Men are from Mars and Women are from Venus, Mars the roman god of war and Venus the Roman goddess of love and fertility. Males of a species are often associated with aggression and self determination; females associated with passivity and a peaceful nature. Species such as the Spotted Hyena (Crocuta crocuta) that so obviously turn this view upside down are often of curiosity.

Misconceptions of female aggression are common throughout all vertebrates for various reasons. Within horses one mare determines where the rest of the group are going and the others can determine if to tolerate the male or not. They show a range of different aggressive behaviours between each other and towards males (Curry et al., 2007), hierarchy is as important in the females in a group as it is for males. It’s not all about reproduction but social positioning can effect a females chance as it does for males.

Cichlid Aggression

Cichlids are well known for aggression, perhaps it is a bit overemphasized as their behaviour is much more complex then just needless aggression. It is also a vast grouping where levels of aggression and territoriality vary along with the reasons for. And like Loricariids there are social species and more solitary species, juveniles of any will spend a considerable amount of time in a gregarious state (Forsatkar et al., 2016).

Territoriality is common in cichlids where both males and females defend a space particularly if spawning. In species with large size disparity the females contribution might be easily forgotten yet keep a female alone regardless of the presence of eggs and it is notable she is not a passive individual. In hareming species such as many Apistogramma or the shelldwelling Neolamprologous males hold a larger territory. The females are not shoaling passively, they each hold their own territory within the males defending from other females and sometimes keeping the male within a reasonable distance should there be fry and eggs. Interestingly males play a role in mediating aggression between females (Walter & Trillmich, 1994), this is a role I have seen in other animals where the mixture of sexes reduces overall aggression.

The Siamese Fighting Fish, Betta splendens

This species has been the objects of fascination for many for the males beautiful morphology and their territorial behaviour. While the males have often been the highly valued fishes, females are seen as a side addition. Neither sex is social in the wild, these are largely solitary, territorial fishes so the benefit of keeping females in a group is only that of the owners. Females are shown to be equally as aggressive as males with similar aggressive behaviours (Braddock & Braddock, 1955). Where females are not known for aggression likely stems from the majority of these being plakat, short finned whereas many males are long finned and therefore will struggle with any territorial interactions.

Although it could be argued in a sufficiently big enough tank multiple individuals of both sexes could provide social enrichment assuming they can all develop their own territory. I would largely only advice keeping individuals alone unless spawning, there are social species of Betta that might be a better option for some.

I have worked with and kept a lot of Betta splendens, they are a staple of the aquarium trade and if anything can be a problem is sorority setups. Due to the amount of tanks needed to store individuals only males and the most fancy females could be housed alone. In these sorority tanks there was always a high rate of injuries between individuals, some variants were worse then others, particularly long finned females. In store setups it’s quite easy to experiment and increasing the amount of decor or adding in a variety of different tankmates did not reduce these aggressive interactions.

Why might females display aggression?

- Sociality, even a gregarious species will have many complex interactions between individuals. Maintaining ones place within a shoal hierarchy is a common cause for aggression.

- Territoriality, maintaining a space in which might contain resources such as food or the best spawning caves. Aggression to defend an item of food is common because this will aid in them maintaining a good condition.

- Reproduction, sometimes females will defend the offspring from other species, individuals or even the male.

Loricariid (pleco) aggression

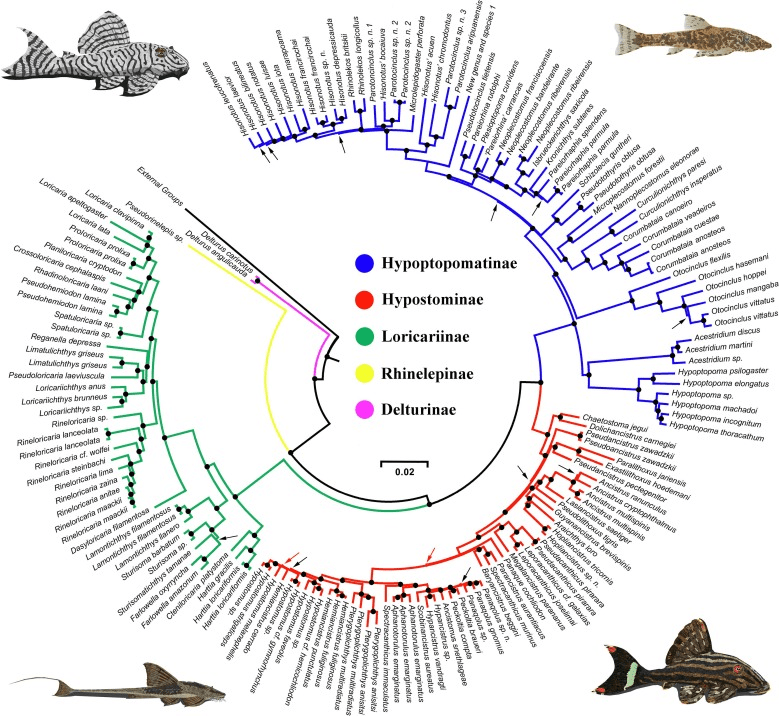

Loricariidae is a 1,051 species strong family of fishes so they cannot easily be generalised. There are both gregarious and territorial species within this gigantic clade. Generally Hypoptopominae are social and gregarious, Rinelepinae I have not heard of aggression from this strange subfamily. Deluturinae and Lithogeninae are subfamilies which never reach the aquarium trade so easily can be ignored here. This leaves the two largest subfamilies, Loricariinae and Hypostominae.

