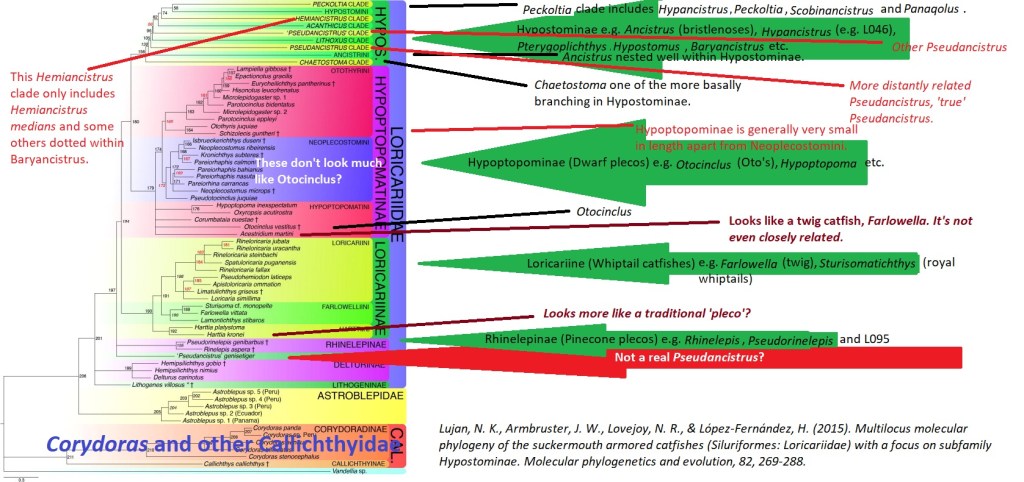

This is a big question when it comes to keeping Loricariids in the aquarium as more then often people want to spawn the fishes but sometimes people just want to name them.

What is the sex determination methods in Loricariidae?

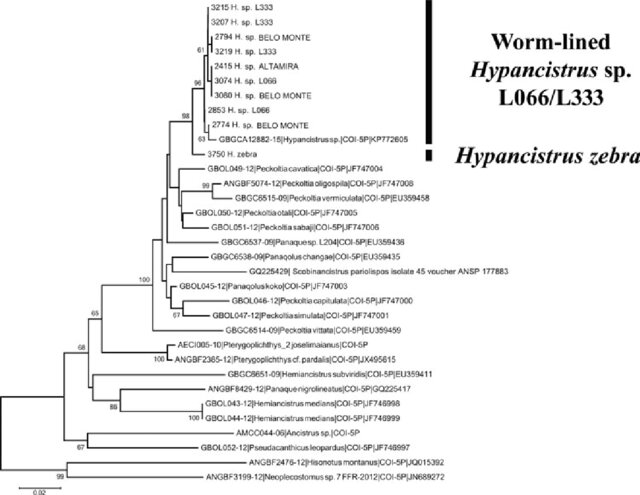

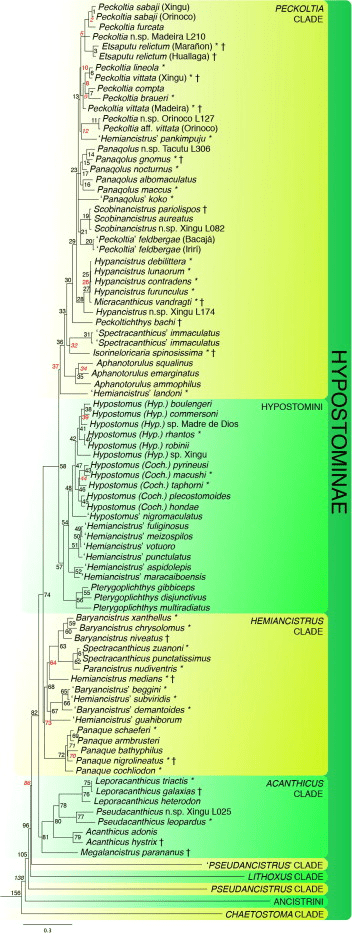

This is actually a more vast discussion then some other groups like mammals. In fact Loricariid’s use a range of karyotypes to determine sex from the more well known ZW and XY to multiple sex chromosomes. Ancistrus (Bristlenoses) is a large genus representing over 60 spp. (Eschmeyer, 2025), this genus does show multiple sex determination methods and some not as well known such as ZZ/ZW1W2 in Ancistrus clementinae (Nirchio et al., 2023) or ZZ/ZW in Ancistrus ranunculus (Oliveira et al., 2007). It seems many genera show a lot of diversity (Sassi et al., 2023) and this is possibly a large barrier to hybridization and maybe could lead to speciation.

What do you need to be able to identify the sex of your Loricariid?

- A mature fish, unless the fish has reached sexual maturity it likely wont show many sexually dimorphic features although there are slight exceptions at the smaller level or during dissection. Largely this will mean close to fully grown and/or clearer odontode growth. Some species this might take a year such as some of the more common Ancistrus or 5+ years like the Hemiancistrus medians group (e.g. Panaque, Baryancistrus etc.)

- A bowl, container or polybox can be useful to examine around the fish particularly below. Fill this with the tank water, do not do it during acclimation. It can be done in store.

