Hybridisation is such a trigger word these days with many opinions for and against. First there are two definitions required:

Hybridisation: Interbreeding between two members of different species (Adah et al., 2013).

Crossbreeding: Interbreeding between two members of the same species, they might be the same variety/breed/cultivar or different.

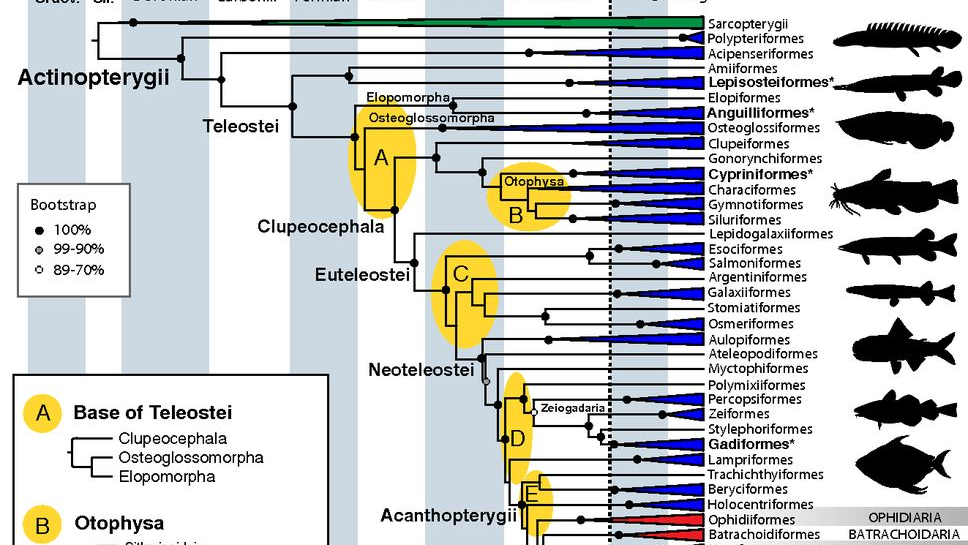

These two terms are often used interchangeably even if they do not refer to the same event. Although these terms are different they do rely on the definition of species, genera and higher taxa which is hotly debated. One frequent definition being the biological species definition which relies on hybridisation being a barrier although is largely unreliable (Mallet, 2001).

Hybridisation as an event is not uncommon (Scribner et al., 2000), the event (or events) has resulted in the development of new species, a process known as speciation (Litsios & Salamin, 2014). Not all of the offspring might be fertile, many people in the aquarium trade might be familiar with the hybrid parrot cichlids (Amphilophus citrinellus x. Heros efasciatus), this may be the biggest barrier to speciation.

Barriers to Hybridisation

There are many barriers to hybridisation which really can effect the result if there is some compatibility.

