Company | Repashy | |||

| Product | Soilent Green | Super Green | Bottom scratcher | Morning wood |

| Dietary Niche | Algivory | Algivory | Carnivory | Xylovory |

| Summary | Fishes tend to prefer this diet. Contains mostly algae but has a some animal meals but can be bulked out with more algae’s. | Contains no animal products. Fish seem less keen on it. High in algae’s. | Contains a diversity of invertebrates. Shouldn’t be fed as the only diet for non-carnivores as can lead to bloat e.g. Hypancistrus. | No Loricariids digest wood, cellulose is the main ingredient. |

| Composition (%): | ||||

| Protein | 40 | 35 | 45 | 20 |

| Fat | 8 | 8 | 10 | 3 |

| Fibre | 8 | 8 | 12 | 50 |

| Moisture | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 |

| Ash | 12 | 9 | 11 | 15 |

| Ingredients | ||||

| Spirulina Algae, Algae Meal (Chlorella), Krill Meal, Pea Protein Isolate, Squid Meal, Rice Protein Concentrate, Fish Meal, Alfalfa Leaf Meal, Dried Brewer’s Yeast, Coconut Meal, Stabilized Rice Bran, Flax Seed Meal, Schizochytrium Algae, Dried Seaweed Meal, Lecithin, Dried Kelp, Locust Bean Gum, Potassium Citrate, Taurine, Stinging Nettle, Garlic, RoseHips, Hibiscus Flower, Calendula Flower, Marigold Flower, Paprika, Turmeric, Salt, Calcium Propionate and Potassium Sorbate (as preservatives), Magnesium Amino Acid Chelate, Zinc Methionine Hydroxy Analogue Chelate, Manganese Methionine Hydroxy Analogue Chelate, Copper Methionine Hydroxy Analogue Chelate, Selenium Yeast. Vitamins: (Vitamin A Supplement, Vitamin D Supplement, Choline Chloride, Calcium L-Ascorbyl-2-Monophosphate, Vitamin E Supplement, Niacin, Beta Carotene, Pantothenic Acid, Riboflavin, Pyridoxine Hydrochloride, Thiamine Mononitrate, Folic Acid, Biotin, Vitamin B-12 Supplement, Menadione Sodium Bisulfite Complex). | Spirulina Algae, Algae Meal (Chlorella), Pea Protein Isolate, Rice Protein Concentrate, Alfalfa Leaf Powder, Stabalized Rice Bran, Dandelion Powder, Dried Brewer’s Yeast, Coconut Meal, Ground Flaxseed, Schizochytrium Algae, Dried Seaweed Meal, Dried Kelp, Locust Bean Gum, Lecithin, Potassium Citrate, Taurine, Stinging Nettle, Garlic, RoseHips, Hibiscus Flower, Calendula Flower, Marigold Flower, Paprika, Turmeric, Calcium Propionate and Potassium Sorbate (as preservatives), Magnesium Amino Acid Chelate, Zinc Methionine Hydroxy Analogue Chelate, Manganese Methionine Hydroxy Analogue Chelate, Copper Methionine Hydroxy Analogue Chelate, Selenium Yeast. Vitamins: (Vitamin A Supplement, Vitamin D Supplement, Choline Chloride, Calcium L-Ascorbyl-2- Monophosphate, Vitamin E Supplement, Niacin, Beta Carotene, Pantothenic Acid, Riboflavin, Pyridoxine Hydrochloride, Thiamine Mononitrate, Folic Acid, Biotin, Vitamin B-12 Supplement, Menadione Sodium Bisulfite Complex). | Krill Meal, Insect Meal, Mussel Meal, Squid Meal, Dried Brewer’s Yeast, Dried Seaweed Meal, Lecithin, Dried Kelp, Locust Bean Gum, Potassium Citrate, Taurine, Watermelon, RoseHips, Hibiscus Flower, Calendula Flower, Marigold Flower, Paprika, Turmeric, Stinging Nettle, Garlic, Salt, Calcium Propionate and Potassium Sorbate (as preservatives), Magnesium Amino Acid Chelate, Zinc Methionine Hydroxy Analogue Chelate, Manganese Methionine Hydroxy Analogue Chelate, Copper Methionine Hydroxy Analogue Chelate, Selenium Yeast. Vitamins: (Vitamin A Supplement, Vitamin D3 Supplement, Choline Chloride, Calcium L-Ascorbyl-2-Monophosphate, Vitamin E Supplement, Niacin, Beta Carotene, Pantothenic Acid, Riboflavin, Pyridoxine Hydrochloride, Thiamine Mononitrate, Folic Acid, Biotin, Vitamin B-12 Supplement, Menadione Sodium Bisulfite Complex). | Cellulose Powder, Dried Seaweed Meal, Alfalfa Leaf Meal, Spirulina Algae, Rice Protein Concentrate, Pea Protein Isolate, Stabilized Rice Bran, Dried Brewer’s Yeast, Dried Kelp, Stinging Nettle, Locust Bean Gum, Calcium Carbonate, Potassium Citrate, Malic Acid, Taurine, Garlic, Watermelon, RoseHips, Hibiscus Flower, Calendula Flower, Marigold Flower, Paprika, Turmeric, Salt, Calcium Propionate and Potassium Sorbate (as preservatives), Magnesium Amino Acid Chelate, Zinc Methionine Hydroxy Analogue Chelate, Manganese Methionine Hydroxy Analogue Chelate, Copper Methionine Hydroxy Analogue Chelate, Selenium Yeast. Vitamins: (Vitamin A Supplement, Vitamin D Supplement, Choline Chloride, Calcium L-Ascorbyl-2-Monophosphate, Vitamin E Supplement, Niacin, Beta Carotene, Pantothenic Acid, Riboflavin, Pyridoxine Hydrochloride, Thiamine Mononitrate, Folic Acid, Biotin, Vitamin B-12 Supplement, Menadione Sodium Bisulfite Complex). |