Anatomy that allows you to sex Loricariids

Venting – Genital papilla and the urogenital pore

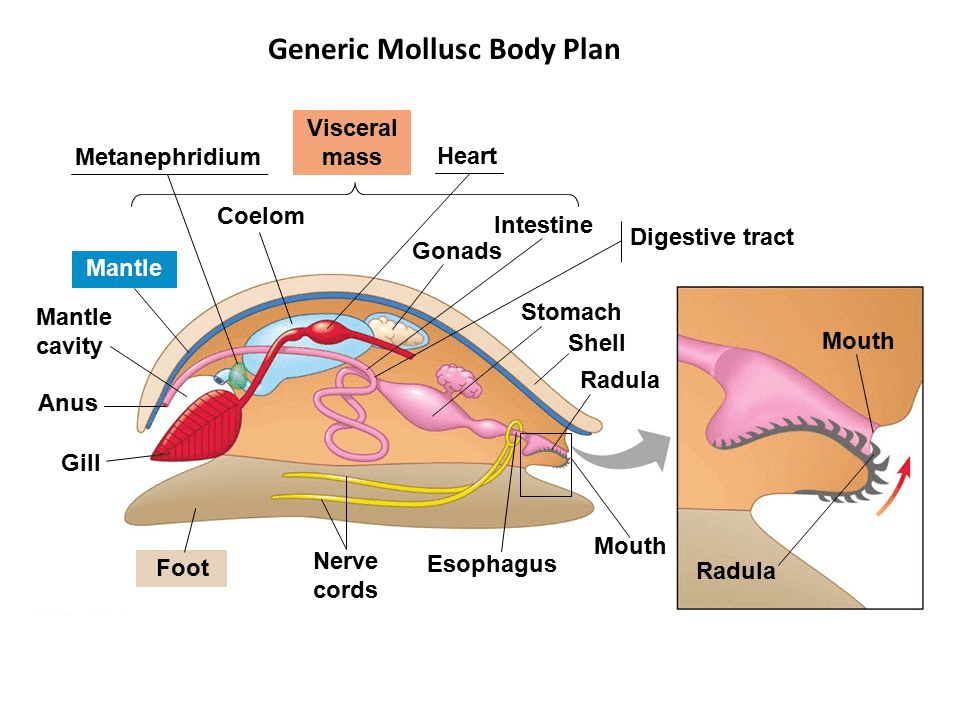

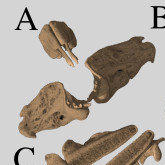

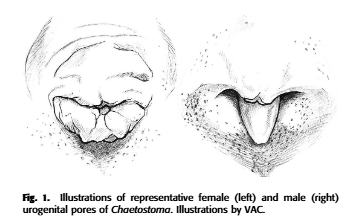

The genital papilla and the urogenital pore are the same thing, this is a combined organ where the fish passes waste but also the gametes (eggs and sperm). This is not the same for all Loricariids where the genital pore is separate from the anus such as in Neoplecostomus. It is clearly on the abdomen, shape is normally ambiguous in juveniles.