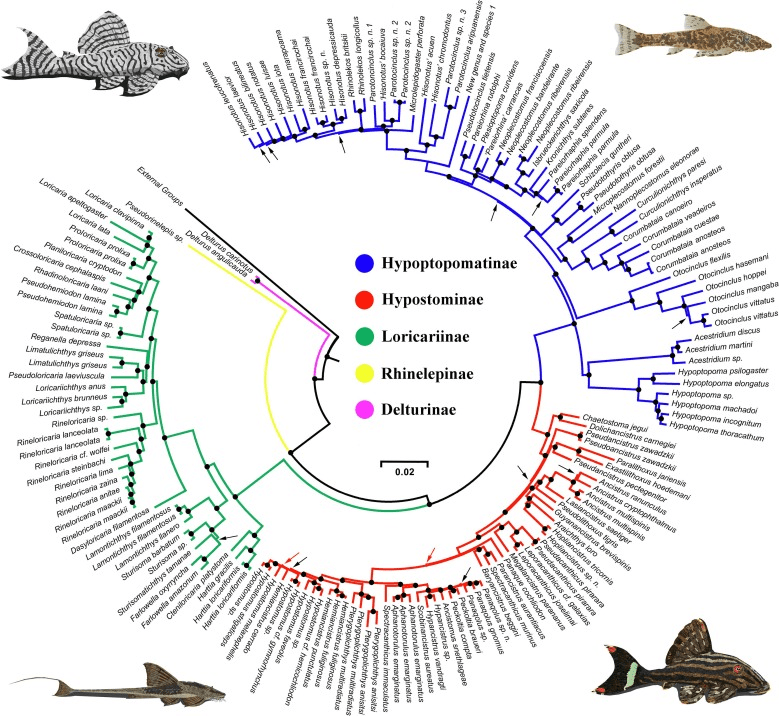

Chromosomal number is the most well known barrier to hybridisation, chromosomes are units within the nucleus that contains all the DNA. Most humans have 22 pairs, fruit flies, Drosophila melanogaster have 4 pairs and the duckbilled platyplus has 26 (a lot of sex chromosomes though!), chromosomal number does not infer complexity at all and nor does the size of a genome. Generally different species might have a different number of chromosomes, this is very well displayed in the Loricariid (pleco) genus, Ancistrus (bristlenoses) which displays a diversity of different chromosomal numbers across a 50 or more species large grouping (Santos da Silva et al., 2022). During reproduction parental chromosome numbers ideally need to match to put simply. While this is a barrier it has resulted in infertile offspring, or in the example of the livebearers from Poecilidae a number of unusual adaptations. These hybrid Poecilidae have the ability to reproduce via gynogensis, asexual reproduction with the requirement of a male to stimulate the process, he contributes nothing to the offspring (Schultz, 1969) and this is displayed potentially in many species originating from hybridisation (Turner, 1980). The limitations of chromosomes really vary though but are definitely present.

Morphology is one of the obvious but so easily forgotten, organisms have to be morphologically compatible not just for the initial act but additionally for fertilisation and gestation. It might not seem it but that minor differences in morphology make a difference, what might seem obscure such as the shape of spermatozoa can differ resulting in the cell not being able to imbed into the egg, it’s even so diverse that the morphology of this cell can infer groups (Quagio-Grassiotto et al., 2020). Species often judge each other via their morphology and therefore there is some level of sameness particularly in the wild.

Behaviour, different species or even different populations might display very different behaviours. Behaviour itself is so integral to reproduction and mate choice, outside of captivity this is such a strong barrier.

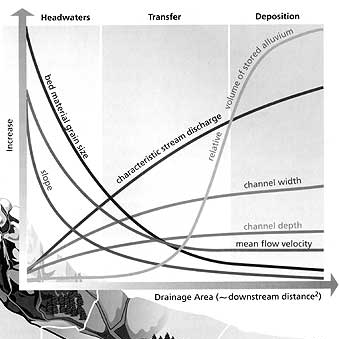

Geography is maybe the most well known barrier and often can result in the other divisions. This can be within a small space such as fishes which inhabit deeper water whereas others the shallows. Barriers don’t always have to be spatial but they can also be temporal.

The issues with hybridisation

Hybridisation itself is not negative it’s just a force, in terms of conservation it can provide a variety of effects. Hybridisation can lead to the decline in a population of a species, most well known in the case of the Scottish wildcat (Felis silvestris silvestris) and the sister species, the domestic cat (Felis catus). As hybrids display what is known as a hybrid vigour (a mixture of traits between the two pariental species) it can change how these individuals interact with their environment and the genetic diversity of a species (Selz & Seehausen, 2019). The ecological impact of the introduction of hybrids can be described as unpredictable (Mandeville et al., 2022) which makes it difficult to identify those exact issues. Although, this argument is similar to introducing individuals who are selectively bred who might also influence the gene pool of wild individuals. It is generally not ideal, hybridisation in conservation is reserved for restoring species where no other alternative can be found e.g. Prezewalski’s horse (Equus ferus prezewalskii) and the domestic horse (Equus ferus caballus) in an effort to save the subspecies, although hybridisation is a risk to the subspecies (King, 2005).