Repashy unlike the other brands is a gel diet, this means other products such as algae powders can be added in. This means for any of them you can increase the algal composition or add ingredients such as basil.

| Company | Fluval | AquaCare | ||

| Product | Bug Bites Pleco Sticks | Bug Bites Pleco Crisps | Spirulina Sinking Wafers | Oak |

| Dietary Niche | Carnivore | Omnivore/cereals | Omnivore | Omnivore/cereals |

| Summary | A reasonable amount of insects so more ideal then those with more fish meals for carnivores. | A smaller amount of insect meals and contains a wider range of cereals. | Mostly fish meal with a lot of cereals, little algae. | Loricariids cannot digest wood/cellulose nor is it used for digestion. Mostly wheat, which will have limited nutrition and a high amount of fish meal. |

| Composition (%): | ||||

| Protein | 32 | 43.5 | 43.7 | 38.3 |

| Fat | 12 | 4 | 5.7 | 3.7 |

| Fibre | 6 | 3 | 3 | 3.2 |

| Moisture | ? | ? | 7.1 | 9 |

| Ash | 9 | 5 | 10.5 | 13.4 |

| Ingredients | ||||

| Black soldier fly larvae (30%), salmon (22%), wheat, peas, potato, dicalcium phosphate, alfalfa nutrient concentrate, calcium carbonate, calendula, rosemary. | Insect Meal (Mealworm Meal 15%, Black Soldier Fly Larvae 10%), Wheat flour, Wheat Gluten, Wheat germ, Alfalfa, Spirulina, Fish Protein Hydrolyzed, Kelp (5%), Shrimp Protein Hydrolyzed, Spinach (5%), Activated Charcoal. | Fish meal, Wheat, Wheat Gluten, Mycoprotein, Shrimp, Spirulina, Alfa-Alfa, Salmon Oil, Wheat germ, Spinach, Vitamins, Minerals | Wheat, Herring Meal, Wheatgerm, Spirulina, Alfalfa, Kelp, Oak Bark, Zeolite, Minerals, Vitamins |