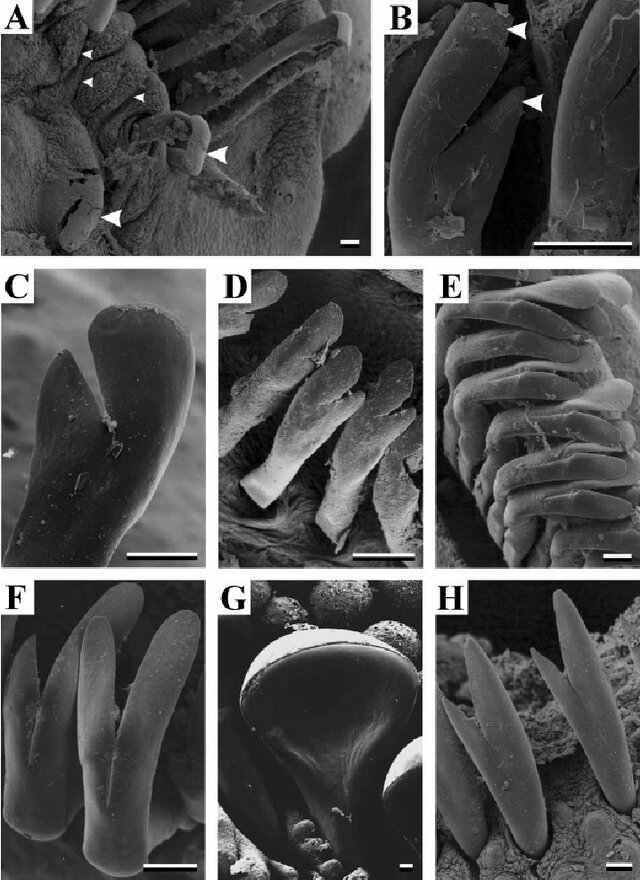

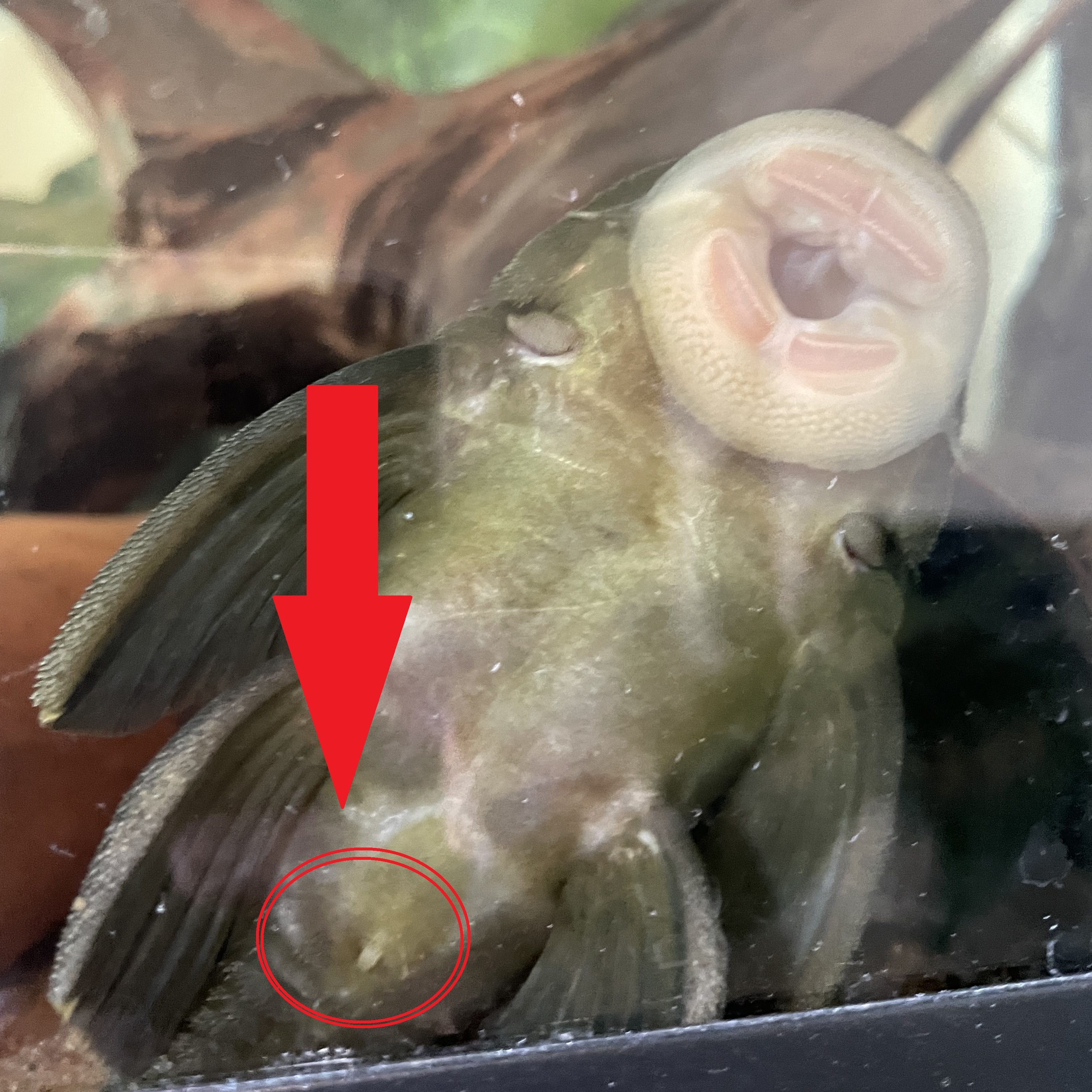

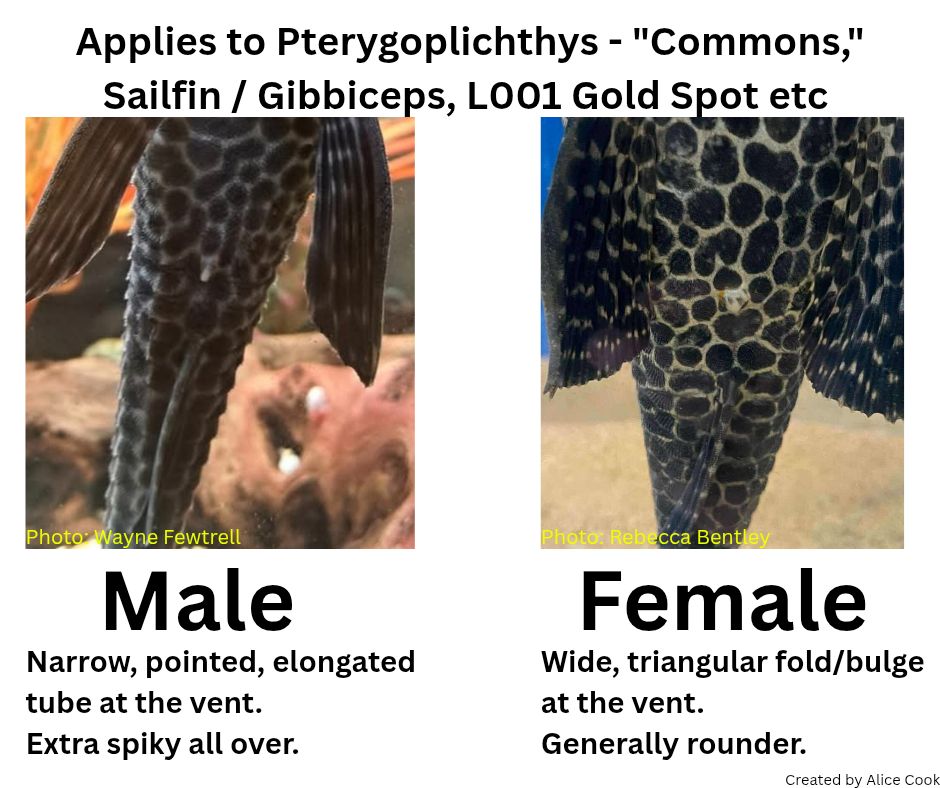

The shape of the genital papilla is the most reliable method to sex Lorcariids, it’s most easily stated as V shaped in males and U in females. This can be tricky to see in some genera which have more elongate genital papilla such as the Pterygoplichthys in figure 2.