But here we are talking about captivity, it’s highly unlikely any of our fishes will be involved in any real conservation effort or practices.

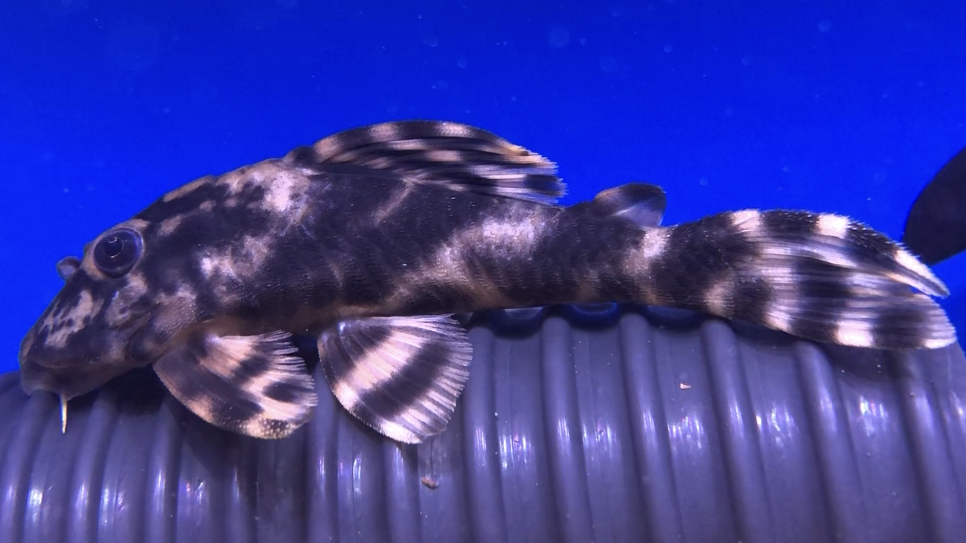

The main issue in captivity with these hybrids is so many do not go recorded, likely due to misidentifications of the parent species and lack of record keeping. Take Ancistrus dolichopterus, this species is generally diagnosed as having 8-9 soft dorsal rays, only one small individual was spotted excluding brown spots on the abdomen. While no seams were mentioned (Kner, 1854) it is commonly stated they display these, as with many other Ancistrus these often do fade with time and I have been shown individuals from the type locality lacking these seams. There are many spotted Ancistrus and over time localities and important information on them are lost. It’s more then often that these seams are how the judgement is based on what species it is. The point I am getting to is how well do we know these species and how they are defined? We are relying here on hybridisation not being able to occur but it likely does because species are kept together who are not the same species but assumed the same. I generally would assume unless wild caught for morphologically indistinctive Ancistrus, they should probably be assumed hybrids. I have frequently seen even Ancistrus ranunculus, a morphologically distinctive Ancistrus be misidentified so it’s a difficult situation. This doesn’t include how little we know about some genera, the frequency of bycatch and misidentifications from suppliers as well.

Surely those who argue against hybridisation should also argue against crossing those from different localities or populations. This is also changing the genetic landscape of a population and asks the question of how to define a species.

In captivity it does effect if you are getting what you think you are getting but for many this might not be an issue. One of the biggest worries though is because hybrids are a pick and mix of the parental species morphology and behaviour is largely unknown, it could be more similar to one parent then the other, an intermediate or totally different. Where parental species have different requirements this is also an issue.

How to avoid hybridisation

For wild caught fishes maybe getting fishes from the same source and checking locality matches if you are not completely confident on the identification. Keep records of who is being crossed with who.

It’s quite simple to keep those who could maybe hybridised apart, this is difficult to judge as it is not just about genera but if it looks similar don’t keep them together. If hybridisation occurs clearly record that and any offspring should be sold labelled as such, if possible to pet only homes with no worries of breeding where that label can be forgotten over generations.

For captive bred individuals the situation is difficult, if you aren’t sure and they aren’t from a responsible or reliable source then don’t buy unless you plan on just having the animals as a pet, assuming you don’t want to increase the number of hybrids.