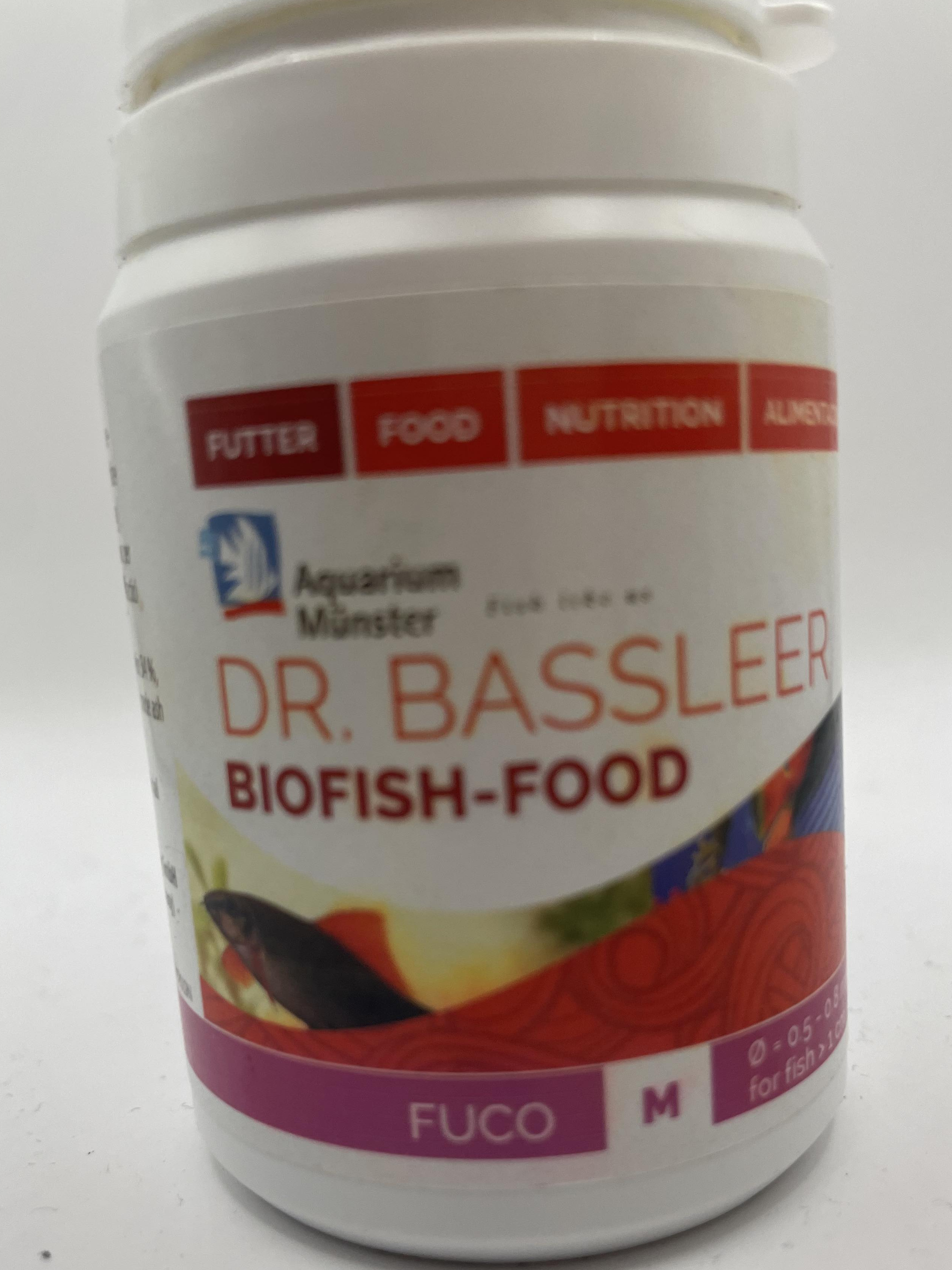

| Company | Hikari | Dr Bassler | Vitalis | |

| Product | Algae Wafers | Green | Regular | Pleco Pellets |

| Dietary Niche | Omnivore | Omnivore | Omnivore | Omnivore |

| Summary | Not ideal. Contains a lot of fish meal and cereals. A general diet that targets no species. | Very high in cereals and fish meals. Too few algaes to cater for an algivore. | Pretty much the same as the green diet. A lot of fish meal and cereals. | Not ideal. A very general diet that doesn’t cater for any species. Mostly contains fish. |