Some other genera the females are much wider so it is much more square as above. The best method is to see multiple individuals and compare between them which can be done against the glass and taking photos or even within a container to take a more up close look.

I find this method the most reliable particularly as there is less individual variation between individuals and also depends less on the age of the fish. The shape can be applied also to Loricariinae (whiptail catfishes) and Hypoptopominae (Otocinclus, Parotocinclus, Hypoptopoma etc.).

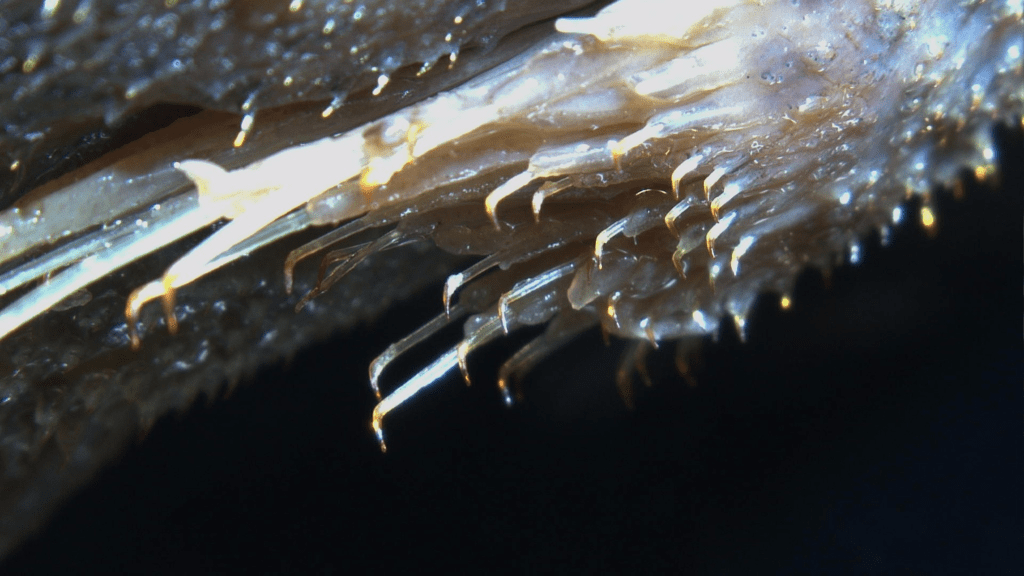

The final part of the genital papilla when it comes to sexing Loricariids is spotting around this region in females. These papilla/spots can be green or yellow in colour and can range from one to many in number, once visible to the eye it hints maturity in the females. While it is very obvious in Hypostominae (traditional pleco’s) it is unclear as to if these are present in the other subfamilies even the distantly related but similarly looking Pseudancistrus genisetiger (slate pleco’s) and Rhinelepinae. Although I have been told by Fauna Tropica (https://www.faunatropica.eu/) that these spots can be seen under a microscope and maybe a macrolens before maturity even as younger juveniles.

Body shape

I am not a massive fan of using body shape as it can depend on many factors. Using how plump the fish is does depend on how well the fish has been fed but also females once the female has released eggs can suddenly reduce weight.

Head shape does seem the most reliable method regarding the general anatomy but can be limited when it comes to stunted fish but there is also a lot of individual variation. In general it is assumed females display more elongate heads whereas males are shorter and wider, this is a trend we do see in other fishes.

Personally when it comes to sexing individuals from photos I am less of a fan of this method as it does rely even more on angle of the photo but also maturity. You can see a larger difference in some genera then others and some species you might not see it at all.

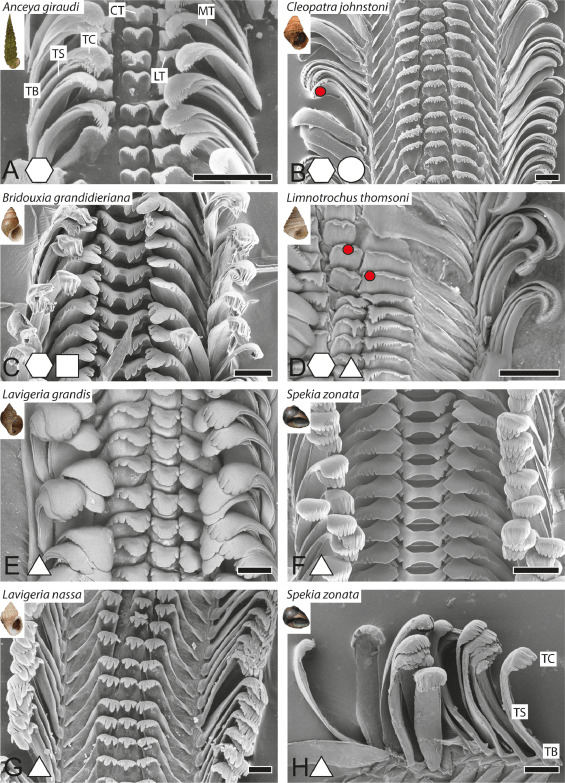

Odontodes

Odontodes are the external teeth that cover Loricariids, this does include everything from Otocinclus to Farlowella to Hypancistrus. In some species they can be enlarged in certain areas and this is known as hypertrophied, further in some these odontodes can be sexually dimorphic. Odontodes as a secondary sexual characteristic though are not a rule and there are many exceptions, in addition they can be seasonal so males might have reduced ones seasonally and females can have larger ones, it depends on the genus.