Loricariinae (Whiptail catfishes), the majority of these are social such as Farlowella (twig catfish), Sturisomatichthys (royal whiptail), even those which are not the steryotypical pleco/Loricariid like Rineloricariae. Although some species like Planiloricaria cryptodon can be particularly aggressive, it’s not entirely clear why, these are a species that spawns using their amazing barbels so not need to defend a spot. It is not sex specific but in caring for them around maturity they really need a larger tank or one per a tank.

Hypostominae, the largest subfamily with over 500 species. The majority of fishkeepers keep juvenile and with their illusive behaviour many interactions are easily missed. There is only a small number of gregarious species in this subfamily who lack any territorial tendencies e.g. Ancistrus ranunculus. Hypostominae are far from peaceful in general, sometimes fearsely defending an area from congeners (Hossain et al., 2018).

Hypostominae are crevice spawners in which a male defends a cave when there are fry or eggs within the space (Secutti, S., & Trajano, 2009). Although this doesn’t mean females do not express any aggression, both are territorial and will defend their space from any similarly shaped and sized fishes. It’s not difficult to understand why, as these fishes are likely defending food resources and the best caves to hide from predators regardless if used for spawning. The best grazing spots for many species are probably quite highly prized. Females are only spawning for short periods of time as play no role in brood care (Mendes et al., 2018), but as a result unlike males they tend to roam much larger areas, regarding aggression this poses a larger issue to the fishkeeper.

Some genera display much higher levels of aggression then others, the Acanthicus clade is particularly noted for aggression even in juveniles Pseudacanthicus will rasp on each other. Hypostominae are not loyal with their pairs although fishkeepers have noted aggression towards other fishes of both individuals in a pair preventing other fishes being added. I myself have quite a few mature Baryancistrus, in which the females I’ve seen lunge at other fishes, ram others into caves and intense shoving matches. In the common bristlenose, an Ancistrus, two mature females where this shoving match resulted in serious injuries. I have worked with an adult female Hypostomus luteus who couldn’t be housed with any other fishes within the restricted space of an aquarium after chasing many Pterygoplichthys non-stop.

Aggression is not restricted to males and for many species they are not easy to sex so for the majority of fishkeepers they would not know whether this fish is male or female. They are fishes who enjoy having their own space so plenty of caves and the space needed, it doesn’t mean multiple species can’t be kept together it just means consideration is needed. Aggression is also not limited to being intrasexual as individuals of different sexes will also display aggressive behaviours when not spawning.

The issue with Loricariidae is outside their phylogenetics and taxonomy we don’t know an awful lot about them so there is little research into their behaviour and the causes of territoriality between the two sexes.

Conclusion

Aggression is found throughout many clades of fishes and there are many different triggers for this behaviour. Where a male is aggressive it’s likely the females will be too and sometimes much more then those males.

References:

Braddock, J. C., & Braddock, Z. I. (1955). Aggressive behavior among females of the Siamese fighting fish, Betta splendens. Physiological Zoology, 28(2), 152-172.

Curry, M. R., Eady, P. E., & Mills, D. S. (2007). Reflections on mare behavior: Social and sexual perspectives. Journal of veterinary behavior, 2(5), 149-157.

Forsatkar, M. N., Nematollahi, M. A., & Bisazza, A. (2016). Quantity discrimination in parental fish: female convict cichlid discriminate fry shoals of different sizes. Animal cognition, 19, 959-964.

Hossain, M. Y., Vadas Jr, R. L., Ruiz-Carus, R., & Galib, S. M. (2018). Amazon sailfin catfish Pterygoplichthys pardalis (Loricariidae) in Bangladesh: a critical review of its invasive threat to native and endemic aquatic species. Fishes, 3(1), 14.

Mendes, Y. A., Lee, J. T., Viana, I. K., Rocha, R. M., & Ferreira, M. A. (2018). Reproductive biology of the tiger pleco Panaqolus tankei (Loricariidae) in a lentic system of the Amazon Basin. Journal of Fish Biology, 93(4), 711-714.

Secutti, S., & Trajano, E. (2009). Reproductive behavior, development and eye regression in the cave armored catfish, Ancistrus cryptophthalmus Reis, 1987 (Siluriformes: Loricariidae), breed in laboratory. Neotropical Ichthyology, 7, 479-490.

Walter, B., & Trillmich, F. (1994). Female aggression and male peace-keeping in a cichlid fish harem: conflict between and within the sexes in Lamprologus ocellatus. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology, 34, 105-112.