| Composition (%): | ||||

| Protein | 33 | 57 | 54 | 39.4 |

| Fat | 4 | 18 | 16 | 7 |

| Fibre | 3 | 2 | 4 | 1.5 |

| Moisture | 10 | ? | 6 | 25 |

| Ash | 17 | 10 | 10 | 17.3 |

| Ingredients | ||||

| Fish meal, wheat flour, wheat germ meal, cassava starch, dried bakery product, dried seaweed meal, alfalfa nutrient concentrate dehydrated, dehydrated alfalfa meal, brewers dried yeast, soybean meal, fish oil, krill meal, spirulina, garlic. | Cereals, fish and fish derivatives, derivatives of vegetable origin, Chlorella pyrenoidosa (5 %), Moringa oleifera (5 %), molluscs and crustaceans, yeast, minerals Additives: Vitamins: E672 Vitamin A 7,500 IE/kg, E671 Vitamin D3 2,500 IE/kg , E300 Vitamin C 500 mg/kg, E307 Vitamin E 260 mg/kg, Magnesium 400 mg/kg, Iron 300 mg/kg, Omega-3 fatty acids 50 mg/g, Vitamin B3 7.5 mg/kg, Chlorophyll 2 mg/kg, Folic acid 2 mg/kg, Selenium 1 mg/kg, Iodine 0.02 mg/kg | Fish and fish derivatives, cereals, molluscs and crustaceans, derivatives of vegetable origin, yeast, minerals Additives: Vitamins: E672 vitamin A 7500 IU/kg, E671 vitamin D3 2500 IU/kg, E300 vitamin C 500 mg/kg, E307 vitamin E 260 mg/kg | Fish and Fish Derivatives, Derivatives of Vegetable Origin, Algae, Oils and Fats, Minerals, Molluscs and Crustaceans. |

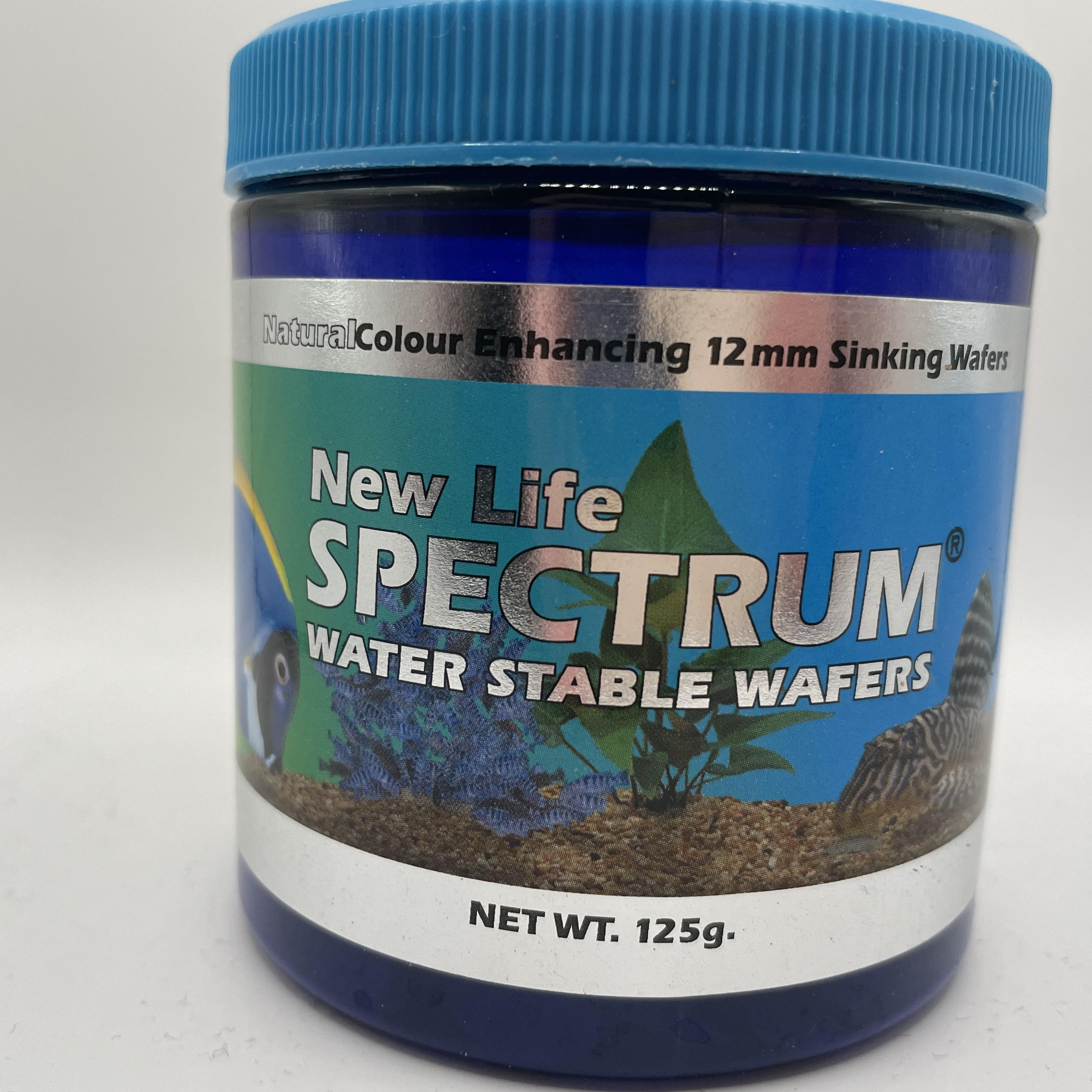

| Company | Oase | Tetra | New Life Spectrum | Fish Science |

| Product | Organix Veggievore Tabs | Spirulina Wafers | Algae Max | Algae wafers |