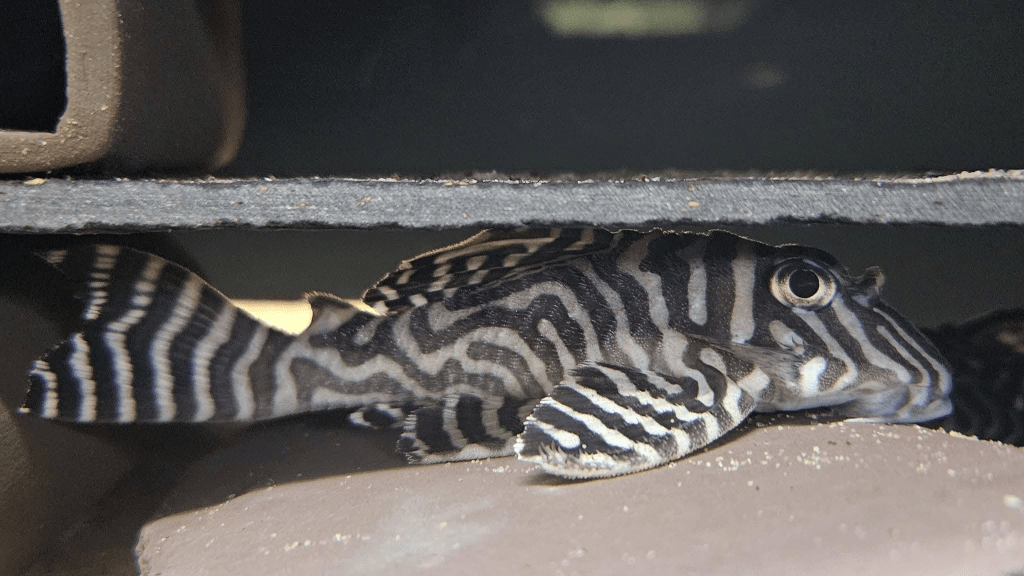

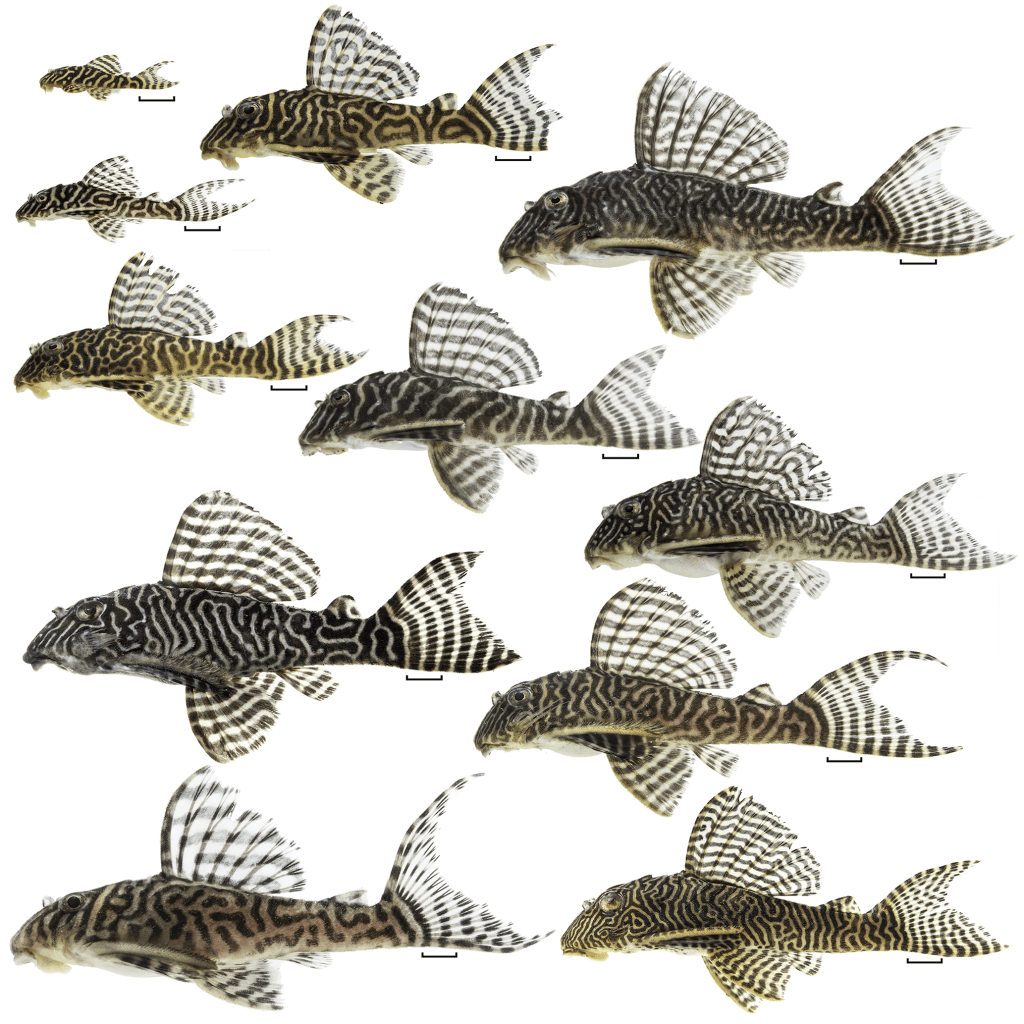

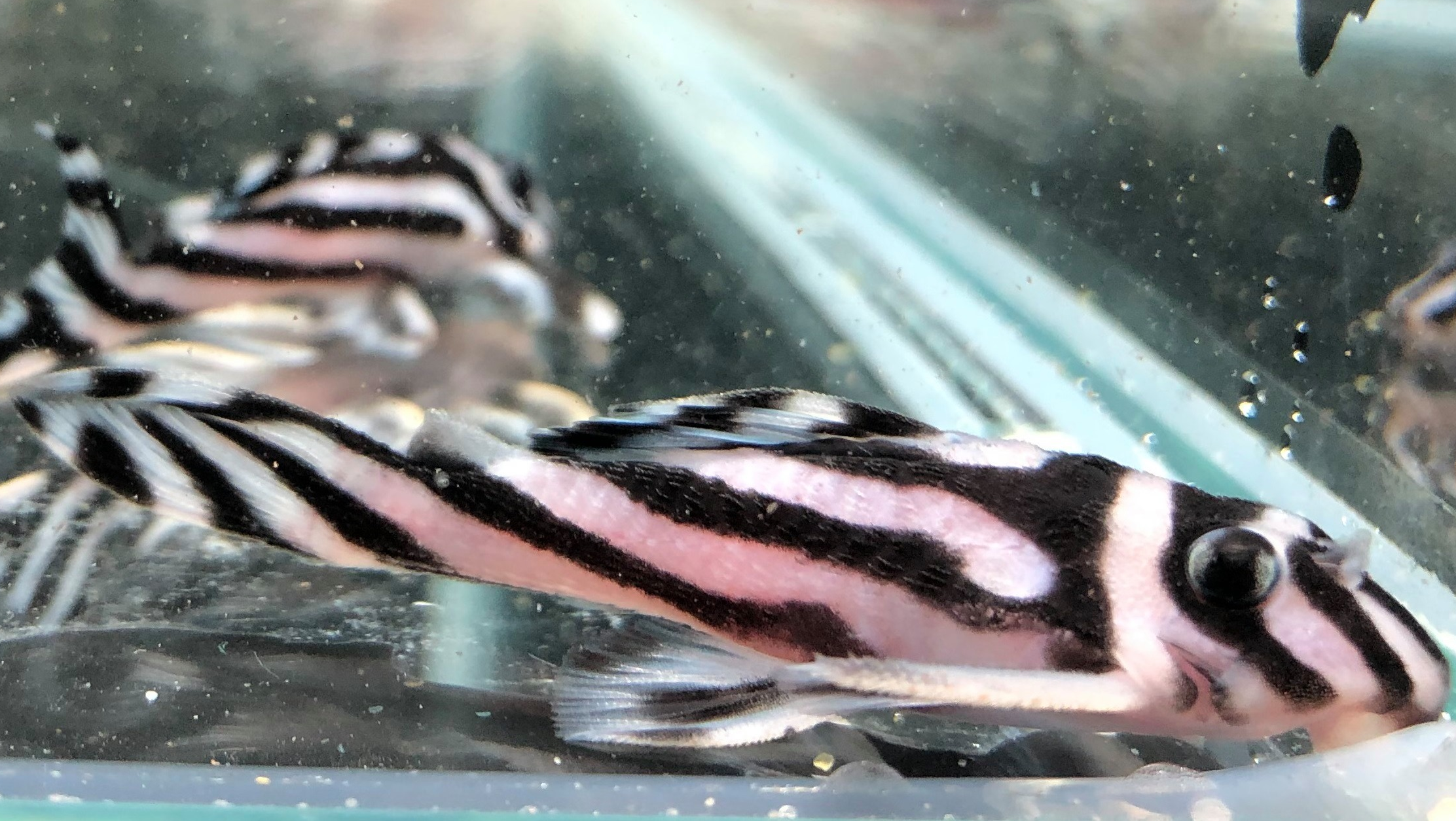

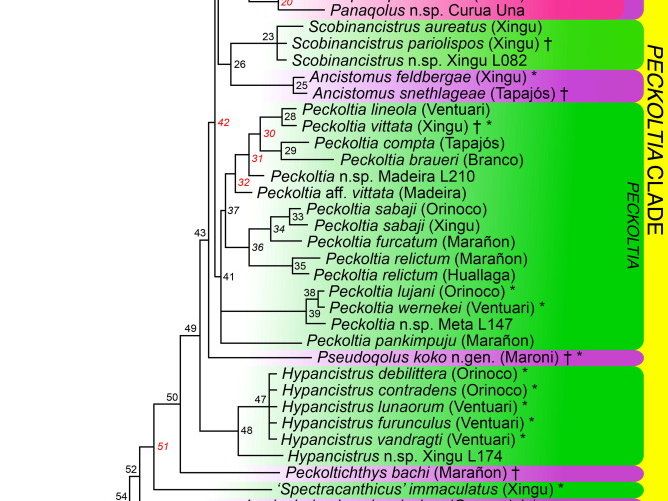

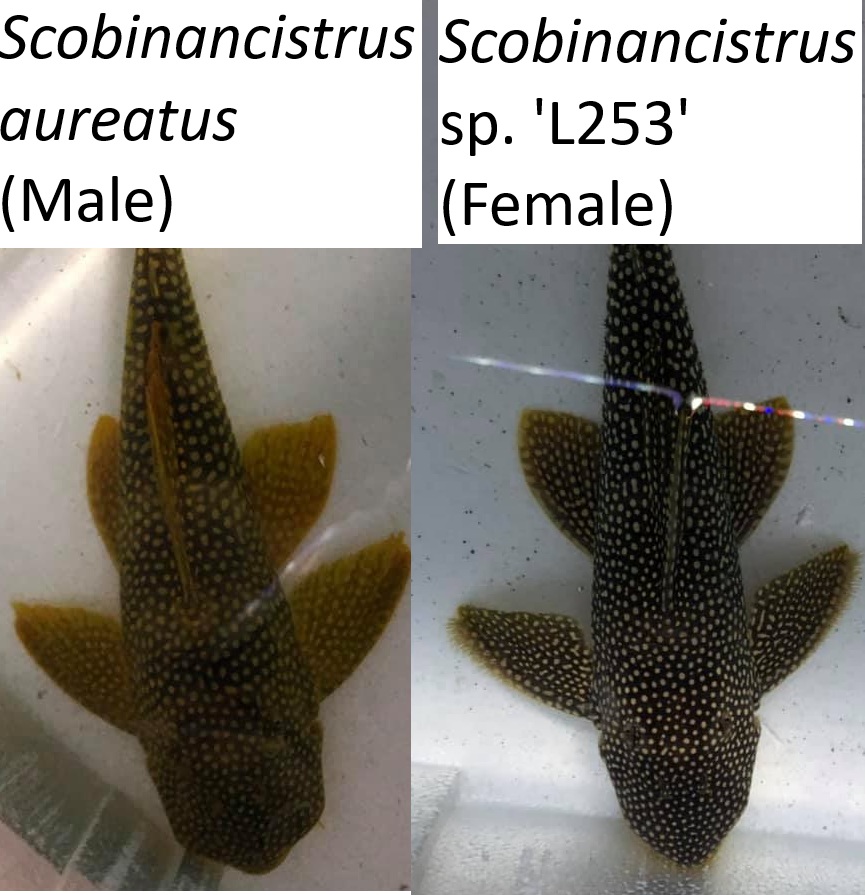

Odontodes are most useful in the Peckoltia clade, this includes Hypancistrus, Peckoltia, Panaqolus, Pseudoqolus, Ancistomus and Scobinancistrus. Although Scobinancistrus and species such as Peckoltia sabaji do not have particularly sexually dimorphic odontodes and I recommend using the genital papilla. These odontodes are hypertrophied in all individuals at the gill opercular although can be larger in males. The most obvious method with this clade is hypertrophied odontodes on the caudal peduncle and pectoral fin of the males.