Hybridisation Bias

Much of the dislike towards hybrids is focused on certain species although hybrids are much more common then they seem. Fishes such as domestic discus (Symphysodon spp.) are a mixture of the three different species and definitely the different localities depending on the variety (Ng et al., 2021). Some domestic species might have hybrid origins such as the common bristlenose, Ancistrus sp. but we do not know. These species do not seem to have health related defects from their morphology although those such as the parrot cichlid, Amphilophus sp. x. Vieja sp. (not to be confused with the true parrot cichlid, Hoplarchus psittacus), clearly does have health related deformities as a result of selective breeding and hybridisation as displayed in this link to a Monster FishKeepers discussion forum.

Conclusion

Hybridisation will always occur in the hobby, it is best that it is labelled so future keepers are aware of what their fishes are. If you are not completely sure of the species you are keeping then don’t breed it, ideally anyone who can identify the species should be able to cite a reliable website or the description of the species. Undescribed species might not have this so should have more precautions made such as keeping to one locality and morphology.

References

Adah, P. M., Onyia, L. U., & Obande, R. A. (2013). Fish hybridization in some catfishes: A review.

King, S. R. (2005). Extinct in the Wild to Endangered: the history of Przewalski’s horse (Equus ferus przewalskii) and its future conservation. Mongolian Journal of Biological Sciences, 3(2), 37-41.

Kner, R. (1854). Die Hypostomiden: Zweite Hauptgruppe der Familie der Panzerfische.(Loricata vel Goniodontes) (Vol. 1). KK Hof-und Staatsdruckerei.

Litsios, G., & Salamin, N. (2014). Hybridisation and diversification in the adaptive radiation of clownfishes. BMC Evolutionary Biology, 14, 1-9.

Mallet, J. (2001). Species, concepts of. Encyclopedia of biodiversity, 5, 427-440.

Mandeville, E. G., Hall Jr, R. O., & Buerkle, C. A. (2022). Ecological outcomes of hybridization vary extensively in Catostomus fishes. Evolution, 76(11), 2697-2711.

Ng, T. T., Sung, Y. Y., Danish-Daniel, M., Sorgeloos, P., de Peer, Y. V., Wong, L. L., & Tan, M. P. (2021). Genetic variation of domesticated discus (Symphysodon spp.). Aquaculture, Aquarium, Conservation & Legislation, 14(2), 832-840.

Schultz, R. J. (1969). Hybridization, unisexuality, and polyploidy in the teleost Poeciliopsis (Poeciliidae) and other vertebrates. The American Naturalist, 103(934), 605-619.

Santos da Silva, K., Glugoski, L., Vicari, M. R., de Souza, A. C. P., Noronha, R. C. R., Pieczarka, J. C., & Nagamachi, C. Y. (2022). Chromosomal Diversification in Ancistrus Species (Siluriformes: Loricariidae) Inferred From Repetitive Sequence Analysis. Frontiers in Genetics, 13, 838462.

Scribner, K. T., Page, K. S., & Bartron, M. L. (2000). Hybridization in freshwater fishes: a review of case studies and cytonuclear methods of biological inference. Reviews in Fish Biology and Fisheries, 10, 293-323.

Selz, O. M., & Seehausen, O. (2019). Interspecific hybridization can generate functional novelty in cichlid fish. Proceedings of the Royal Society B, 286(1913), 20191621.

Turner, B. J., Brett, B. L. H., & Miller, R. R. (1980). Interspecific hybridization and the evolutionary origin of a gynogenetic fish, Poecilia formosa. Evolution, 34(5), 917-922.

Quagio-Grassiotto, I., Baicere-Silva, C. M., de Oliveira Santana, J. C., & Mirande, J. M. (2020). Spermiogenesis and sperm ultrastructure as sources of phylogenetic characters. The example of characid fishes (Teleostei: Characiformes). Zoologischer Anzeiger, 289, 77-86.