| Dietary Niche | Carnivore | Herbivore | Algivore | Omnivore |

| Summary | A lot of fish/shrimp meals. Only a small amount of krill. | Plant focused but lacks a lot of algaes. | Beware some have higher fish meal volumes. Otherwise a great range of algaes. | Would benefit from more algaes, the use of mycoproteins is interesting but still a large amount of cereals and fish meal. |

| Composition (%): | ||||

| Protein | 35 | 28 | 34 | 42 |

| Fat | 13 | 6 | 8 | 7.5 |

| Fibre | 1 | 5 | 8 | 2.2 |

| Moisture | ? | 9 | 10 | 10 |

| Ash | 9 | ? | ? | 8.5 |

| Ingredients | ||||

| Whole Salmon, Whole Shrimp, Wheat Flour, Kelp, Whole Herring, Wheat Germ, Vitamins and Minerals. | Cereals, Vegetable protein extracts, Derivatives of vegetable origin, Yeasts, Oils and fats, Algae (Ascophyllum Nodosum 3,0%, Spirulina 0,9 %), Minerals. Vitamins: Vitamin D3 1810 IU/kg. Trace elements: Manganese (manganese (II) sulphate, monohydrate) 81 mg/kg, Zinc (zinc sulphate, monohydrate) 48 mg/kg, Iron (iron(II) sulphate, monohydrate) 32 mg/kg. Colourants, Preservatives, Antioxidants. | Seaweed (Ulva latuca, Undaria pinnatafida, Eucheuma cottonii, Eucheuma spinosum, Chondrus crispus, Porphyra umbilicus), Krill (Euphasia superba), Squid (Dosidicus gigas), Whole Wheat Flour, Kelp, Spirulina, Fish (Brevoortia tyrannus), Fish Oil, Garlic, Ginger, Astaxanthin, Marigold, Bentonite Clay, Sea Salt, Vitamin A Acetate,Vitamin D Supplement,Vitamin E Supplement, Vitamin B12 Supplement,Niacin, Folic Acid, Biotin, Thiamine Hydrochloride, Riboflavin Supplement, Pyridoxine Hydrochloride, Calcium Pantothenate, L-Ascorbyl-2-Polyphosphate (Vitamin C), Choline, Chloride, Ethylenediamine Dihydroiodide, Cobalt Sulfate, Ferrous Sulfate, Manganese Sulfate, Tocopherols (a preservative). | Algae (Spirulina & Kelp 15%), Mycoprotein, Cereals, Herring meal, Vegetable protein extracts, Insect meal, Vegetables (Cucumber, Spinach), Molluscs and crustaceans, Yeast, Salmon oil and Garlic. |

References:

Lujan, N. K., & Armbruster, J. W. (2011). Two new genera and species of Ancistrini (Siluriformes: Loricariidae) from the western Guiana Shield. Copeia, 2011(2), 216-225.

Lujan, N. K., German, D. P., & Winemiller, K. O. (2011). Do wood‐grazing fishes partition their niche?: morphological and isotopic evidence for trophic segregation in Neotropical Loricariidae. Functional Ecology, 25(6), 1327-1338.

Lujan, N. K., Winemiller, K. O., & Armbruster, J. W. (2012). Trophic diversity in the evolution and community assembly of loricariid catfishes. BMC Evolutionary Biology, 12, 1-13.

Vucko, M. J., Cole, A. J., Moorhead, J. A., Pit, J., & de Nys, R. (2017). The freshwater macroalga Oedogonium intermedium can meet the nutritional requirements of the herbivorous fish Ancistrus cirrhosus. Algal research, 27, 21-31.

Žák, J., Roy, K., Dyková, I., Mráz, J., & Reichard, M. (2022). Starter feed for carnivorous species as a practical replacement of bloodworms for a vertebrate model organism in ageing, the turquoise killifish Nothobranchius furzeri. Journal of Fish Biology, 100(4), 894-908.

| Company | ||||

| Product | ||||

| Dietary Niche | ||||

| Summary | ||||

| Composition (%): | ||||

| Protein | ||||

| Fat | ||||

| Fibre | ||||

| Moisture | ||||

| Ash | ||||

| Ingredients | ||||