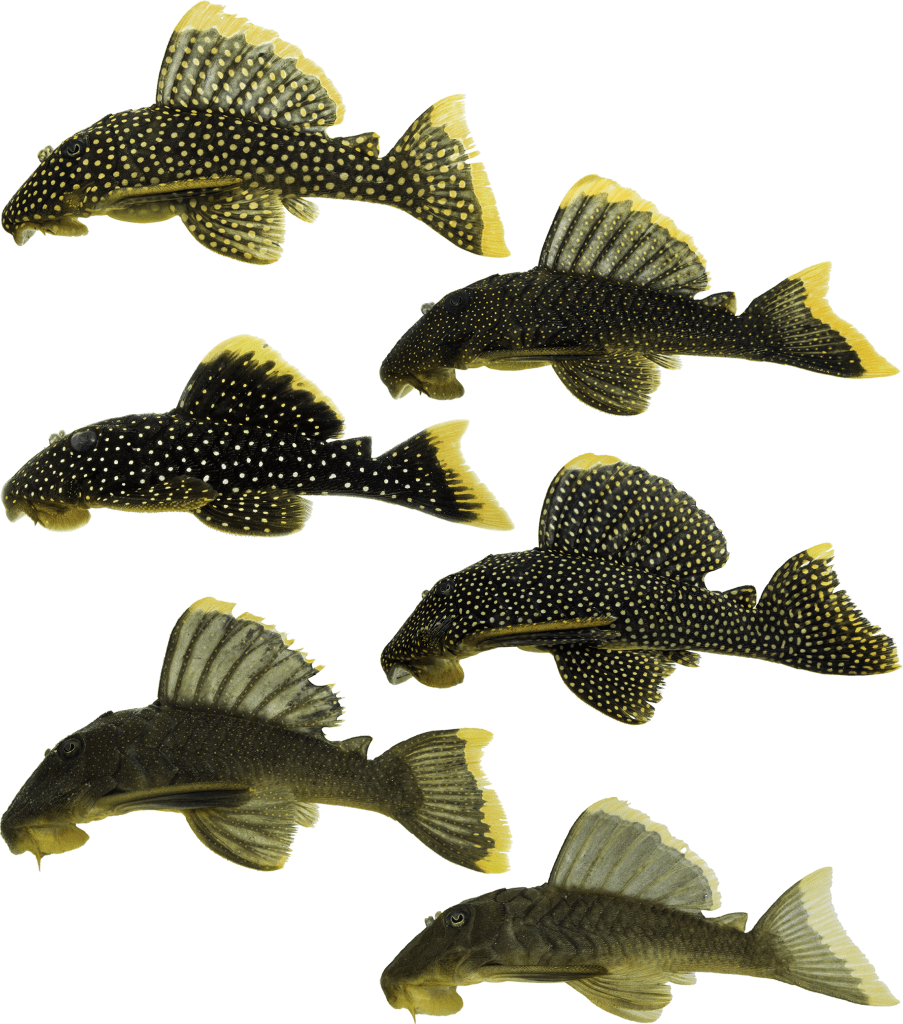

When using this trait be careful with other clades, some such as the Hemiancistrus medians group which includes Hemiancistrus medians, some other Hemiancistrus (this genus requires revision), Panaque, Parancistrus, Baryancistrus and some Spectracanthicus (again another genus that requires revision). In these clades I find females can grow large odontodes seasonally and this was very evident to me in a clearly female Baryancistrus demantoides (Fig 10). The key thing to note about odontodes is they can be shed.

Another clade that easily gets forgotten is Loricariinae, while genital papilla are a clear way to sex many genera within this subfamily. Odontodes can provide an additional quick way to sex many particularly Farlowellini (Farlowella, Sturisoma and Sturisomatichthys mostly; Fig 11). These are reliably hypertrophied around the head and/or rostrum in this clade.

Tentacles

This is an exclusive trait to the genus Ancistrus and the species Lasiancistrus tentaculatus. These are fleshy growths derived from the odontode sheaths (Sabaj et al., 1999), which might explain why sexually dimorphism is shown as related clades such as Lasiancistrus shows some clearer dimorphism in the odontodes. In Ancistrus while in the common bristlenose the males display larger tentacles whereas the females display little to none, there are Ancistrus where females have large tentacles, some which have none and some where the size is the same. Not to be confused with odontodes which is why it is best not to refer to them as spines or bristles.

Some factors that are often myths when it comes to sexing Loricariids

Behaviour

It is a common misconception that males are more aggressive then females and often this has no grounding in experience or science, it’s often an assumption. Males and females do have different territories as males are involved in the brood care whereas females roam but where species are territorial it is in both sexes. In territorial species aggression is shown between and within the sexes. Often this idea of males being more aggressive is based in the coy female myth (Milam, 2013; Rosvall, 2013), many scientists have disproved this but Lucy Cooke makes some good approachable books to the topic. Females in Loricariids have no reason to be less aggressive. Personal experience I’ve seen aggression from both and if anything where females tend to roam their aggression is wider spread then close to the caves where males dwell.

The other myth is that females will not use caves, particularly as juveniles they will definitely hide a lot but even as adults females use caves as refuges, they might even have a preferred cave. Males use the caves to spawn in Hypostominae and some Loricariinae but not all do and those that like crevices will use them.

Conclusion

It can be really tricky to identify whether your Loricariid is male or female. Hopefully this offers some ideas to help sex your fishes. I tend to recommend using the abdomen of the fish as I feel this is most reliable and doesn’t leave space for any amounts of individual variation.

For great comparative photos check out: https://www.suedamerikafans.de/en/zur-unterscheidung-der-geschlechter-klein-bleibender-hypostominaer-harnischwelse/

References:

Lujan, N. K., Meza-Vargas, V., Astudillo-Clavijo, V., Barriga-Salazar, R., & López-Fernández, H. (2015). A multilocus molecular phylogeny for Chaetostoma clade genera and species with a review of Chaetostoma (Siluriformes: Loricariidae) from the Central Andes. Copeia, 103(3), 664-701.

Milam, E. L. (2013). Making males aggressive and females coy: Gender across the animal-human boundary. In Women, Science, and Technology (pp. 206-222). Routledge.

Nirchio, M., Oliveira, C., de Bello Cioffi, M., de Menezes Cavalcante Sassi, F., Valdiviezo, J., Paim, F. G., … & Rossi, A. R. (2023). Occurrence of sex chromosomes in fish of the genus Ancistrus with a new description of multiple sex chromosomes in the Ecuadorian endemic Ancistrus clementinae (Loricariidae). Genes, 14(2), 306.

Oliveira, R. R. D., Feldberg, E., Anjos, M. B. D., & Zuanon, J. (2007). Karyotype characterization and ZZ/ZW sex chromosome heteromorphism in two species of the catfish genus Ancistrus Kner, 1854 (Siluriformes: Loricariidae) from the Amazon basin. Neotropical Ichthyology, 5, 301-306.

Rosvall, K. A. (2013). Proximate perspectives on the evolution of female aggression: good for the gander, good for the goose?. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 368(1631), 20130083.

Sabaj, M. H., Armbruster, J. W., & Page, L. M. (1999). Spawning in Ancistrus (Siluriformes: Loricariidae) with comments on the evolution of snout tentacles as a novel reproductive strategy: larval mimicry. Ichthyological Exploration of Freshwaters, 10(3), 217-229.

Sassi, F. D. M. C., Deon, G. A., Sember, A., Liehr, T., Oyakawa, O. T., Moreira Filho, O., … & Cioffi, M. D. B. (2023). Turnover of multiple sex chromosomes in Harttia catfish (Siluriformes, Loricariidae): a glimpse from whole chromosome painting. Frontiers in Genetics, 14, 1226222.